ECB Governor Christine Lagarde surprised, maybe even shocked most people when a few days ago it was reported she’d told her fellow policymakers to keep their mouths shut. Don’t go running to the financial media. Justifying the censorship, Lagarde said it was important for the central bank’s key officials to present a unified front given some drastic challenges over the months ahead.

Most observers took this to mean bottling up dissent from the so-called hawks; that is, those who might both speak German while also vehemently opposed to the measured, perhaps plodding pace plotted out so far by the ECB’s leadership. In sharp contrast with the damn-the-torpedoes Fed, impatience isn’t just perceived competition.

Right on cue, several someones immediately, anonymously blabbed their discontent to Reuters:

“Do you want leaks? Because this is how you get them,” one of the sources, who asked not to be named, said. “If people can’t speak openly, they’ll still talk but using different channels.” The move also surprised many as the ECB devised a new communication strategy just last year after an 18 month review and such restrictions were not debated then.

What will they talk about? It might just be that some would say they’re dissatisfied by the ECB’s “hawkish” position in the first place. If you take away anything from how Lagarde has laid out the policy course, it is a considerable tightrope between the irredeemable inflation-ists in between those who’ve been around the false dawn block a few too many times.

Christine may simply want to avoid whatever negative sentimental effects of too much jawboning as there already has been over here on the US side – to the point that financial curves are inverted, several wildly, alerting the public in a way to potential downside (recession) dangers the ECB would rather go unnoticed.

While the one group of hawks is focused like, well, a hawk on CPIs (or HICPs, as they might be in Europe), the other clique has a growing list of its own concerns that won’t add up, or end up, with inflation.

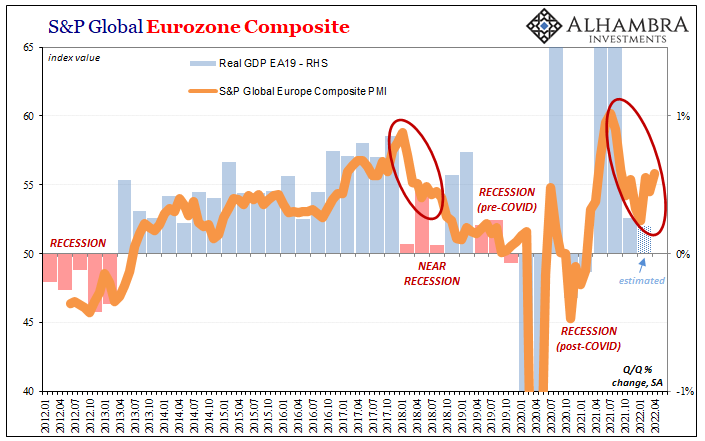

S&P Global (the merged successor to IHS Markit) put out its services, manufacturing, and composite PMIs for Europe and its nations last week. On the one hand, some good news; the services version rose as any last effects of omicron lockdown madness fade further away.

Even with Russia replacing COVID as mainstream worries, on the strength of the services PMI the composite lifted to 55.8, its highest since last September (above).

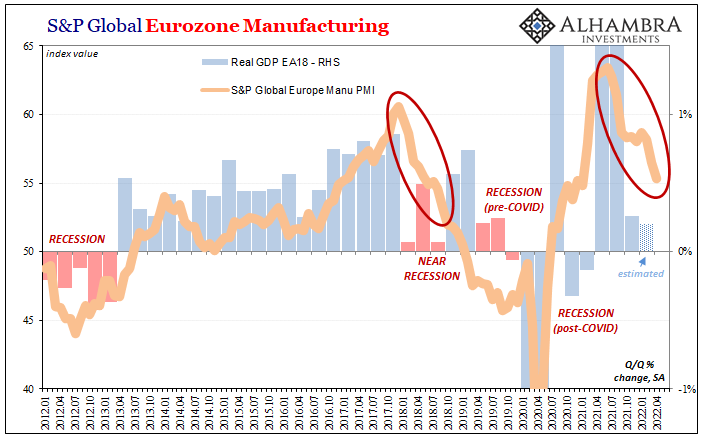

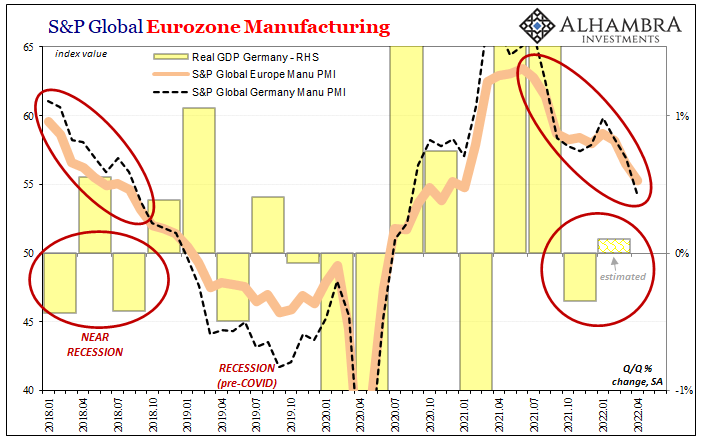

While that sounds good, and the improvement is certainly better than the other, it’s again more about another round of reopening than organic advancement. How do we know? S&P’s manufacturing index:

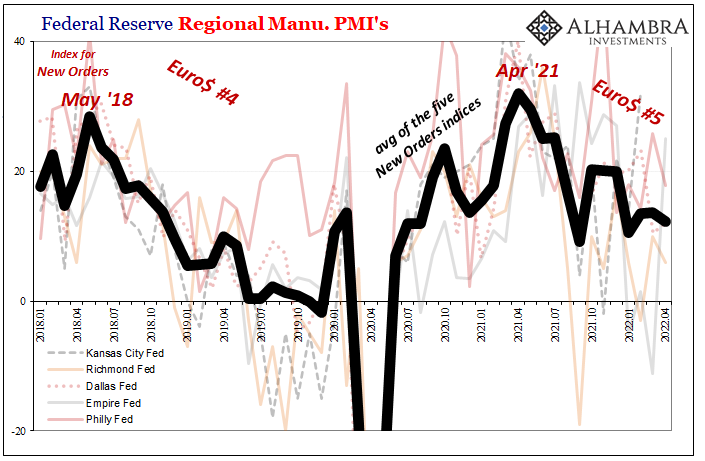

New orders for goods rose at the weakest rate since June 2020, registering only a modest increase. Lost orders were blamed on soaring prices, the cost of living squeeze and signs of increased risk aversion due to the Russia-Ukraine war, as well as the shift of spending to service sector activities. [emphasis added]

The manufacturing side, by contrast, displays only a list of growing concerns rather than growth – beginning with the orders index just straddling 50, more like recession-filled 2020 than inflation-fear 2022.

But, as always, it’s not just one PMI or another. There’s several of those to go along with so much other data.

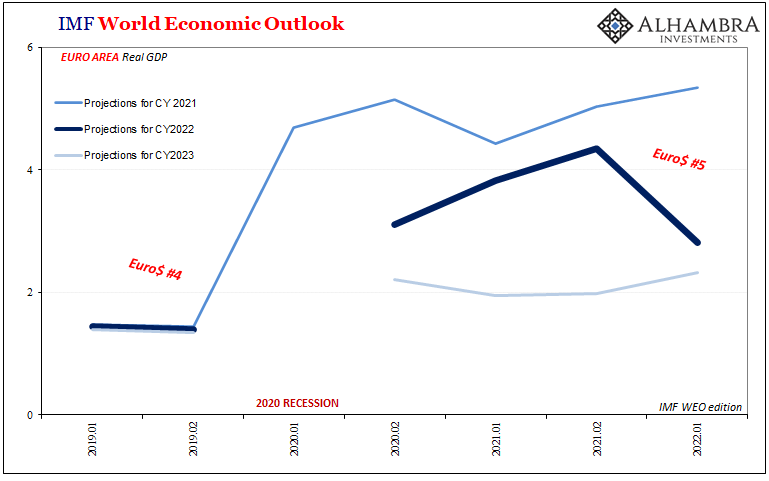

Take European GDP, for example. Eurostat will compute and release its Q1 2022 estimates on Friday. According to most expectations (FWIW), nobody is expecting much (blamed on everything from Ukraine to oil to the Fed screwing with the everyone’s mind), just 0.2% to 0.3% quarter-over-quarter.

Anything close to that and, as you can plainly see above, this would leave an entire six-month period across Europe with very little to show for it. That’s half a year with manufacturing – the one global bright spot – seriously decelerating while European GDP drops to at best a complete standstill.

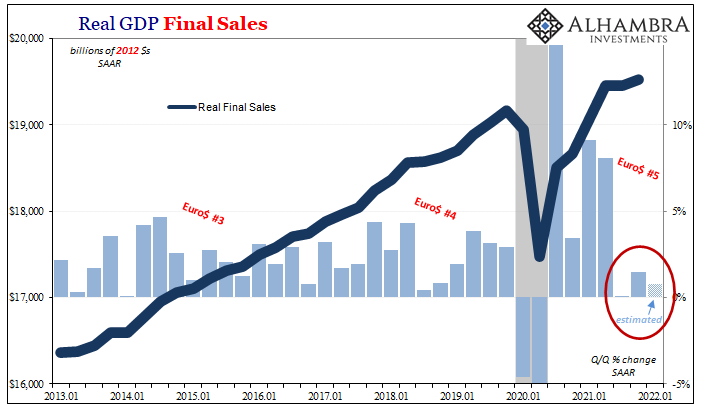

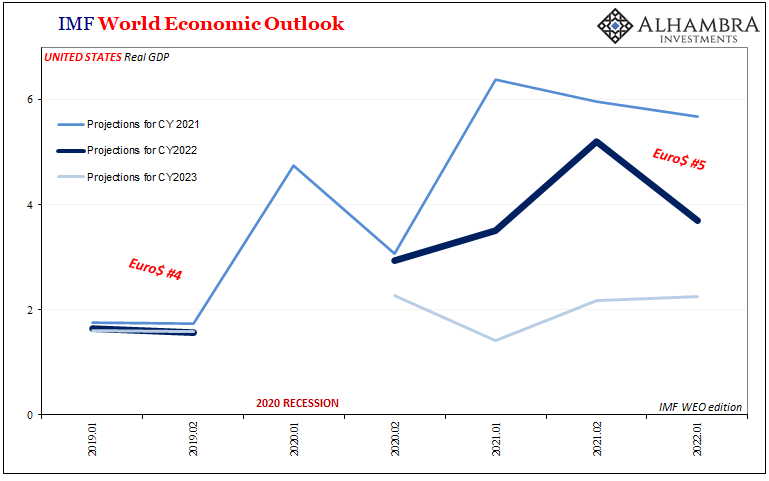

US GDP estimates are likely to come out even worse; as in, the American Bureau of Economic Analysis had already reported six months of stagnation (when accounting for inventory) previously, Q3 and Q4 last year. According to most expectations (again, FWIW), end demand did not get any better in Q1.

Those results will be posted on Thursday.

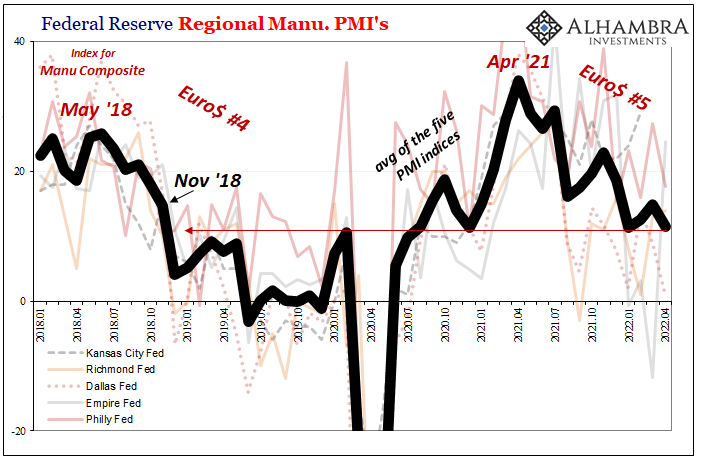

This would make three consecutive quarters of sputtering – in real terms – to go along with, much of it caused by, also clear deceleration in especially domestic US manufacturing (see: above Fed surveys that are already down below November 2018 levels). Consumers repeatedly, consistently paying more and getting less is a recipe for recession, not inflation.

There’s been a globally synchronized “feel” to what’s shaping up toward the rest of 2022. It’s not Russian, nor the next spread of coronavirus. Like the downgrade parade, slowdown/downturn/maybe more is still just getting started.

Stay In Touch