Supply glut or demand disappearing? We are back to asking that question again after four years. In late 2014 and early 2015, the conventional answer was shale. The US had begun producing so much oil there was a glut of supply. Without an outlet for it, all the crude began building up primarily in Cushing, OK.

All that was true but also never came close to explaining the oil crash. What changed wasn’t supply it was demand. The oil futures market had known about the onrush of additional crude production for a long time before the summer of 2014. There were no surprises on that side of the ledger.

Instead, it was perceptions about how much of that supply would get used and how quickly. That year had started under vastly different expectations than it ended. Though everyone talked about the “best jobs market in decades” and how the Fed was going to aggressively raise interest rates (this sounds familiar), the oil market could already tell the demand side wasn’t living up to robust economy expectations.

Fast forward to the middle of last year. Production is and has been rising, a perfectly predictable path for supply. Beginning October, suddenly crude prices plummet again – not quite as bad as 2014-15, but WTI started from a much lower level this time around (saying something about Reflation #3).

What changed?

In literal terms, what changed was again inventory which only brings us back to the supply versus demand question.

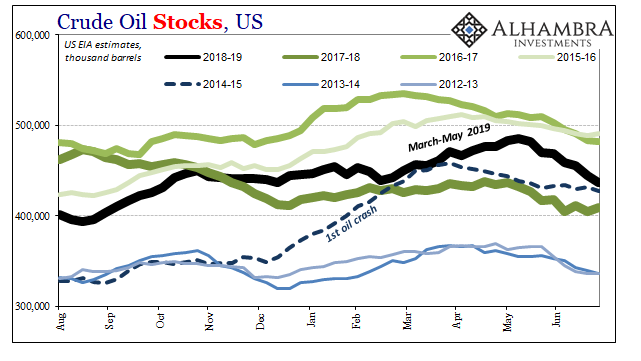

Domestic crude oil stocks had been drained throughout 2017 and early 2018. The trajectory wasn’t quite normalization, which would’ve meant levels more like before the 2014 oil crash. But still, compared to the worst in 2016, inventories were definitely improving. Though globally synchronized growth wasn’t living up to the hype, it was still the right direction.

You can see the change in inventory more easily below:

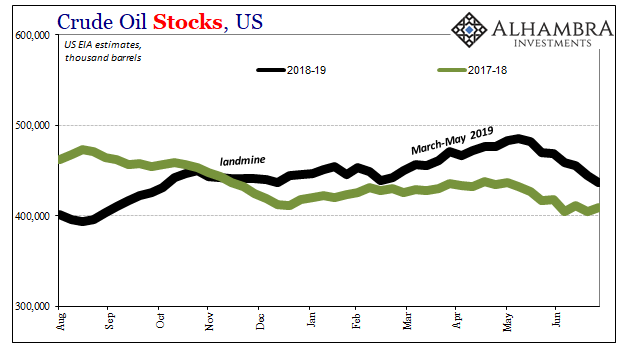

Right around September and October 2018, domestic inventory levels bottomed out and started to rise again. Even factoring regular seasonal accumulation, there was more oil than there “should” have been given all the talk of rate hikes and inflation. WTI futures picked up immediately on the change, the end result being a financial landmine – the shocking contango curve instead of backwardation.

It wasn’t just oil futures where this landmine detonated. It was a comprehensive, worldwide affair. Global bond yields, even the stock market. Consistency from top to bottom – from the monetary world to the financial world to the real world of physical oil.

Something had changed and it wasn’t crude supply.

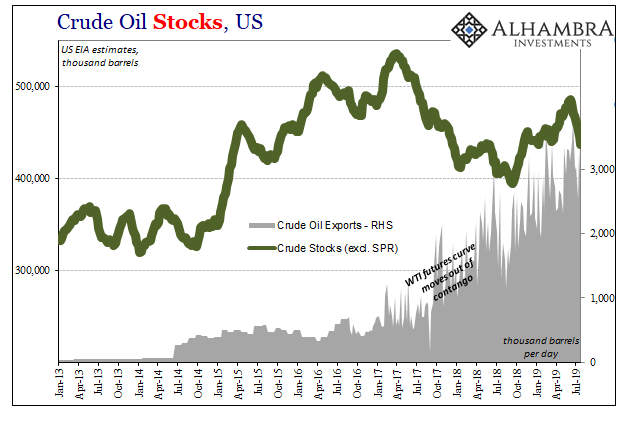

To emphasize that point, the US continues to export more of what gets pumped out the ground inside of its borders. Even as domestic crude stocks started upward again, domestic producers have been able to dump more and more of the black stuff onto overseas markets.

In other words, the demand problem is likely worse than it otherwise appears in rising crude stocks. How much inventory would be stuck in Oklahoma if the export ban hadn’t been lifted a few years ago? It probably would’ve looked a lot like 2014-15.

It’s another factor which demonstrates how something substantial had changed in the middle of last year.

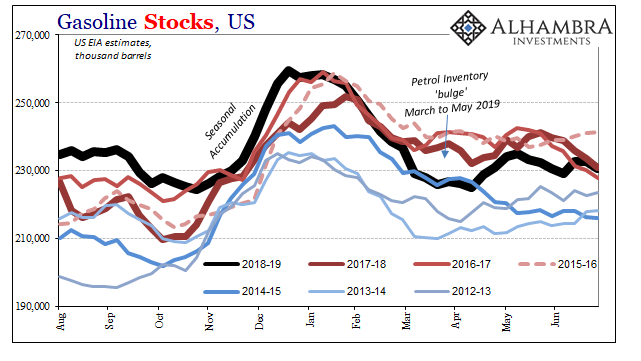

Whatever it was, it continues to be a problem this year. From March to May, crude inventories rose again as gasoline stocks were drawn lower. Instead of holding distillate inventory, and paying the costs of converting, the supply chain has reversed from its end point.

Despite this far more cautious approach, gasoline stocks have rebuilt themselves anyway particularly over the last few months.

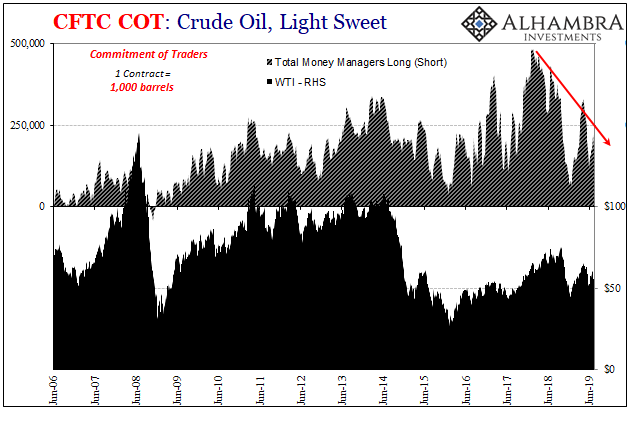

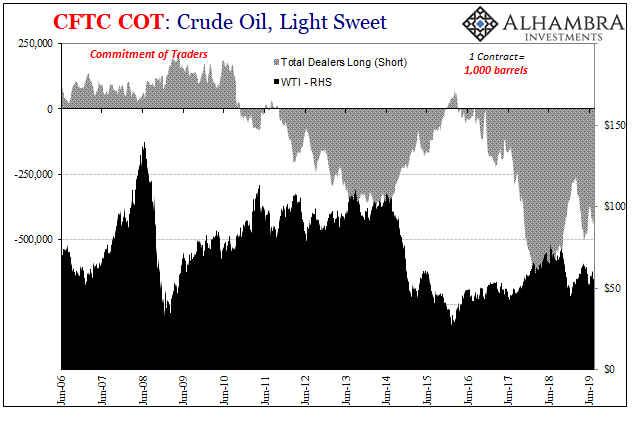

These outlines rather obvious bulges haven’t been lost on the futures market. When prices rebounded from the January 2019 lows, there were fewer betting on the Fed “pause” to square demand with supply than had been betting on inflationary recovery at the prior price peak.

When the March-May inventory build showed up, fewer still have been betting that a more dovish Fed including rate cuts and an early end to QT will balance the market via “stimulus.” A second half rebound? Not in these prices.

What we see in the oil market is representative of the general process of rethinking expectations beyond Cushing, shale, and commodities. Going from globally synchronized growth unbothered by whatever happened on May 29, 2018, to September and October wondering why crude was starting to pile up and then investors hitting the sell button in unison as it did.

They came back early on in 2019 a little chastened hoping that maybe there might still be some monetary policy magic in Jay Powell (but not really buying it with conviction). Perhaps the demand problem and the Q4 landmine really was “transitory”, not a determined break in the trend.

Instead, gasoline pushed back into crude and then even more inventory where green shoots were supposed to materialize. There’s a sinking feeling that the demand imbalance isn’t temporary at all, coming up as a sinking crude oil price heading back toward the $40s again.

I’ll end by reprinting something I wrote in February 2015 because these things just repeat. What is it that has changed over the last year? Same thing as before, the other side of the equation which is much harder to predict (especially in a world with so many false dawns).

In order to believe that crude prices are solely a supply problem you simultaneously have to believe that futures investors are all stupid. This is not to say that they are never wrong, but in this case it would mean that they cannot even perform basic tasks of financial discounting in order to set an orderly and clearing market price. That is the only way you can look at “record supply”, which is clearly the case, and think it has anything much to do with the collapse in oil prices.

Stay In Touch