The Bank of Japan gathered its policymaking members in Tokyo at the end of last week. The statements released and the commentary given pursuant to it exuded a renewed darkness. When they had last met on April 26 and 27, things were already different. But the conclave before that, March 8 and 9, they were practically giddy.

What a difference a few months make, not that these Economists have any idea why.

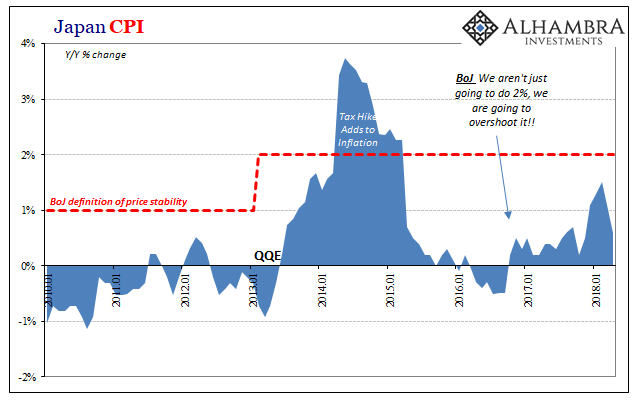

Back at the end of February, Japan’s Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications reported that the nation’s inflation rate had accelerated significantly. From just +0.5% year-over-year in November 2017, the CPI suggested a possible shift. It would rise 1.1% in December and then 1.3% in January.

The news was met with confidence at the BoJ. They began talking about exiting QQE entirely with their inflation target almost certainly in the bag. For once, things seemed to be going their way and in a clear fashion.

Though the CPI rate would accelerate further to 1.5% for February (figures released on March 23), it has since collapsed. At the April BoJ meeting the reported headline inflation rate for March was pulled back to just 1.1%. It was then that Japanese policymakers simply dropped their timeframe for achieving 2% inflation. It was there at the March meeting, as always about two years ahead, but it just disappeared from statements after the disappointment handed to them in time for their gathering at the end of April.

Between then and now, inflation has dipped further. The CPI for April, released May 18, had retreated all the way down to 0.6%, practically a complete round trip from last November. The confident smiles are all gone.

Instead, Japanese central bankers are confused. When they ever encounter this sort of unpredictable (from their perspective) misbehavior they always appeal to the absurd. In its statement last week, the BoJ lamented:

Japan’s economy is seeing labor markets tighten and the output gap improving, but prices aren’t rising much. As such, it’s most appropriate to patiently maintain our powerful monetary easing.

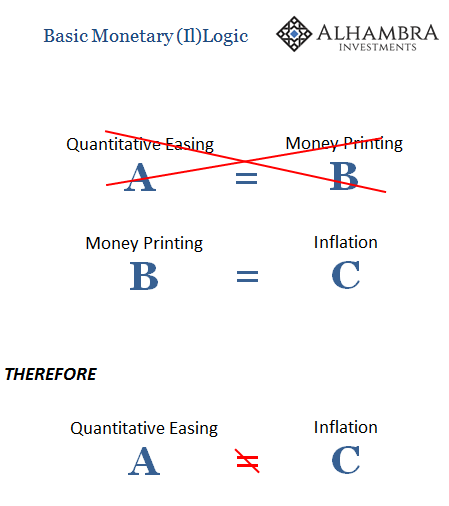

If you expect X to result in Y but it almost always comes out as Z, then maybe X isn’t what you think it is. In terms of the BoJ’s assumptions, maybe Japan’s labor markets aren’t really tight, maybe the output gap is as enormous as always, and, most of all after five years and only uncovering Z, is it really “powerful monetary easing?”

But when you claim that it is and no inflation shows up you better have something to fall back on. That’s where the entertainment comes in. BoJ officials are now trying to say that Amazon (the US-based company, not the South American jungle habitat) is responsible for some or even a lot of the inflation shortfall. Yes, online shopping has supposedly thwarted “powerful monetary easing.”

“The impact of online shopping may become the BOJ’s next talking point, but it sounds more like an excuse to me,” said Hiroshi Miyazaki, senior economist at Mitsubishi UFJ Morgan Stanley Securities.

How far off do you have to be for even mainstream Economists to find difficulty believing your story? These are people who are preternaturally predisposed to uncritically swallow and regurgitate every explanation whatever central banker might ever utter. They have been largely positive about QQE from the beginning, though the program having celebrated its fifth anniversary a few months ago really does complicate interpretations in a way it hadn’t before.

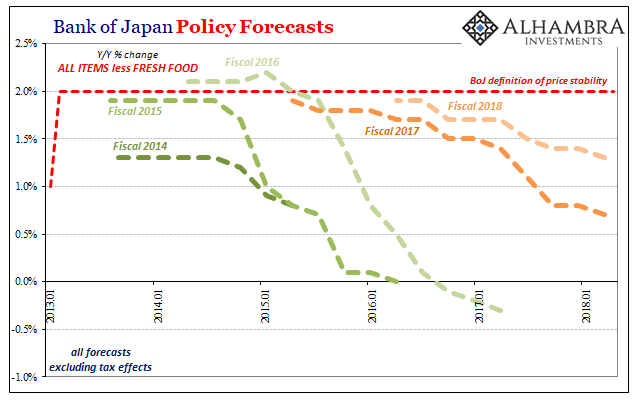

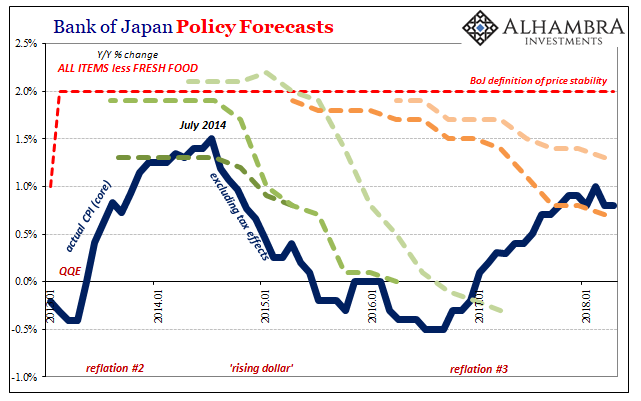

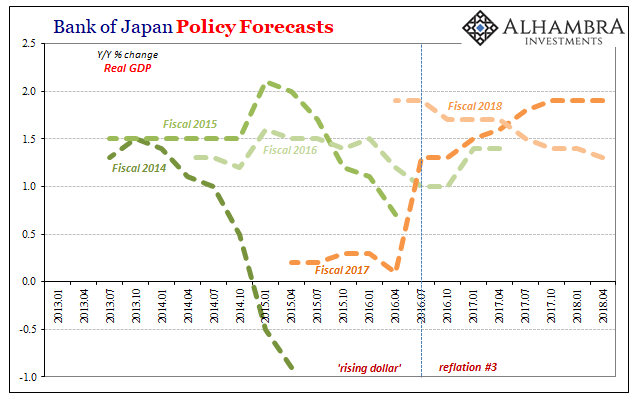

When we examine BoJ’s inflation forecasts (NOTE: all figures presented are for CPI ex fresh food, and they also exclude any impact from the 2014 tax increase), there is the obvious part to them which is constant throughout. They always start out just near the 2% target on the universal, unmovable assumption that QQE, QE, or whatever central bank policy and action will always work if only ever in the future. Over time, however, the projections are marked down as Japan’s CPI fails to rise in anticipated fashion.

However, it’s not so much where they start that draws our attention, rather it’s where they end up that really tells us something important. The bottom part of the chart reveals not just that Economists don’t get inflation, it also shows us why, as well as what it is that does matter.

Their predictions made in 2013 and 2014 were generally positive about where Japan’s CPI might end up in 2015 and 2016 but only until around July 2014. As the “dollar” “rose” and the world economy turned down, the Japanese inflation rate retreated with all that. Policymakers afterward starting adjusting their numbers as a reaction to what was already happening.

In the second half of 2016, everything reversed. The “rising dollar” ended, or at least that specific part of it, reflation taking hold in its place. The global economy started to come back and commodity prices anticipated positive implications for the shift. Japan’s inflation rate started to rise and so BoJ forecasts weren’t marked down nearly as much for 2017 and 2018 as they had been for 2015 and 2016.

The BoJ interpreted that shift as evidence QQE was finally working, the long-sought goal at last within reach only delayed as it must have been by “transitory” factors. The media, as always, accepted this version of events despite the more obvious history (which equally applies to BoJ’s GDP predictions, too).

But if you don’t really know why the most important economic variables behave the way they do, then you as a central banker open yourself up to further deviation.

This is an important point in continuation of what I noted last week with regard to the ECB’s similar predispositions. Despite the awful history of the last ten years, and in Japan, more than a quarter century, Economists operating these global central banks are still held in high esteem. Somehow. It may just be that there aren’t any alternatives to them.

A good many market and economic agents still base what they do on the idea that central bankers largely know what they are doing, even if they make mistakes. But if you as a market participant thought that in 2016 and 2017, and therefore bought into globally synchronized growth because they said it was coming, you might react harshly if (when) it is revealed they had no idea why things may have improved at that time. Betting on blind, dumb luck isn’t ideal.

Not only that, you might further worry yourself over the prospect that if they didn’t know why things picked up back then, it stands to reason they probably won’t know if and how things might change again for the worse – like in 2014. If central bankers can’t really account for the upward shift, then what might that propose about downside risks?

And if they start to blame Amazon, well, that’s just about the time to pull “dollars” out of Argentina, maybe even India. And then contemplate where to derisk after those.

Last year, 2017, was really about “what.” The global economy despite the predictably heavy rhetoric never did produce momentum. Sure, there were plus signs practically everywhere, but that’s never a sufficient condition by itself for what everyone was talking about. In place of that momentum, the mainstream explanation was one for time – it’ll show up next year.

So far in 2018, a big chunk of the world has instead moved on to “why.” In the face of further evidence for they really don’t know what they are doing, the world just doesn’t look at all as hopeful as it did in late 2016 and early 2017. The further we go this year, the more, not less, it is shown that these Economists just don’t have any idea what’s going on underneath.

Japan’s CPI is a big deal on that side of the Pacific as the Bank of Japan struggles to overcome an incomprehensible amount of failure. But as “powerful monetary easing” comes up short yet again, it’s not really about Japan at all. Escalation.

Stay In Touch