It’s a clever bit of misdirection. In one of the last interviews he gave before passing away, Milton Friedman talked about the true strength of central banks. It wasn’t money and monetary policy, instead he admitted that what they’re really good at is PR. Maybe that’s why you really can’t tell the difference Greenspan to Bernanke to Yellen to Powell no matter what happens.

Testifying before Congress today, in prepared remarks the Federal Reserve Chairman threw cold water on what was supposed to be the second half rebound. It still might happen, according to the FOMC’s models, but it is more and more “uncertain.”

“…it appears that uncertainties around trade tensions and concerns about the strength of the global economy continues to weigh on the U.S. economic outlook.”

The word itself is shrewdly employed in order to avoid saying the economy isn’t performing at all in the way we told you it would. Seven months ago, at the end of 2018, it was widely agreed 2019 was going to be inflation and rate hikes. Interest rates still had nowhere to go but up.

Appearing in front of lawmakers, officials have to tell them how there is now only going to be rate cuts. These are all but certain to begin in a few weeks.

Fortunately for them, Congress is a bipartisan failure on all economic matters. They’ve ceded all authority to the central bank; independence means Congressman and Senators are informed as to how good a job central bankers have done by the top central banker.

Thus, “uncertainties.” We’ve performed admirably, except for…

That’s actually the cleverest part, the one which is being widely repeated and circulated verbatim. In his statement quoted above, the Chairman is actually referring to two different things, rightly confident that no one in Washington or anywhere else will notice.

Trade tensions and concerns about the strength of the global economy. The way its being told, those are the same thing. They aren’t. What’s more, Powell knows it.

Economists, and all central bankers are them, even the ones who are not (like Powell and now Largarde), they live and die by DSGE. Econometric models are how they see the world – and themselves, the expected results of their own work. Like some ancient Greek ruler, no central banker will dare act (or think) without first trekking to consult the Oracle.

In Powell’s case, his oracle is ferbus. No matter how much they may want it to, trade wars just don’t produce what we are seeing in the global economy. Not in their statistics, certainly now in global bond yields. They aren’t big enough. There’s something else, other and more pressing “concerns about the strength of the global economy.”

But if you link these two different things together on your own, and the media helps you in that process, then so much the better for Jay Powell. Like Friedman said, and like Powell’s predecessors, the current Chairman knows a thing or two if only about PR. This is the real fedspeak.

As to the much more important view of the economy, you know it can’t be good if all the central bankers are erring on the side of caution. They see rate cuts as insurance, but insurance for what?

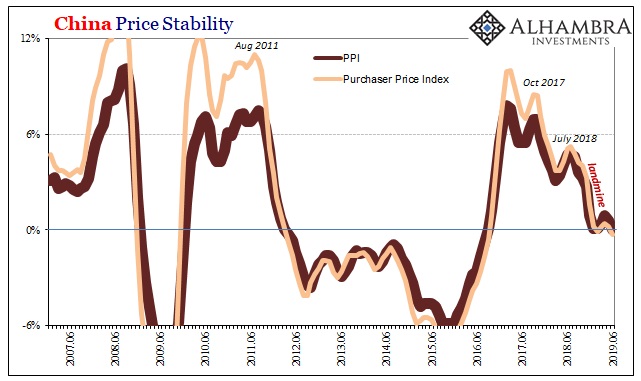

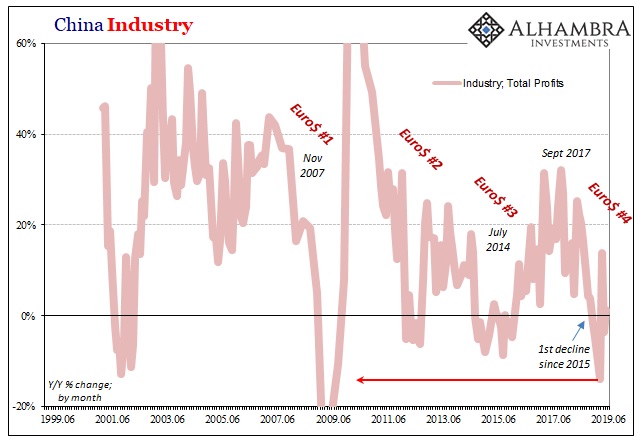

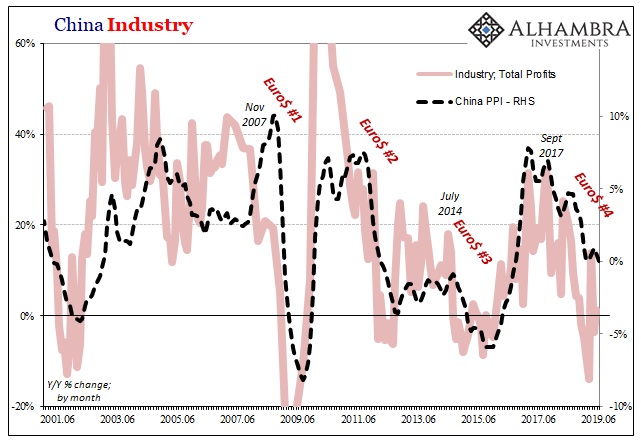

In China, producer prices were flat year-over-year in June 2019. According to estimates released today by that country’s National Bureau of Statistics, the PPI was 0.0% last month. A related but separate measure of industrial purchaser prices, factory gate prices, was down 0.3%. The specter of a return to systemic industrial “deflation” is looming over China.

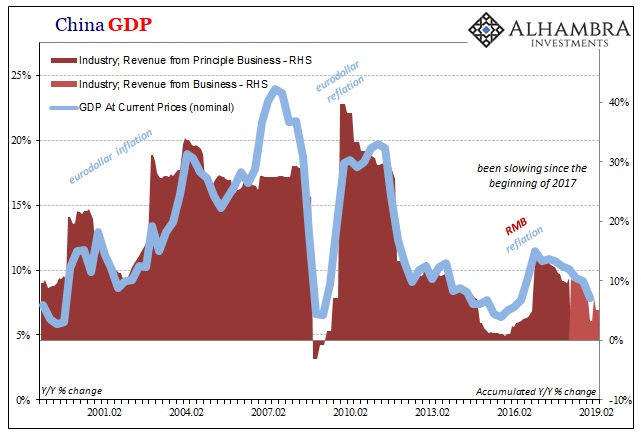

No matter how you might interpret Chinese price behavior moving forward, there’s one thing for certain: the global growth period is done. Whatever might’ve been left of globally synchronized growth, it’s now long gone. Dead and buried.

You better believe that’s what is behind “concerns about the strength of the global economy.” Without China, there is no global growth. And the Chinese PPI is at the end of the line, the final measure of output moving in the wrong direction.

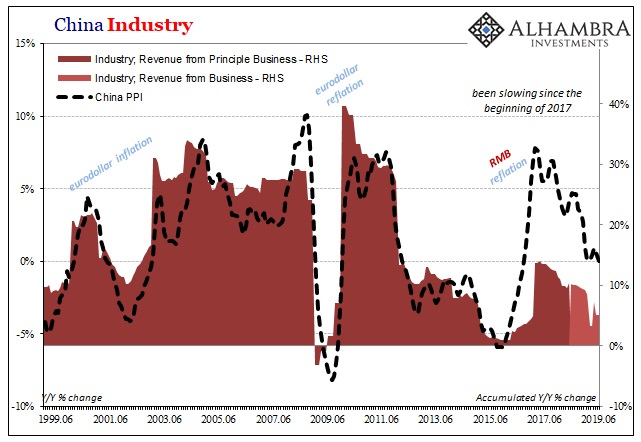

What I mean by that is simple. The PPI follows closely the conditions already observable in China’s vast industrial sector – what was supposed to be the trigger as well as the engine behind globally synchronized growth.

Revenues in industry, therefore underlying industrial activity, never did rebound despite Reflation #3. In fact, it was prices which got way, way out of hand in late 2016 and early 2017. Central bankers like Yellen took those prices to mean something they didn’t; the price spike looks much bigger than it really was simply because deflation ran unchecked from 2011 to the middle of 2016.

Simple base effects. Commodity prices weren’t up in early 2017 so much as they’d merely stopped falling and retraced a little. Meanwhile, as seen with industrial revenues, there was no recovery potential anywhere. This is why the Chinese Communists gathered in October 2017 at the 19th Party Congress to prepare the Chinese people for “quality” growth.

The Western media was too busy with inflation hysteria to notice. Japanese banks weren’t, though.

Producer prices are following the trend long ago set into Chinese industry – one that hardened long before trade wars were ever being seriously considered. No matter how many times anyone refers to “rebalancing” it just isn’t happening; China’s economy remains industrial, as does any hope for global growth.

What we see in China’s PPI and factory prices, then, is a situation that now halfway through 2019 isn’t improving. Compared to 2018, which was already a step down from 2017, the direction remains clear – particularly following the landmine.

To a policymaker like Jay Powell, this is “uncertainty.” It isn’t really. And it also isn’t trade wars. All credit to the Chairman for making it both in the mainstream view.

Stay In Touch