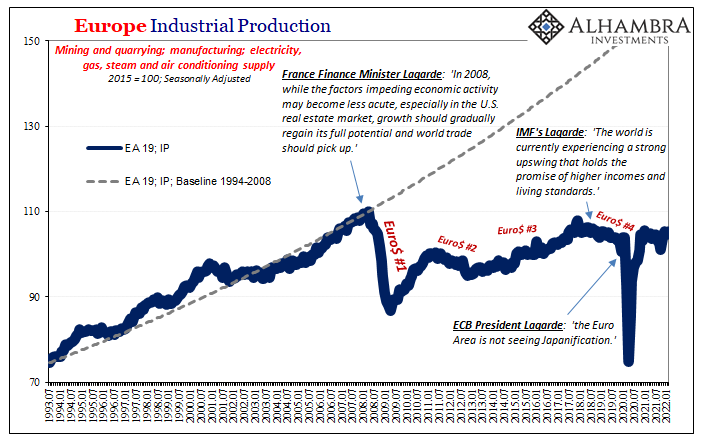

I may have to rethink my opinion of Christine Lagarde. It just may be that after helming one serious debacle after another, she – unlike most in her position – may have learned a thing or two about being too quick to call it a day. Premature celebrations were the hallmark of central banks throughout the last fifteen years, including, famously, her predecessor’s predecessor raising ECB rates…in June 2008.

Lagarde was, after all, the leader at the IMF behind its biggest disaster in history (Argentina). Famous herself for making wildly optimistic statements (below), she appeared to have every reason to stick with the type. Early November 2021 had gifted Europe’s policymakers a clear green light; or so it may have seemed.

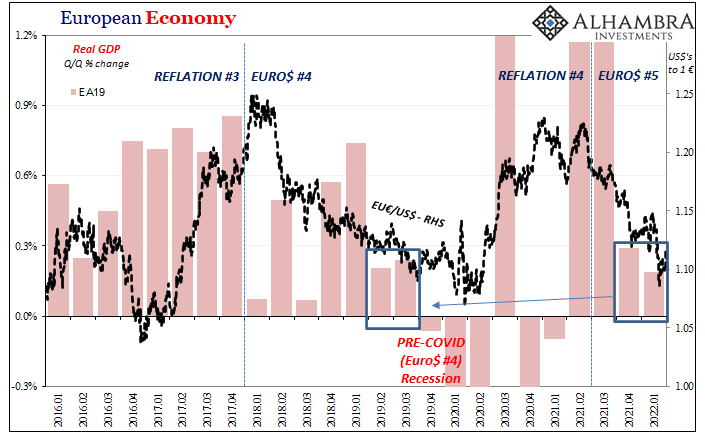

Real GDP was roaring, Eurostat’s preliminary estimate for the European economy in Q3, released in early November, up at 2.25% q/q (and that’s not an annual rate). Blistering economic stats like that along with the fact consumer prices were getting uncomfortable on that side of the Atlantic just as they were here, there must have been incredible pressure on the ECB to get going.

Over here in America, Lagarde’s counterpart Jay Powell had already cast his entire lot in with ultra-hawks.

Why didn’t the ECB follow the same path?

To this very day, officials in Europe remain committed to a far, far more cautious and deliberate approach – even as consumer prices there as in US have only accelerated further in 2022. With Germany breathing down her neck, you have to admire the unusual demonstration of backbone.

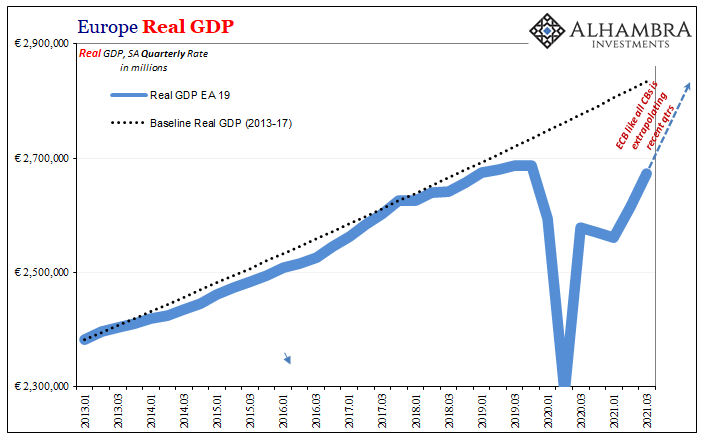

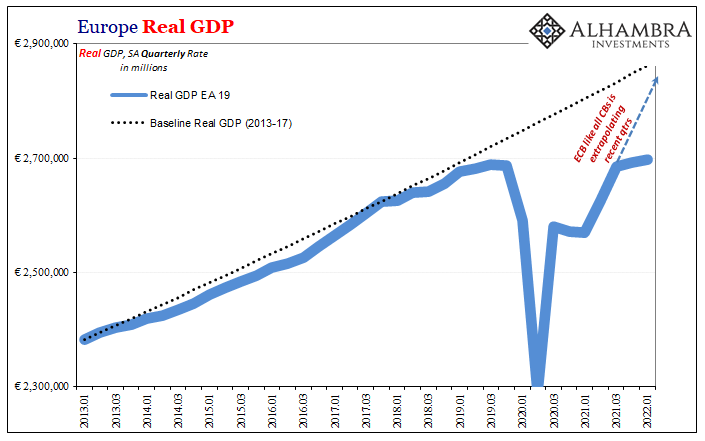

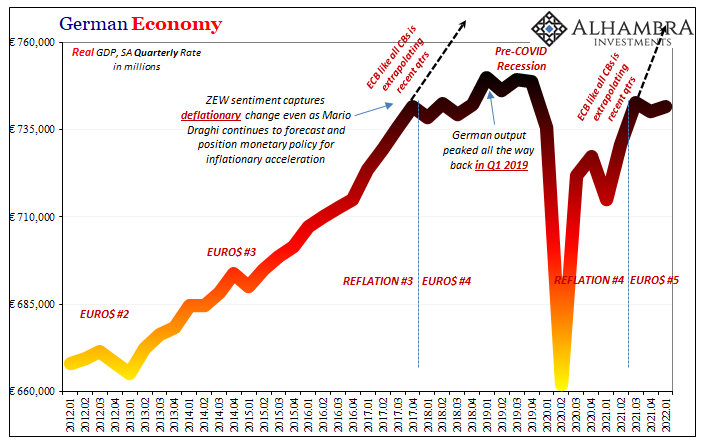

Back in November, I had, mistakenly, it appears, presumed that Christine Lagarde and those like her in Europe were incapable of seeing the errors Jay Powell and the FOMC were just about to commit again. It would’ve been so easy, too, as I had diagrammed at the time (below); as always, just extrapolate the current favorable trend forever upward and assume history will follow along in such an optimistic straight line.

First, the chart I drew back in November and then its updated version.

To her credit, she seems to have resisted that very temptation…for very good reason, as it is turning out.

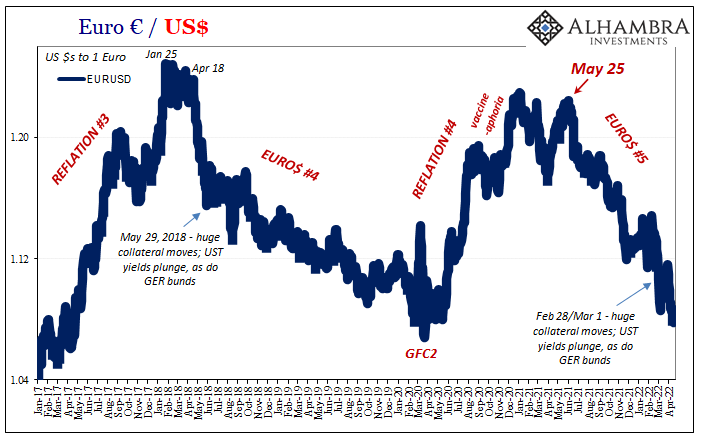

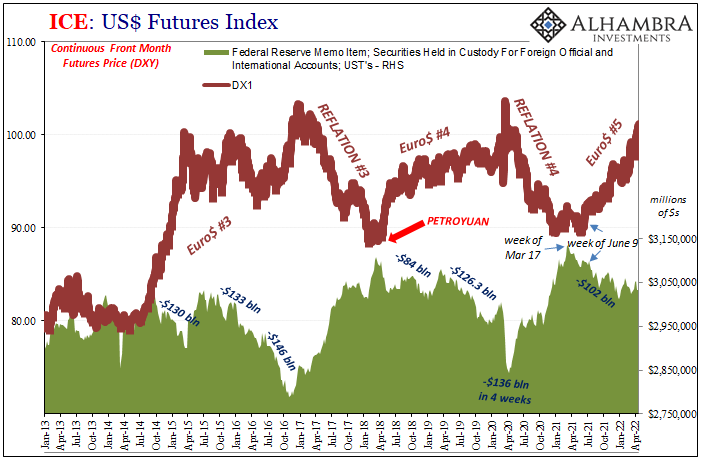

That reason, of course, Euro$ #5.

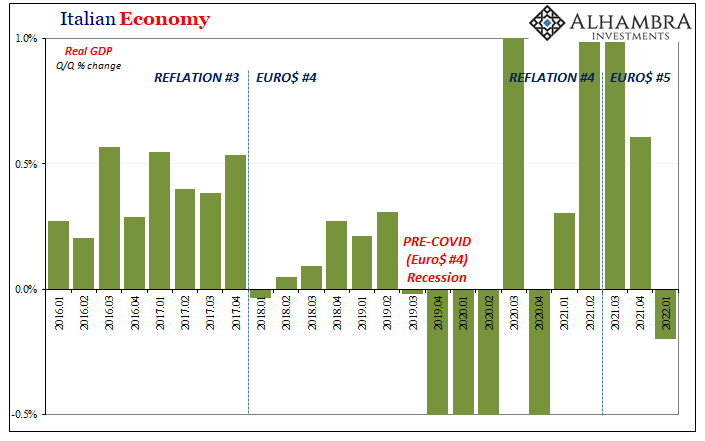

According to Eurostat today, European GDP was, for the second straight quarter, let’s just say not good. Rising 0.19% Q1 2022 over Q4 2021 (quarterly rate, seasonally adjusted), that’s actually worse than the 0.29% Q4 over Q3. Half a year in clear departure from what was really happening during Europe’s middle six months last year.

Lagarde’s legion regards this as expert policy execution when the data, like bonds, indicates something else; a delayed reopening when compared to everywhere else on the planet. This puts the European system on track to look upward at a time when globally synchronized increasingly means something different than growth.

It didn’t take long for “different than growth” to strike the Continent, either; just a single additional three-month period.

This only raises questions about why the deviation when consumer prices anywhere might make it seem as if the global economy is on fire everywhere rather than slinking downward toward a very different set of outcomes (rhymes with schm-ecession).

In terms of reopening and the like, the common answer has been COVID.

Whenever “unexpected” weakness has materialized, in whichever location around the world, it was immediately and confidently attributed to another coronavirus variant (and even that’s wrong; government reaction to the pandemic was the issue). There was some case for delta in 2021, but even that was belied by Q3 GDP’s outperformance.

Nowadays, you’ll hear about Russia and fallout from what its military is doing to Ukraine. Interestingly enough, even forecasters at the ECB (and elsewhere) weren’t expecting much from Q1 even before the geopolitical misadventure; pre-invasion forecasts proved to be off by only 0.1 pts.

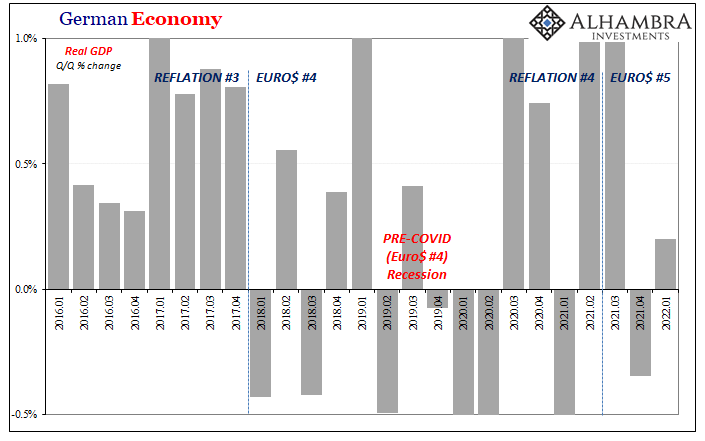

Furthermore, economic weakness is both widespread as well as synchronized. Some places have fared worse than others, yet no one escapes. Germany, for example, managed just 0.2% q/q growth in Q1 ’22 following a revised -0.35% contraction in Q4 – which simply means total estimated output remained less than it had been back in Q3.

The explanation for it can be found in the transmission of global factors, which only begin with potential demand destruction from last year’s supply shock (not inflation) driving consumer prices. As had been the case before, in particular the 2018 experience, look to financial markets and money for direction.

Euro$ #5 is all over these results, too.

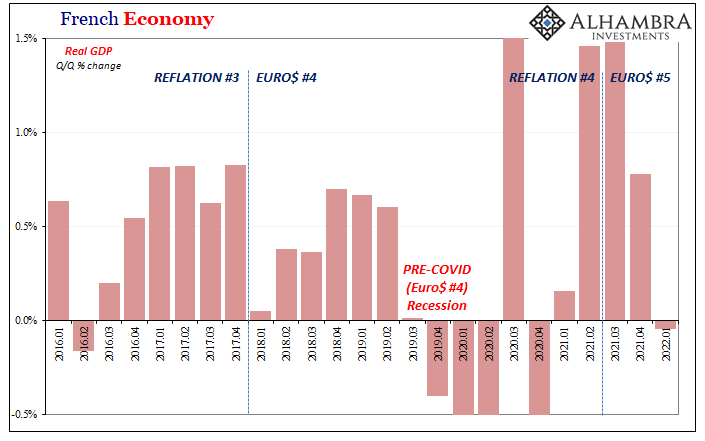

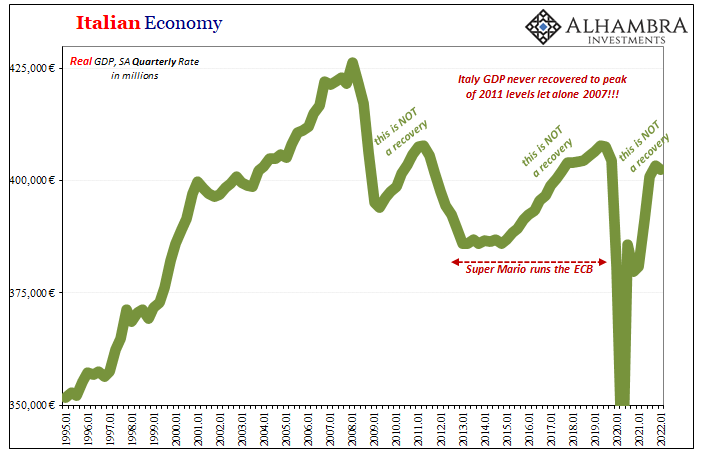

France and Italy (can never recover; see: below) round out the top three, and each of them have seen their economic momentum cut down to nothing once the initial thrust of last year’s from-delta reopening exhausted itself. One last big quarter, Q3, and then two straight of 2018-19 levels of pre-recession.

I highly doubt Ms. Lagarde has caught on with the repeating Euro$ #n commonality and cycles. But it may just be that she’s at least figured out how fleeting the reflationary periods tend to be; how they are only ever reflationary to begin with. If she’s finally made this leap appreciating at least the symptoms, it just might explain why the ECB continues to diverge from the Fed.

Then again, maybe it’s all politics or some other factor so that tomorrow Europe’s Governing Council announces a surprise speeding up to catch up with the FOMC. I wouldn’t be surprised. Call me skeptical, but I’m not yet ready to give anyone in Europe, let alone Lagarde, that much credit, not yet, even if she has already exhibited far, far more pragmatism and awareness than pretty much every other person to occupy a similar seat as she does now.

Unlike November, Eurostat has just given the ECB every reason to be doubtful and cautious of anything other than yet another false dawn.

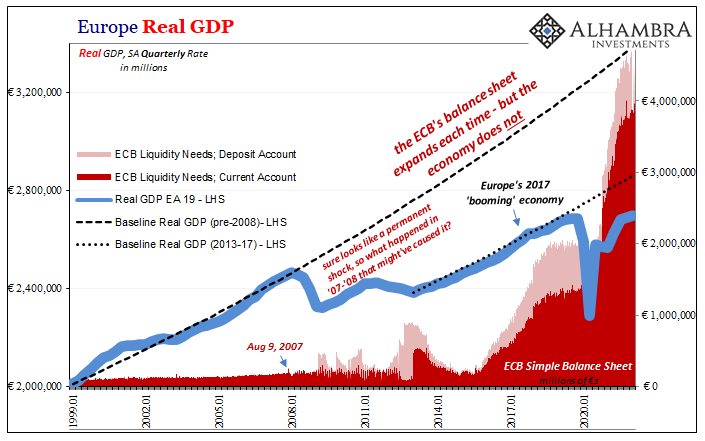

Not that rate hikes or lack of rate hikes would make a bit of difference either way. More QE won’t get the European economy going any more than past QE’s didn’t, just as hiking rates at any pace in between nonchalance and ultra-aggression won’t be able to supply more energy to the constituent countries in place of lost Russian flows.

In at least, possibly, realizing economic (and financial) results and outcomes are not closely connected to monetary policies (QE doesn’t create either inflation or recovery), that would be a good first step even if it has taken this long for anyone to have taken it.

Assuming they have. For once in the modern world, a policy obsession that isn’t totally at odds with increasingly worrisome reality.

Stay In Touch