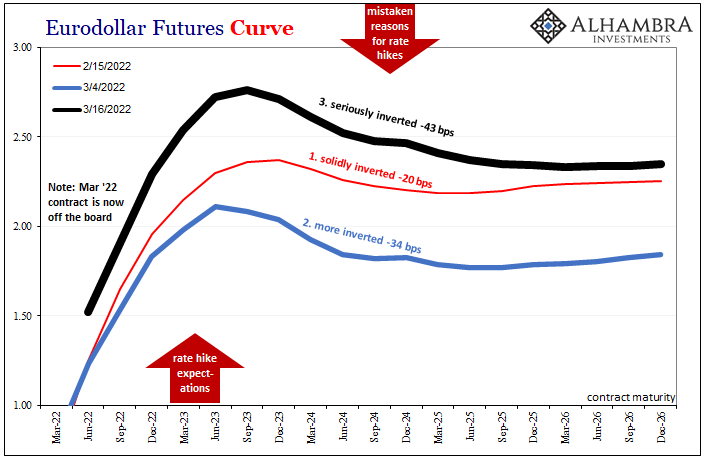

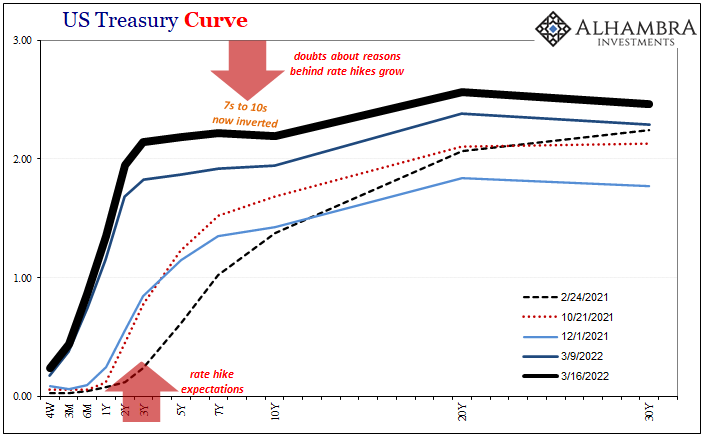

When even Bloomberg can’t help but notice, not just notice but then write about it, that’s significant. Normally a staunch water carrier for the official Federal Reserve position, these curves getting bent so far out of what would be better shapes aren’t so easy to just dismiss and ignore any longer. Jay Powell says household and business finances are holding up well, and that the labor market is good to great, a more rapid series of rate hikes (compared to 2015-18) therefore appropriate.

These curves, on the other hand, flat out disagree. So much so, the usual palace mouthpiece imagines some partial horror:

“The market is pricing in a higher recession risk and you can see that with the inversion between five- and 10-year yields,” said Andrzej Skiba, head of U.S. fixed income at RBC Global Asset Management. “The Fed is sending a strong commitment to fighting inflation.”

Is it, though?

While the article predictably goes on to attribute this high and rising recession probability to the Federal Reserve’s very own policies (the ridiculous “policy error” theory which holds a historically tiny increase in the irrelevant federal funds rate is more than enough to completely destroy something like 2018’s supposedly epic globally synchronized growth or today go so far as to turn a seventies-style Great Inflation all the way around into a recession with only threats of several hikes), it’s far, far more likely the consumer prices themselves would be the cause.

We’ve had bad and worsening global money (collateral; see: today’s 4-week T-bill compared to the raised RRP), a drag on global growth (including US; see: services) which late last year became a total “growth scare”, but now weakness and potential recession is all about the rate hikes the same media believes is capable of stopping the CPI?

Of course not. Insofar as any “inflation” fighting technique might be concerned, just how are consistent increases to IOER, the RRP rate, like the federal funds range going to extract more oil from the ground, or assemble automobiles with or without semiconductor chips?

Whether they like or not, whether they want this or not, the Federal Reserve’s non-money monetary policy has been politicized, becoming part of the partisan game of unhelpful blaming. Rate hikes are political theater, the appearance of doing something about what’s most angering the electorate.

Nowhere is this more evident than oil prices due from – not money printing – how much hasn’t been pulled up from under the Earth’s surface.

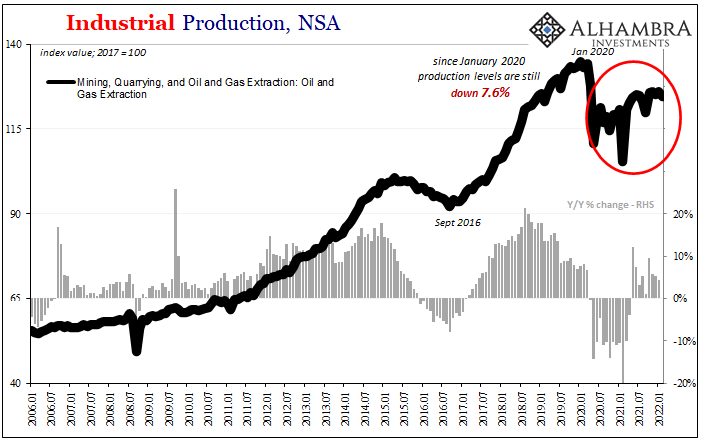

Pipeline permits, drilling leases, etc., Ukraine and Russia, the fact of the matter is here in the US oil producers continue to withhold their production – and this is using the Fed’s very own data on Industrial Production for February 2022, new figures released today.

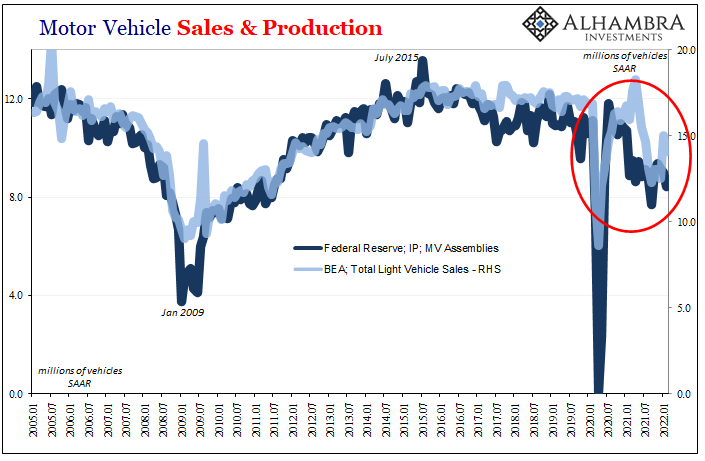

In it, not only was the production of crude oil and natural gas almost 8% less last month than it had been in January 2020, the output of domestic automobiles remains utterly depressed, too. How is Jay Powell going to change these facts? Nowhere has the US CPI been more intrusive over the last year than auto prices (spillover into used cars, in particular) and energy.

The Fed's rate hikes are going to magically manufacture more vehicles. https://t.co/f7vsRBdGGN

— Jeffrey P. Snider (@JeffSnider_AIP) March 16, 2022

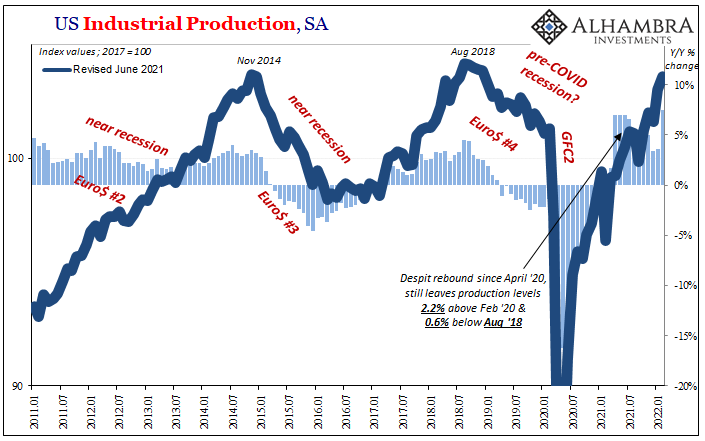

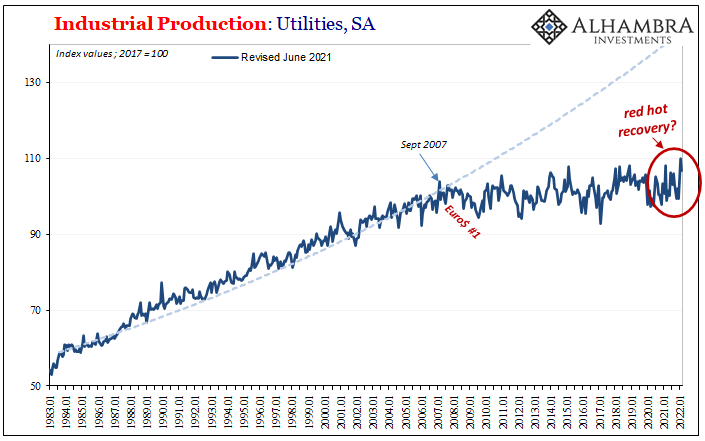

Overall IP is now up a little bit past February 2020, yet still less than August 2018 though more than three and a half years have passed and consumer prices have jumped – or consumer prices have jumped because producers aren’t producing. In fact, overall production, according to the Fed, including a massive surge in utilities the past two months, is about the same as it had been in November 2014.

There is no recovery to be found anywhere here. Rate hikes are going to fix this?

On the contrary, bond curve recession probabilities are more attuned to why production levels have struggled despite prices, having more to do with global conditions and the lack of actual volume expansion. Consumer, producer, and commodity prices have obscured, to some substantial extent, the true underlying economic situation.

It looks red hot, at least when take the narrow view of the US goods economy from its purely nominal perspective.

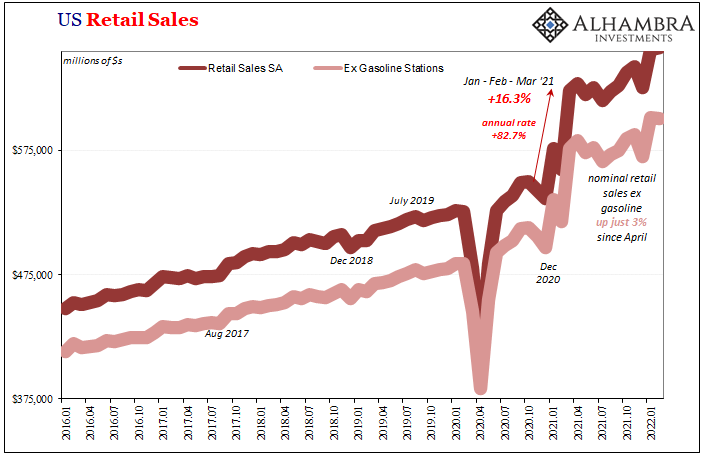

But even in that way, warnings abound. For one, the Census Bureau’s retail sales data also for February 2022 (released yesterday) shows what at first appears to be an unstoppable consumer appetite. A lot of it has been at gasoline stations, as everyone knows, but outside of filling up nominal sales have at least help up at or near their historic pace (literally off my chart, with upward revised January and February’s small monthly gain on top).

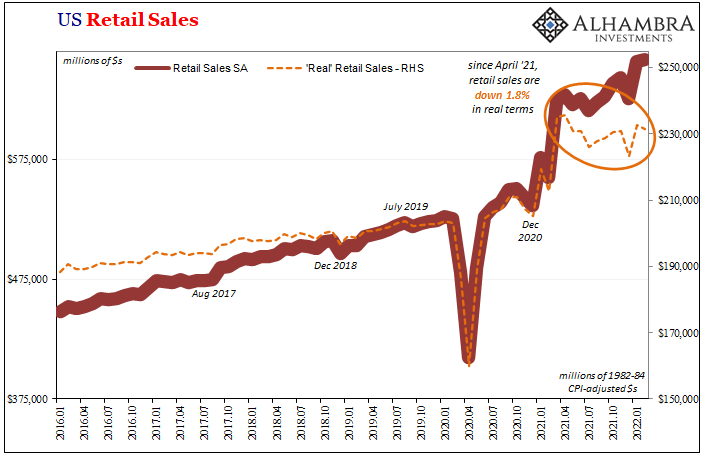

When you account for prices, though, the spending condition starts to look quite different. Real retail sales dropped somewhat in February, and are actually down almost 2% going back to last April – consumers who are, on the whole, spending more and getting less when compared to that time.

These are still high levels of sales – in America, anyway – relative to before 2020, yet they are coming down regardless even if from a historic level. The second derivative is what’s concerning here.

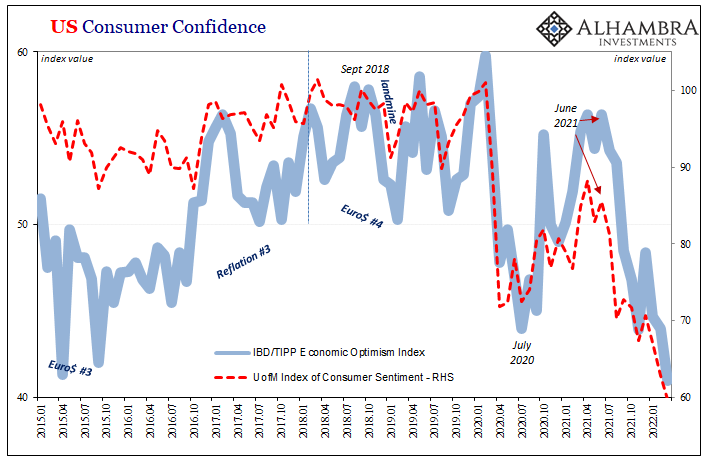

All the more so when you further consider how consumers themselves might be picturing this situation as quite different from the FOMC’s labored (pun intended) assessment. Consumer confidence is, well, deeply in the toilet (paying more, getting less along with what might be a more sluggish labor market nowhere close to full employment), while more and more data about it adds fuel to the recessionary, not inflationary, fire.

Another, Rasmussen, reported its findings a couple days ago:

Soaring fuel prices have caused a majority of Americans to drive less and reduce spending in other areas of their household budgets.

The latest Rasmussen Reports national telephone and online survey finds that 81% of American Adults say rising gasoline prices are a serious problem for their personal budget, including 56% who say higher gas prices are a Very Serious problem.

The polling firm also reported 61% who answered yes to the question, “Has the rising price of gasoline caused you to reduce spending on other purchases or activities?” Only 35% said no.

Those results put together the high level of nominal retail sales with their “real” results suggesting that for all the price changes in them consumers have at least begun to scale back if not to a huge extent thus far.

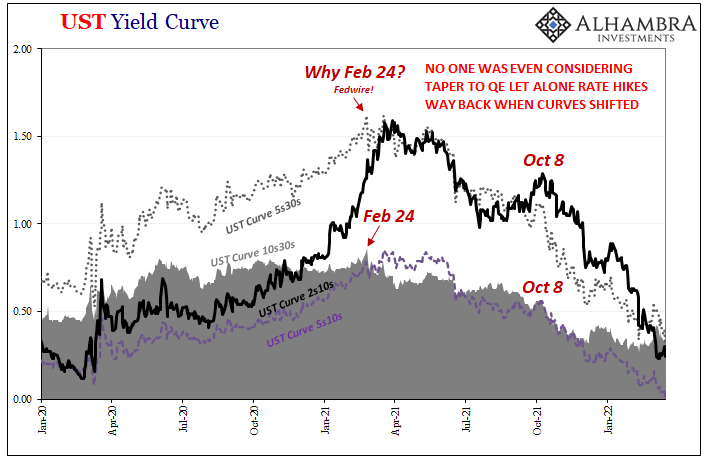

It isn’t a policy error driving the increasingly obvious and stout recession risks displayed ominously all over the place. Rather, as I wrote before, it is the policy-error error which is why these market indications go way back to when no one was even talking about tapering QE’s let alone picturing a sharp series of rate hikes out of meek Jay Powell.

All the way back from Fedwire and the effects on particularly collateral (combined with Treasury’s ill-advised cutback to bill issuance), a global “growth scare” which in macro terms was simply ignored in the media, these ugly curves and their ugly probabilities weren’t born yesterday.

To believe the Fed is behind all this or can do something useful about it, like the rate hikes you would have to be.

Stay In Touch