The price illusion. It is causing enormous confusion and difficulty, making the global economy out to be something it really isn’t. In fact, the whole situation is being viewed backward. What’s presumed from this is a red-hot economy causing consumer prices to skyrocket.

In such a scenario, central banks might need to rush their rate hikes to cool it down (assuming, of course, that’s what modern “central banks” actually do). They’d have to step it up because red-hot growth would otherwise keep going and so would the alleged inflationary spiral.

But that isn’t what has happened. On the contrary, an outward shift in demand (for various reasons, some different in different places around the world) combined with inelasticity in supply (including the ability to move and deliver goods) caused prices to rise which then created the nominal picture of a scorching economic recovery.

Everything is reported to be backward, and now upside down (markets).

The illusion became much clearer over the last half of last year, yet the belief in it remains steadfast anyway. One key reason why is central bankers, at least those here in America who can’t help themselves but to constantly race to pledge their hawkish virtues higher by every passing week; or by day, sometimes.

Others, particularly the non-US pair among the trio of bears in the macro Goldilocks story, the ECB and PBOC, have instead been less prone to such mass hysteria (psychosis) for whatever reasons. Those might even include a rational, far less inflated (pun intended) take on the global situation.

This one’s even more compelling if not weird because European consumer prices accelerated to 7.5% year-over-year (preliminary) for March 2022, which, you’ll note, is practically the same pace for US prices. However, unlike the Powell panic, Christine Lagarde’s ECB continues to play it rather cool.

The ECB won’t raise rates until after QE is finished and that is still months away, and even when it is the rate hikes might not begin right then. Further, Lagarde has stated they’re to be “gradual” once (if) started.

Such a clear distinction ECB from Fed. With consumer prices in both places up around the same levels, what is the difference? It could be that each economy is facing different factors (spoiler: no), though it’s far more likely the variance really just central bankers.

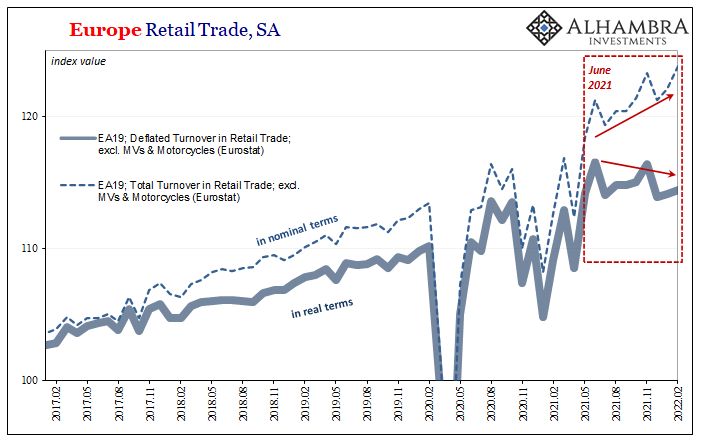

In Europe, the price illusion is really noticeable (though it also is in the US). Total retail trade in Europe’s group of 19, according to Eurostat, has exhibited its COVID-panic ups and downs but the official caution rather than the purported heat is all the second half of 2021 right on into the first two months of 2022 (latest data, released yesterday, for February).

The estimates show a serious and growing discrepancy between nominal and real. That’s not an overheated economy, it is consumers who have for months been paying more and getting less. Demand destruction comes about once paying more to get less means paying more for necessities while cutting back on pretty much everything else.

Nominal retail turnover (sales) is going up as are consumer prices on average, meaning that prices are the cause rather than the effect. Adjusting for them, the estimated volume of consumer trade is declining as if Europe is already on its way toward mild recession and has been for some time. The difference so far as goods are concerned, like America, the buildup of inventory.

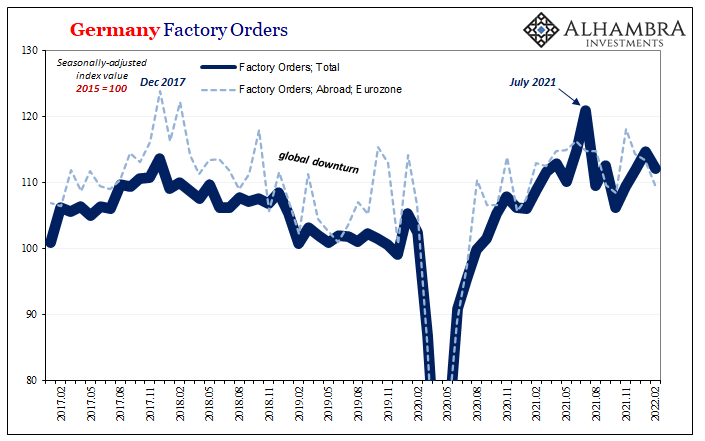

And if consumers are buying less (not counting motor vehicles sales, meaning this isn’t semiconductors) as inventories accumulate, then no wonder European producers are since producing slowly while retailers and wholesalers cut back on orders, too. Classic inventory cycle at the leading edges of demand destruction.

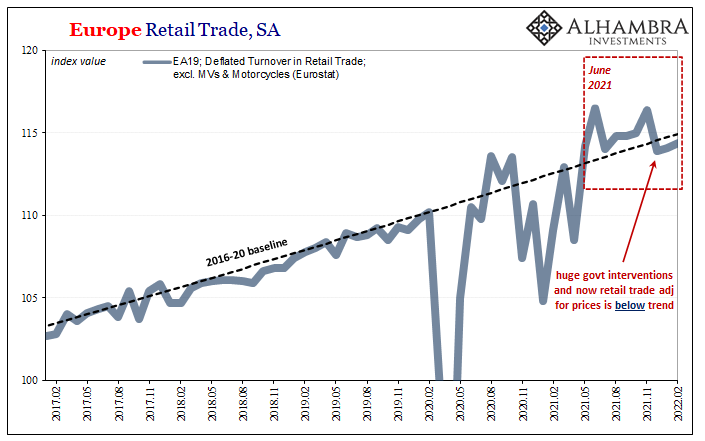

It’s only nominal terms where the economy looks so much the better. For the whole group of 19, despite massive government intervention the level of real retail trade has now fallen behind the pre-2020 baseline (above) which really wasn’t all that great.

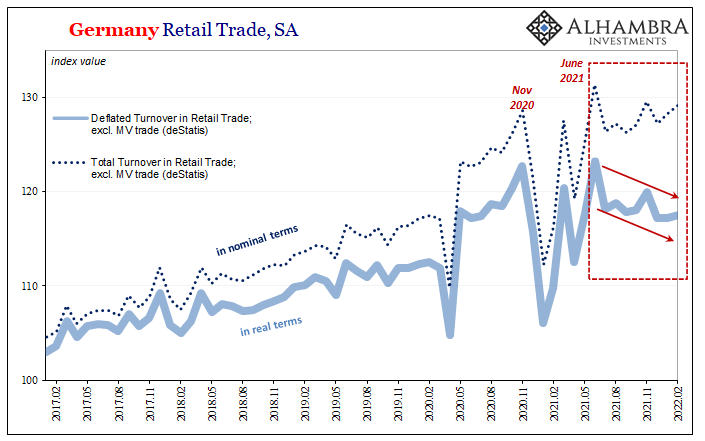

In just Germany alone, for example, total retail trade even in nominal terms has been declining since last June. Thus, German factories which should be running actually hot have been cooling off (and then factor softening, lower orders from other countries in Europe as well as further abroad) all the while the inflation goes pretty much unchallenged worldwide.

This only raises the question of whether European policymakers are being far more cautious, downright reasonable than their American counterparts. It may just be because in Europe they learned the hard way to be patient and not just jump to inflation conclusions, whereas those at the Fed demonstrate only a repeated resistance to learning anything.

…there is the lesson of 2018 to begin with. Mario Draghi, Lagarde’s immediate predecessor, you might recall his huge error when from the start of that year he dismissed growing weakness (in Europe as well as China) as nothing more than an immaterial slowdown from a rapid high in 2017. It did not work out well for him, or, you know, Europe and the rest of the world.

Rather importantly, it also didn’t go very well at all for one Jay Powell.

It might be that Christine unlike Mario is more attuned to not just that mistake but also how it could’ve been avoided by paying much closer attention to what was going on in China and with the PBOC’s interpretation of risks and tendencies rather than sticking closely by the uncontroversial mainstream-ness of Powell and the Fed.

Notice, too, how in that 2018-19 period of recession in Europe, European consumers didn’t actually participate! That earlier contraction was centered around declining investment along with, or because of, a bigger decline in trade and money which hadn’t had a chance to reach consumers at least before the coronavirus would.

For as bad as it got just around late 2019, entering 2022 the average European is being forced into a situation more like 2012. That has to be a factor in the ECB’s very clear caution in striking contrast to the Fed’s damn-the-torpedoes recklessness. Thus, while Ms. Lagarde might express her confidence in the global economy and Europe with it, her actions, or lack of actions thus far, speak volumes.

Not prices.

Bond prices, though.

Stay In Touch