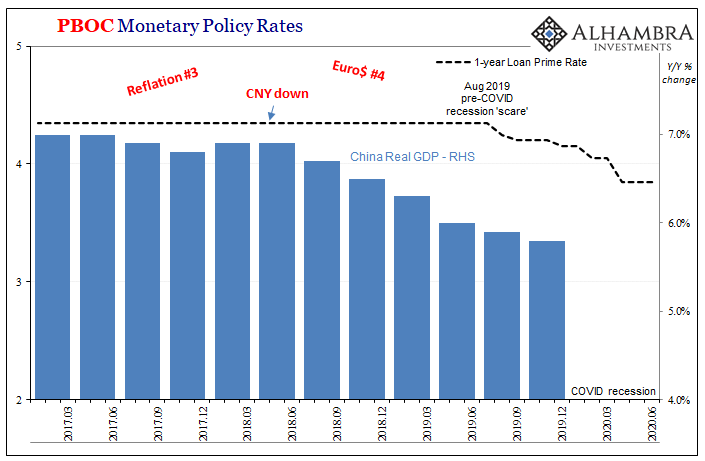

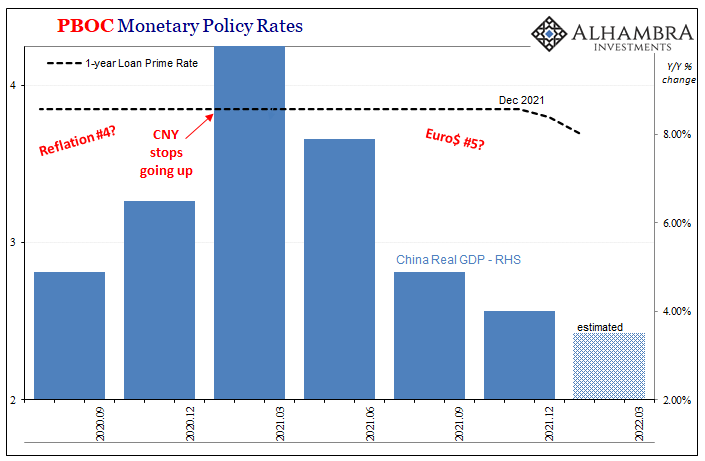

Chinese authorities responded to their faltering economy in 2018 by diverging from their Western counterparts. Their PBOC would lean into rate cuts (RRR) at the very same time America’s Federal Reserve would accelerate more in the direction of rate hikes. The ECB, for Europe’s part, intended to follow the Fed’s path, reaching December 2018 and terminating its own QE with rate hikes expected soon thereafter.

Many had come to conclude the US was winning, or had even won, the “trade wars.” President Trump had provoked them in part to keep his main campaign promise of doing something from the Rust Belt denizens who supplied Candidate Trump his final thin margin of victory. Why not go after China, politically speaking?

During the first part of the “conflict”, it seemed to be going exactly to plan. The Chinese economy stumbled right at the start of 2018, a severe misstep that was completely misdiagnosed. As would be the coincident weakening conditions over here once slowly but determinedly the same (macro) rug out was yanked out from under Jay Powell’s hawkish talons, too.

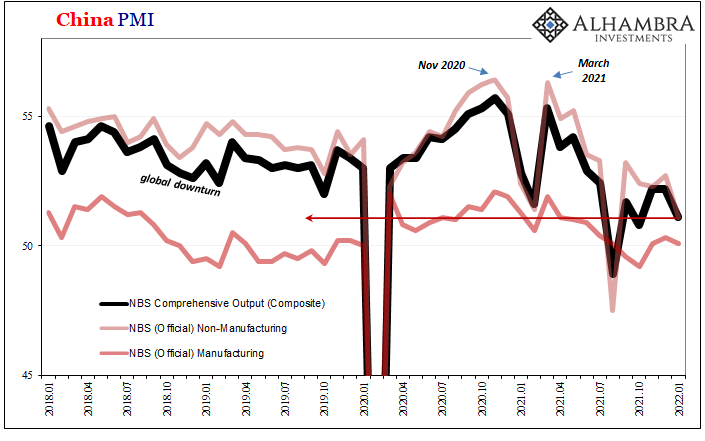

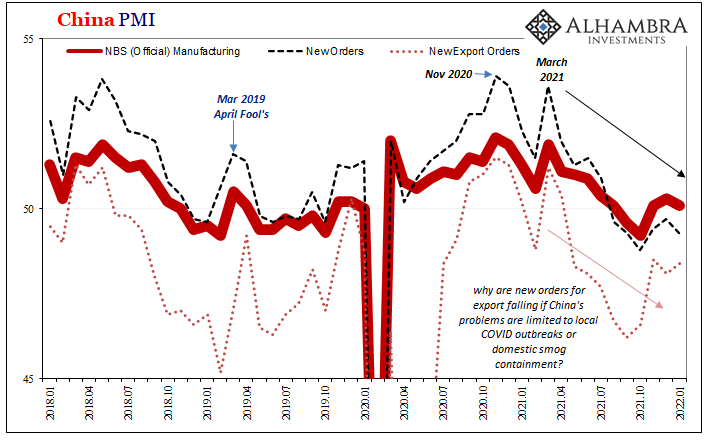

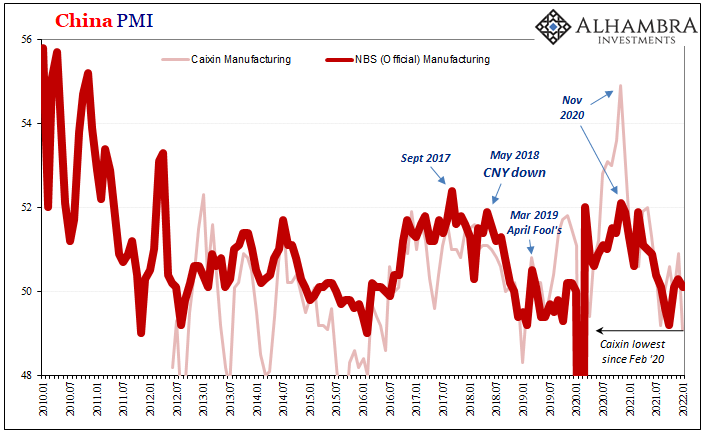

By early in 2019, however, there appeared a sliver of hope how China was being reinvigorated by any of the 2018 monetary policy “accommodations.” Fittingly, on April Fool’s Day 2019, China’s NBS reported a rebound in its sentiment indicators; the “official” PMIs for services (non-manufacturing) and industry (manufacturing).

The latter has proved to be a relatively reliable indicator not strictly for the Chinese economy, rather as a proxy for the global system since so much of it – at the margins – flows into then out of China’s vast manufacturing sector. When this is robust, it’s not because of the PBOC.

According to government’s figures, the latter PMI, manufacturing, had fallen all the way down to 49.2 for the month of February 2019. This highlighted the economy’s pain only presumed to be a matter of those “trade wars.” The new April Fool’s number for the following month of March rebounded nicely to 50.5.

It was heralded widely as the expected beginning of a turnaround, the lagged effective therefore optimistic response to the prior year’s skilled implementation of “stimulus.” Wall Street analysis were generally very pleased:

“We believe policymakers will stick to their commitment on policy easing to stabilize growth,” the BofA Merrill Lynch analysts said in a note to clients.

Chinese policymakers were committed to their policy, sure, that just didn’t mean it was an effective one or set of policies. The NBS manufacturing index would immediately fall right back to 50.1 for the month of April before then sinking back below fifty the very next month of May.

And so it went from there, with the PBOC by August 2019 also cutting the LPR rate, too. The one-month reprieve for March 2019 quickly forgotten as China’s faltering economy faltered even more.

Shocking the West, however, with mainstream Economists and central bankers routinely having cited “trade wars” for the Chinese weakness soon found their own backyard fallen into the same category. As you know, and I’ll keep reminding you, the ECB never got to rate hikes and instead would end up restarting QE by early September 2019.

The Federal Reserve was already one rate cut in by that point, with a second in the same month concurrent to the massive repo rumble which to this day has never been adequately explained. As it would turn out, the Chinese troubles were broader than previously thought.

China’s deepening economic woes were neither “trade wars” nor specifically related to China. Not only would this prove to be the case throughout 2019 pre-COVID, it had already been especially back in 2011 and 2012, a repeating pattern as I had discussed here.

But we have to consider that China’s problems aren’t of its own making, and that the PBOC’s actions which have been called stimulus and easing ever since being unleashed just about a year ago have failed in every way to account. The first RRR cuts took place all the way back in April 2018, and they didn’t seem very (or at all) effective in keeping the Chinese economy from getting into this mess in the first place.

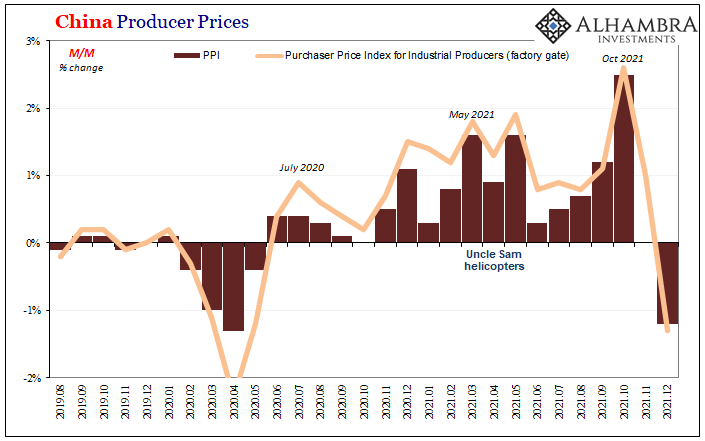

RRR cuts began last year already, with a second dose to end 2021 combined with one rate cut to the LPR (which last time wouldn’t be reduced until August 2019, for reference) duplicated again earlier this month. The monetary “accommodation” in China doesn’t seem to want to ever accommodate much other than Western confidence.

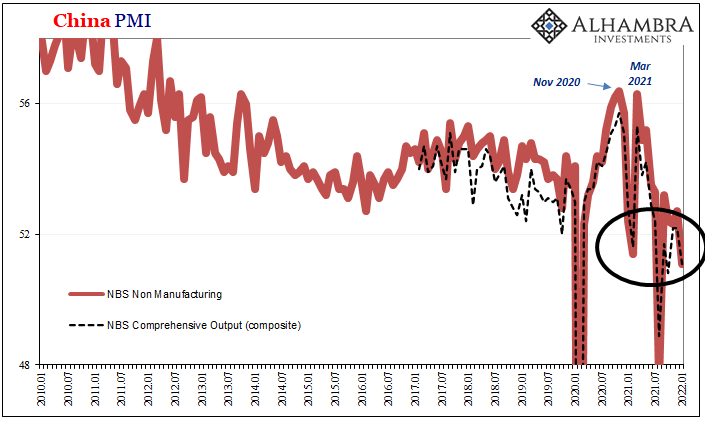

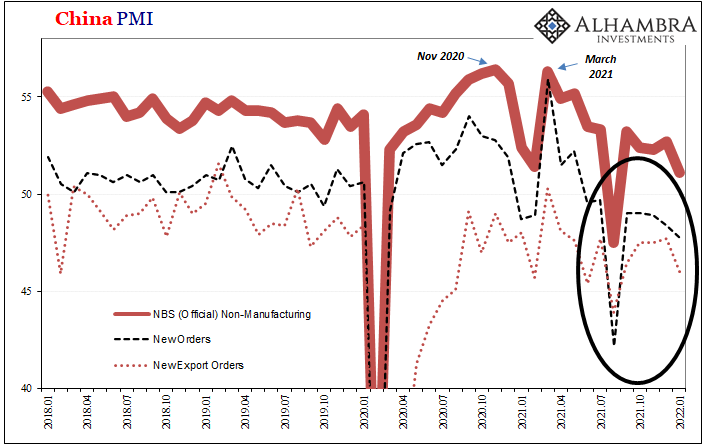

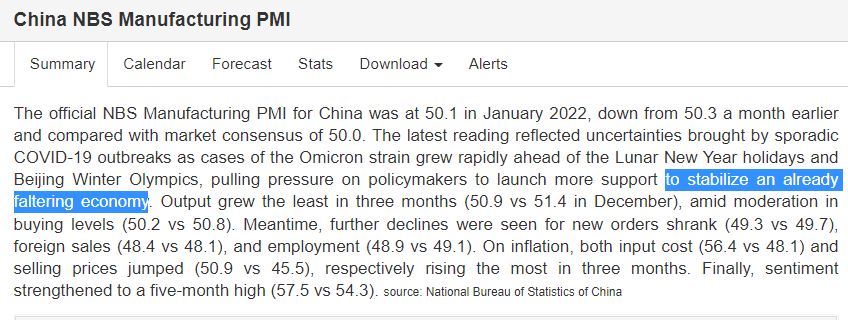

To that end, the latest PMI estimates from China, released late last night, again the same. December’s small rebound was described as the first step toward success from those policies. The difference this time is, of course, no longer “trade wars” as the primary excuse when it doesn’t work out.

All the major sentiment numbers disappointed expectations as they resumed the downside, blamed on omicron. The NBS Manufacturing dropped back to 50.1 for January 2022 from 50.3 in December, which had been up from 50.1 in November; the NBS Non-manufacturing declined all the way to 51.1, one of the worst results in the series, from 52.7; the NBS composite, or Comprehensive Output, likewise among the worst at the same 51.1. Each of those two had temporarily, it seems, rebounded in December.

Importantly, new orders were contracting, below 50, in both PMI datasets.

Even Caixin’s Manufacturing PMI severely underperformed, and even if generally more noisy than its official counterpart, falling to just 49.1 this month (from 50.9) is its lowest since February 2020.

Is the Chinese policy of zero-COVID really the problem here? Since the Fed has gone ultra-hawkish, even more than 2018, we’re led to believe that any faltering of the Chinese economy must be due to some China-specific issue. Being on the wrong end of trade wars sounded plausible enough back when, and it might again today with the reported pursuit of the most draconian pandemic measures.

Yet, even as these factors are cited this way, there’s also the increasingly undeniable unease maybe there really is more to it. If so, it sure wouldn’t be the first time.

Stay In Touch