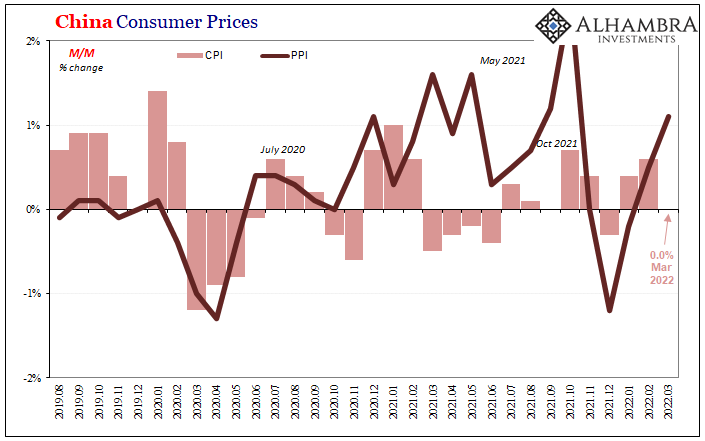

If only the rest of the world could have such problems. Chinese consumer prices were flat from February 2022 to March, even though gasoline and energy costs predictably skyrocketed. According to China’s NBS, gas was up 7.2% month-over-month while diesel costs on average gained 7.8%. Balancing those were the prices for main food staples, especially pork, the latter having declined an rather large 9.3% last month from the month before.

Keeping energy but removing food, China’s CPI would only have gained 0.3% for the month, and just 2.2% year-over-year. With food, the overall consumer price increase was just 1.5% year-over-year.

We should be so lucky.

Wait, strike that.

China’s lack of “inflation” comes at the expense of…something. Many would say it is the coronavirus, or rather the government’s absurd, increasingly unjustified commitment to not having any of the disease anywhere. To the point now the horror stories and accompanying 1984-style videos have managed to filter out from the notoriously censorious country.

But why?

Is this Zero-COVID really about COVID? There are rumors of discord among the upper echelon, more political intrigue by which Emperor Xi might have to flex his multi-faceted internal muscle. Don’t like the direction China’s lackluster economy is taking, too bad because you’ll learn to love it or your entire city doesn’t get to eat (yes, this is slight hyperbole).

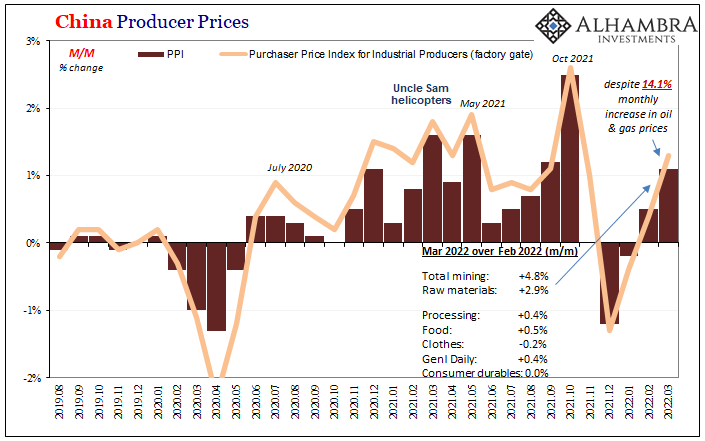

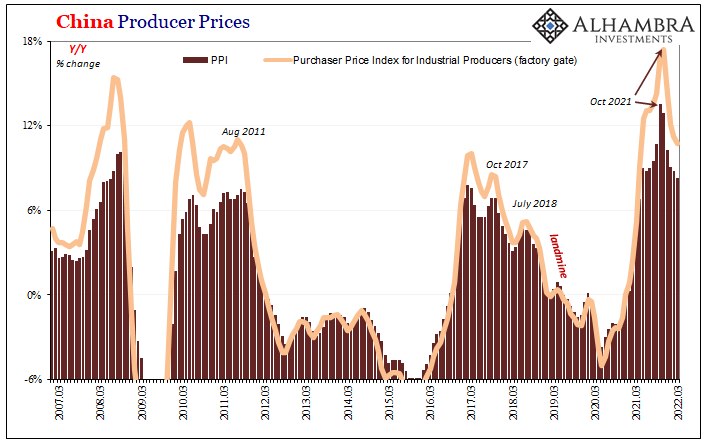

That would seem to be the direction of Chinese prices, both consumer and producer. By that I mean the uninspiring economy leading to the overly sensitive cracking down. In terms of producer prices, the yearly change continues to trend lower despite two months in a row with extremely high contributions from energy.

The NBS said gasoline prices for producers spiked 14% in just March alone, after rising more than 10% during just February. Yet, apart from materials costs and those in other commodities, producer prices have been decelerating and, in many cases, outright declining. It’s just these are overshadowed by the external forces which popped crude the last few months.

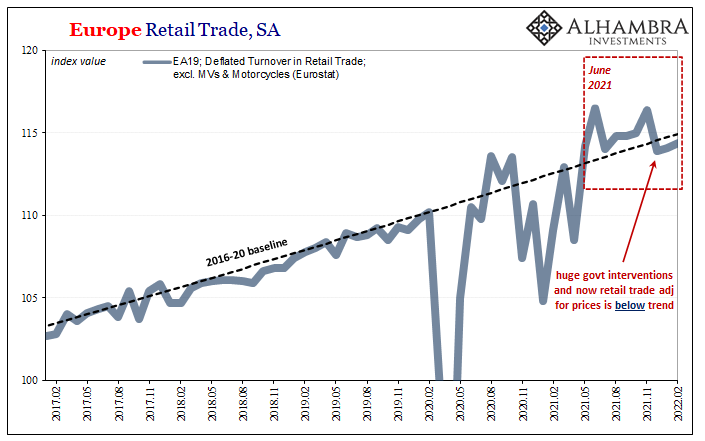

By consumer and non-energy producer prices, there is a big difference China from the US or Europe.

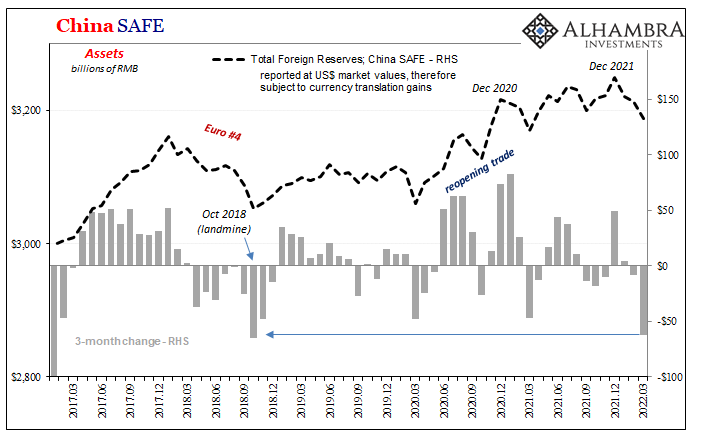

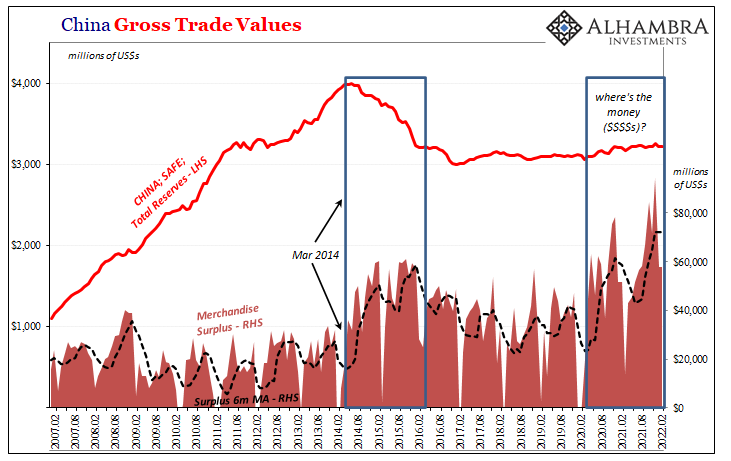

Apart from prices, maybe less of a difference than you might think (particularly with Europe, at the moment). According to China’s SAFE, total foreign reserves declined for the third straight month in March. It’s both the first time that has happened along with the largest cumulative decline in any three-month period since…October 2018.

Obviously not a good comparison.

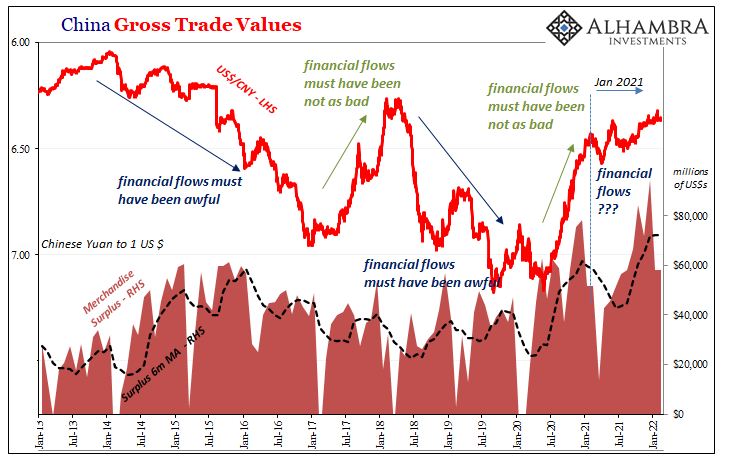

And, of course, there’s no immediate explanation for this. To start with, the Chinese merchandise trade surplus is as gargantuan as ever. For January and February 2022 combined, the latest data until Wednesday’s (US time) update for March 2022, it was another 12% better than January and February 2021. Record surpluses.

So, just where is all the money?

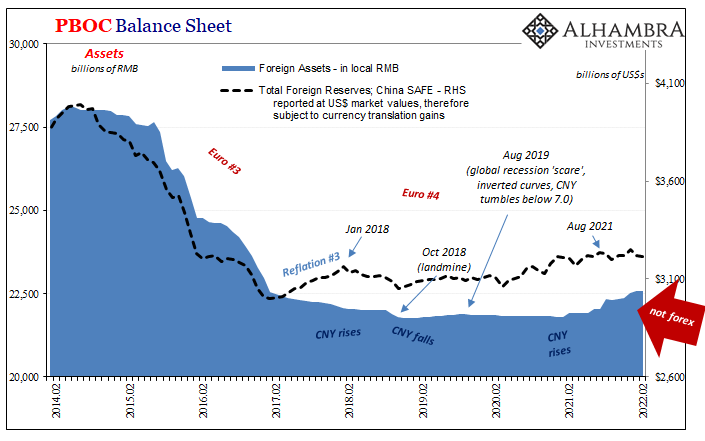

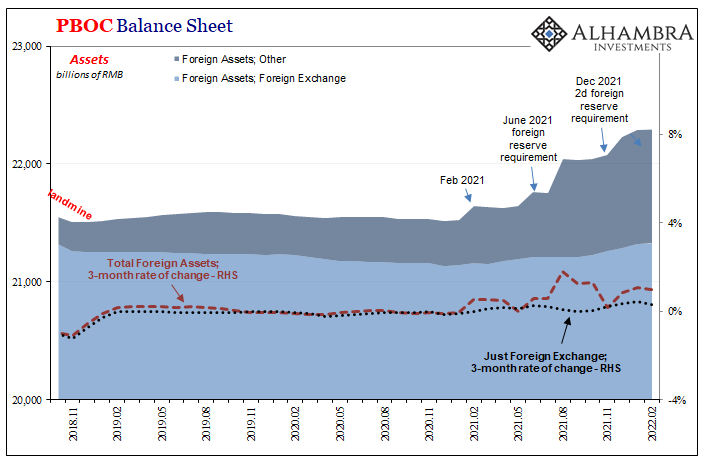

As has been the case suspiciously for years, we won’t find it at China’s central bank, either. The PBOC’s account for foreign reserves, particularly foreign exchange (not including deposits demanded from banks), is a straight-line wasteland of opaque operations for reasons always remaining undisclosed.

We can guess, however, once we put all these clues together, especially since we’ve seen these “conundrums” several times before.

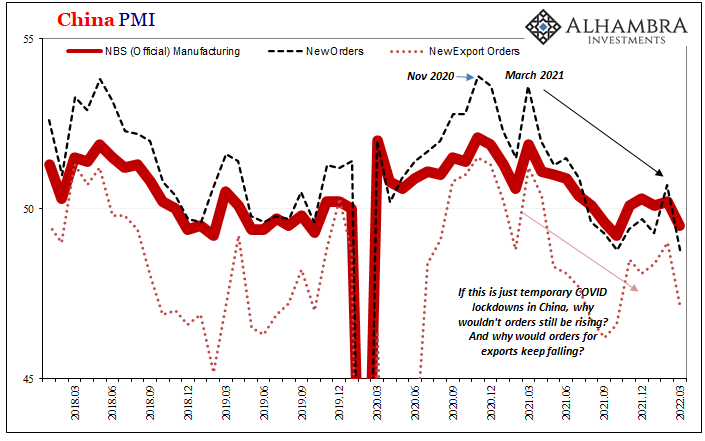

Outside of energy, which has nothing to do with China, there is every reason to suspect that the Chinese began this year with a lot less going for them than has been said. And what’s been said hasn’t exactly been very good, apart from the trade figures. In fact, only trade.

Even looking at the exports and imports, the fact there is no money entering the country – now shrinking even by official account – given the former’s historic surplus tells us that financial flows just might be increasingly negative, too. In other words, the eurodollar market is voting with its figurative feet while it can.

Sluggish and decelerating prices, even in this global supply shock aftermath, combined with increasingly brutal internalized dictatorial methods and even more missing “dollars” than is usual, it adds up to a picture of huge global risks way beyond strictly China or worldwide “inflation.”

Particularly if China’s economic struggles overall have anything whatsoever to do with the rest of the world’s inventory problems.

Twitter wants me to add a comment when none is necessary. https://t.co/aXWnEI0NHp pic.twitter.com/xNRtUBRji2

— Jeffrey P. Snider (@JeffSnider_AIP) April 11, 2022

Stay In Touch