I do get a big kick out of the way Communists over in China announce how they are dealing with their enormous problems especially as they may be getting worse. Each month, for example, the country’s National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) will publish figures on retail sales or industrial production at record lows but in the opening paragraphs the text will be full of praise for how the economy is being handled. If you thought the Western media was liberal with the word “strong” (经济强劲, I believe) you haven’t read an NBS press release.

This week it is the PBOC’s turn at spin. China’s central bank released its annual financial stability report on Monday. You won’t be surprised to learn that the Communist government has pretty much cleaned up everything that might bother rational thinking people, but also remains vigilante because there continues to be so much more for rational people to be bothered about.

Overall speaking, China’s financial risks have been slowly resolved but the risks are still abundant, after accumulating rapidly in the past few years.

Unless something is being lost in translation, you see what I mean.

On the hunt for “black swans” and “gray rhinos” (the metaphorical kind, as in the rare animal evoking tail risks, rather than RHINO’s which the media in 2017 once talked incessantly about looking ahead for both Janet Yellen and Zhou Xiaochuan), the central bank is all over anything that’s wrong. Because there is so much that is.

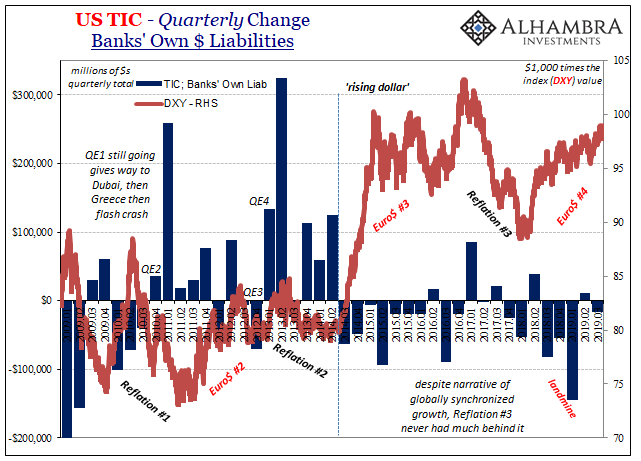

The PBOC is worried about what it classifies as possible “abnormal” market fluctuations due to “externalities” – particularly as they might relate to “global liquidity.” Sounds vaguely familiar.

Authorities did caution, however, that at least in the short run China’s economy could get a whole lot worse. While those in the West are itching to play that up as the costs of ill-advised “trade wars”, that bit about “global liquidity” pushes the discussion in an entirely different (for the media “unexpected”) direction.

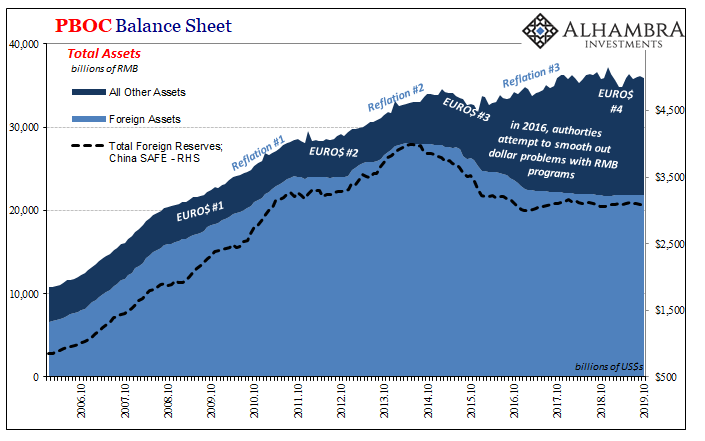

If you actually look, which most people never do, it’s not hard to see what and why. You need only a rudimentary knowledge of central bank accounting and an internet connection to log into the PBOC’s balance sheet figures. Everything you need to know is right in front of you.

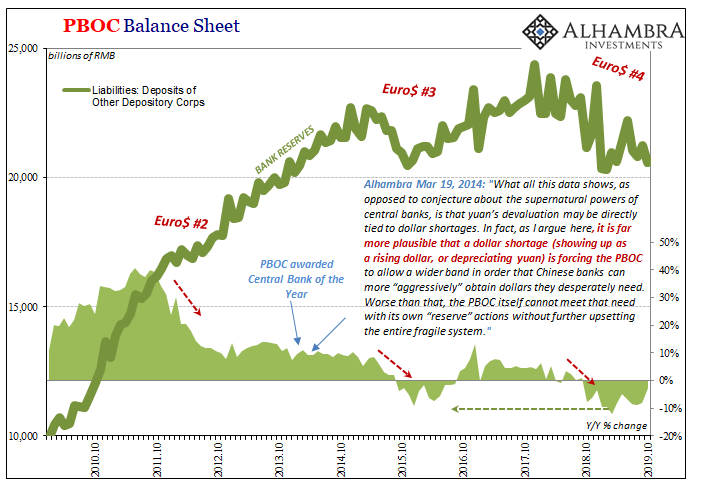

What the central bank reported for its October 2019 statement of condition was largely more of the same. The most glaring monetary hole in its balance sheet statements for going on two years continues to be bank reserves (Liabilities: Deposits of Other Depository Corporations).

Speaking of externalities, that’s all this is. The eurodollar market stops providing China with “dollars”, or makes it that much harder for its banks to source them (from Japan, mostly), fewer end up in the monetary authority’s hands. Without that push on the central bank’s asset side, the liability side where all the money is gets caught in a vise. The eurodollar squeeze becomes an RMB strangle.

Since the PBOC can’t tell the government to hold less cash, it can only cut back the growth rate of currency issued while at the same time reducing outright the number of bank reserves.

At first glance, October’s balance for that line doesn’t seem all that bad, especially not in comparison to the collapse over recent months. Year-over-year, bank reserves were down just 2.8% last month when they had fallen by more than 8% in each of the three months prior.

But that only goes to show just how intractable the shortage has been, the length of time involved in the PBOC being stuck between the rock (financial stability) and the real hard place (eurodollars). The reason for October’s less negative rate was simply base effects – bank reserves in October 2018 were already down by 7.9% from October 2017. Last October was the first big decline of Euro$ #4 (the landmine warning).

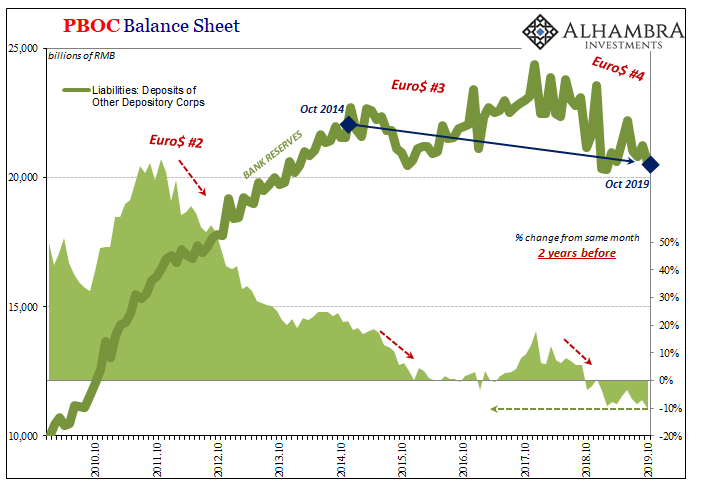

Never a good result, the monetary contraction is now lapping itself on the calendar. Putting it all into a longer-term perspective, you begin to see just how serious things have become when compared to what now seems like ancient Chinese history:

Just comparing bank reserves in October 2019 to those in October 2017, they are down by more than 10% which, as you can plainly observe above, is the worst 2-year change in history. To put it in context (not shown above), between July 2006 and July 2008 (when Phase 2 of Euro$ #1 finally hit the entire global dollar system), bank reserves in China more than doubled, increasing by 126.3%.

Nowadays, as the blue arrow above illustrates, China goes half a decade without any sustained monetary growth here (October 2019’s balance is 4.5% less than October 2014’s). And this is now normal even if it has never once been reported anywhere. Instead, RRR’s are uniformly classified as “stimulus.”

It’s as if, right around late 2014, China hit a very real monetary wall. Again, the word is externality.

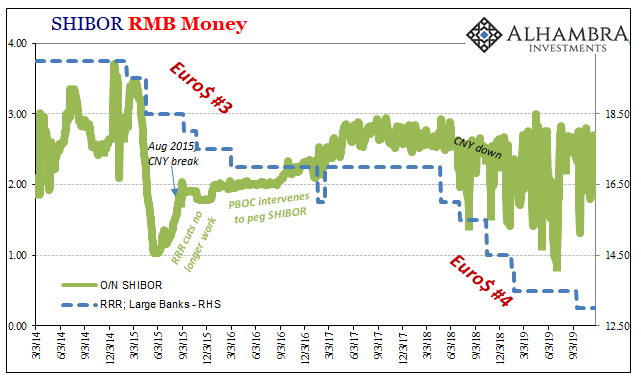

As we’ve noted ever since, authorities have attempted to offset this deficiency in a variety of ways; there have been interest rate cuts, recently renewed in November 2019 in a small way; Hong Kong; most of all that increasingly desperate appeal to China’s banking system to put more of its own reserves into the pot. RRR cuts.

The banking system especially during these eurodollar squeezes tends to ignore or refuse the invitation. You can plainly see that, too:

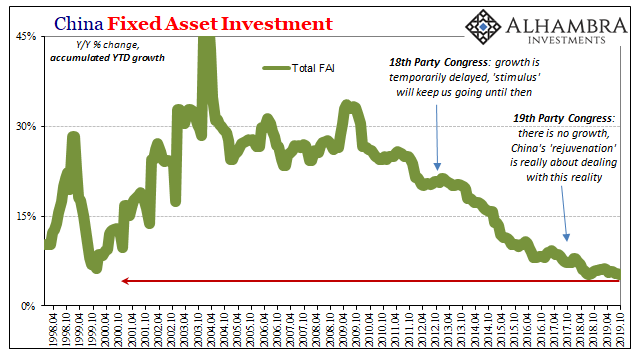

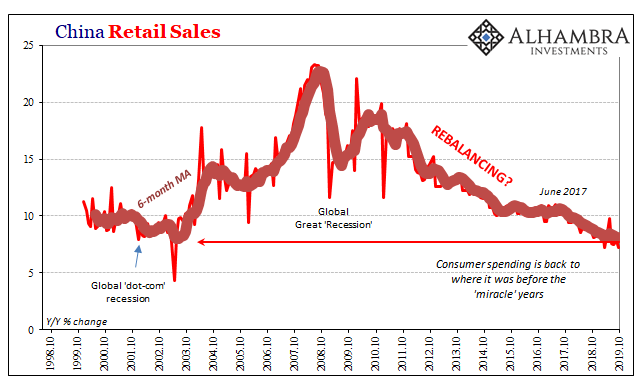

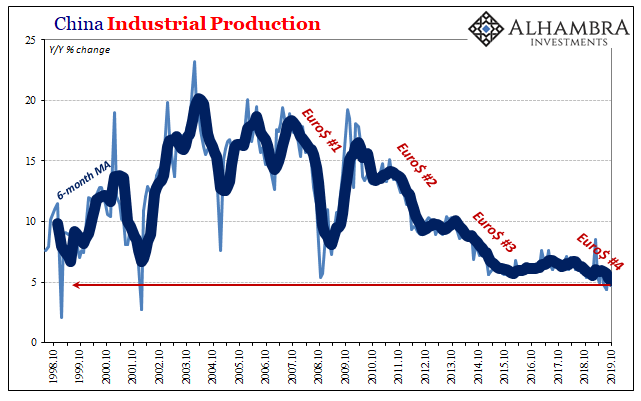

That leaves us with what really should be a simple evaluation: how has it all worked out for China? Since our evaluation period extends way, way back before “trade wars”, you also get a good sense of how what the PBOC is talking about as far as externalities isn’t those.

In short, how has the Chinese economy performed in the face of growing eurodollar headwinds beginning around 2012, those that began picking up and turned into a maelstrom around 2014?

The question very obviously answers itself. When China was most expected to contribute toward a global recovery, 2014 and 2017, its economy remained instead under the most heavy and consistent external monetary pressure. By unintentional initial design, the Chinese monetary system has left the country with the world’s biggest dollar problem during this decade of chronic dollar problems. China absolutely wants to change the global reserve system, but lacks every means to do so.

The good news, I suppose, is if you believe (hope) somehow that the eurodollar problem is going to end in the near future. The bad news is, after so many years of this, there really is no legitimate basis to believe such a thing. That’s about the best way I can sum up the PBOC’s financial stability annual.

Stay In Touch