It was likely inevitable, broad economic commentary sifting into the laundry yet again. With alarming regularity, every couple of years the idea and the term “decoupling” rears its filthy head as major global economies seem to diverge. They don’t, though, merely an illusion, a trick due mostly to differences in timing.

It was Mohamed El-Erian of PIMCO all the way back in 2010 who is credited with popularizing the slang.

At some point, when you only have dirty shirts in your closet, it’s about your cleanest dirty shirt. The U.S. is your cleanest dirty shirt.

Back then, Europe was on its way into quick re-recession while Japan was barely off its Great “Recession” bottom. By way of direct comparison, the US was hardly thriving but wasn’t nearly as bad off as those others. The least rotten apple in a spoiled bunch still may not be edible.

The pattern merely repeated a few years later. Japan (along with China) struggled mightily in 2014 (despite the massive, “game changer” QQE) while Europe never really got going even after exiting that 2012 contraction. By late in the year, though somewhat dingy, many thought the US economy represented an even brighter comparison than before.

Janet Yellen’s Fed clearly believed so, ending QEs 3 and 4 while planning to quickly pivot into rate hikes to head off the inflation pressures she presumed were the most likely threats to America’s forthcoming “recovery.” She should have paid closer attention to the laundry, as I had advised right as the QEs were terminated, way back in October 2014:

The persistent talk of the “cleanest dirty shirt” is perhaps the biggest violation of the interconnected nature of all of this. In 2008, the rest of the world was supposed to “decouple” from US weakness in a sort of reverse situation, yet there was no such separation in economy or finance.

The 2008 experience really should’ve buried “decoupling” for good, instead its variables merely switched with the American shirt since claimed as the cleanest.

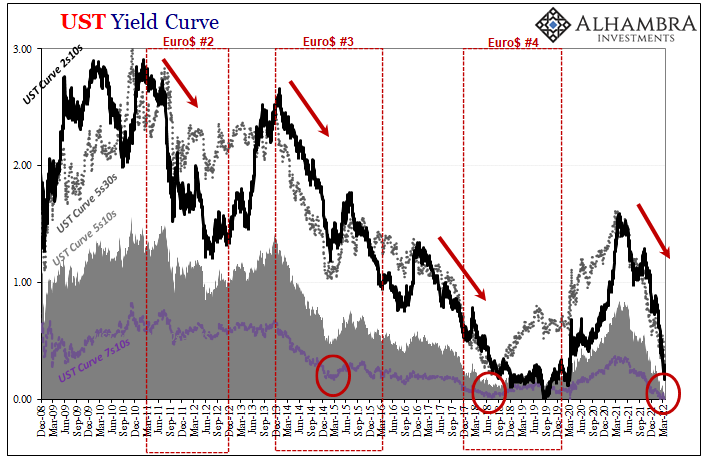

For Yellen’s Fed heading headlong toward her anticipated mid-2015 rate liftoff, the last few months of 2014 were, shall we say, confusing. Despite the so-called best jobs market in decades, monetary, financial, and economic warnings spread far and wide. Focused on the unemployment rate near exclusively, policymakers steadfastly ignored curves providing in-depth real-time narration of a situation going awry globally.

The issue wasn’t decoupling, rather when the downturn would eventually synchronize.

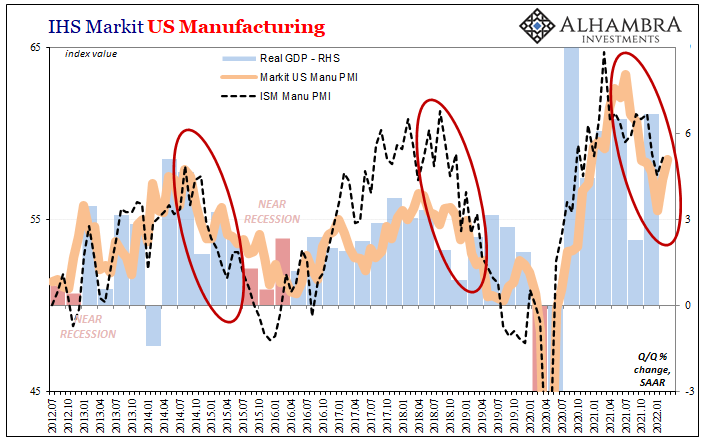

The high frequency data was not without its usual volatility, which if you get lost in the statistical noise you can easily lose your bearings. For example, Markit’s US Composite PMI – a pretty solid proxy for US real GDP – dropped 5.5 points over the final three months of that year, around the same time when the “dirtier” of the global stock of macro shirts showed up at the laundry “somehow” even more stained than ever.

Markit’s index, however, quickly rebounded during the next three months, the first quarter of 2015, gaining back all 5.5 plus 0.3 more, reaching its highest in nearly a year (circled on the first chart above). With all the rest of everyone’s blouses deeply soiled, Yellen’s group really did come to believe ours wasn’t, therefore she’d remain on track for her looming inflation fight.

Yet, it was during those same months when all the prior year’s financial and monetary noises came home to roost as of more serious varieties of trouble. As discussed just yesterday, a key Treasury yield curve node, the 7s10s calendar spread, flattened out to some of its lowest going back to 2007 (the first circle on the chart immediately above).

Two thousand fifteen did not go as Yellen had planned, but would for anyone who made theirs from the curves. America hadn’t ever been the cleanest dirty shirt, it was instead just a laggard behind the leading tide of global weakness which spread from Asia first; near recession by the end of the year rather than full-blown recovery justifying Yellen’s rate hikes (plural) which, therefore, never happened.

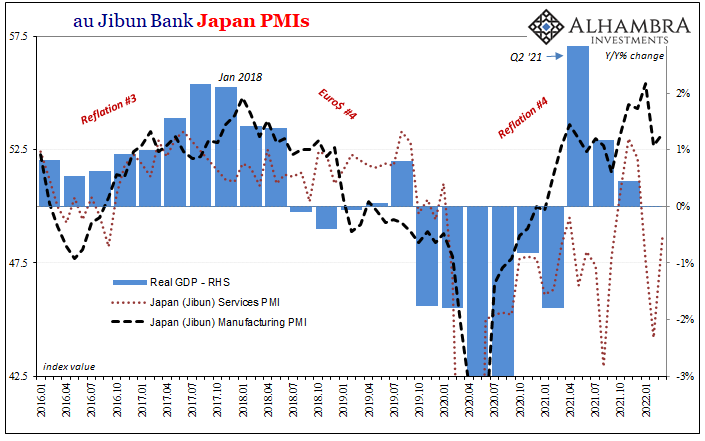

Decoupling was brought back in 2018 because no one ever pays attention; the US may have begun that year with fewer questions than either Europe or Japan, by 2019 there wasn’t really any difference left between any of them. Euro$ #4 came for everyone eventually then, too.

Again, a viewpoint grounded in the curves (7s10s very nearly inverted in May and June 2018, also circled above) helped you avoid the unhelpful laundromat analogies.

In 2022, yep, it’s coming back. And the dirty shirt has some numbers behind it this time, as well. Sticking with IHS Markit’s US Composite, after giving up 6.5 points October 2021 to January, blamed on omicron, it’s right back up and even higher (best since last July) as of the flash reading for March 2022.

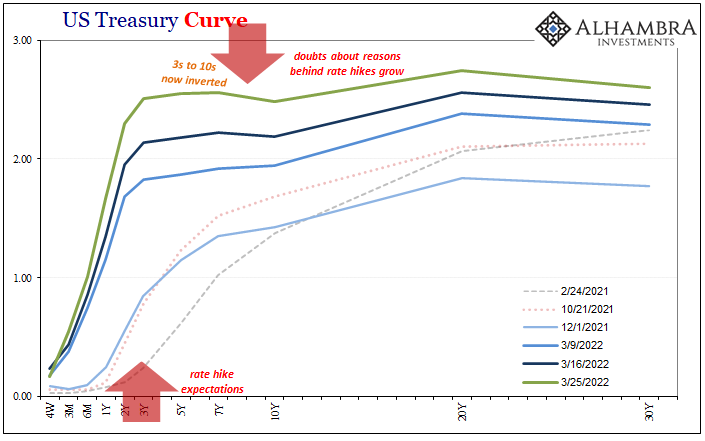

Yet, as I write this, the US Treasury 7s10s calendar spread isn’t just seriously low like 2015 or nearly flat as in 2018, it is bigtime upside-down to the tune of -8 bps!

While US sentiment numbers are up somewhat from the start of the year (manufacturing, too), elsewhere around the world they are not. Markit’s March flash for Europe came in at 54.5, down from February’s (final) 55.5.

The figure for manufacturing sentiment fell to 57.0, which sounds pretty solid, yet was the lowest in 14 months due to a slower output reading but mostly a clear slump in new orders (nearest to 50 since July 2020) and new export orders dropping under 50.

All these are being blamed, as you’ve already guessed, on Russians.

Over in Japan, if we’re to believe the COVID-effect, that economy is apparently still struggling with delta corona, if not the original variant. Unlike everywhere else, even China, the Japanese despite some of the least restrictive government overreactions to the pandemic, judging by their economic results you’d have thought those were the opposite.

To begin 2022, services is suffering all the same and the minor late-year bump in manufacturing sentiment already appears to have waned. Like Europe, the direction for Japan already isn’t good.

If there seems to be a key difference this time checking the laundry compared to those prior dirty shirt inspections, it’s that 2021 didn’t really get going all the much in the first place before meeting up with its possibly inevitable reverse (“growth scare”). Though US estimates are again among the better, market positioning indicates another instance of pure timing.

After all, a global economy that never really recovered from the last recession isn’t really going to be much for resisting high prices foisted onto it; the same prices which made last year seem like it was better than it actually had been.

Maybe all these together account for why curves are so much more twisted and resistant to rate hikes, threats of rate hikes, and more promises of persistent inflationary threats. There are no shirts, there is no laundry, everyone and everything they’re wearing is all covered in the same dirt.

Stay In Touch