Whether we notice them or not, there are a lot of things that do happen on a seasonal basis. Economists have tried to eliminate these patterns from our thoughts and analysis largely by smoothing them out with seasonal adjustments. But in money as markets there remain these bottlenecks.

People have asked me from time to time why I use the June contracts to plot out eurodollar futures (EDM) and their curve. There is no specific convention, and the June’s hold no special properties that make them stand out over and above the other three round lots (March EDH, September EDU, December EDZ). They are, essentially, my own shorthand, a term of art developed from the realization of underlying repetition.

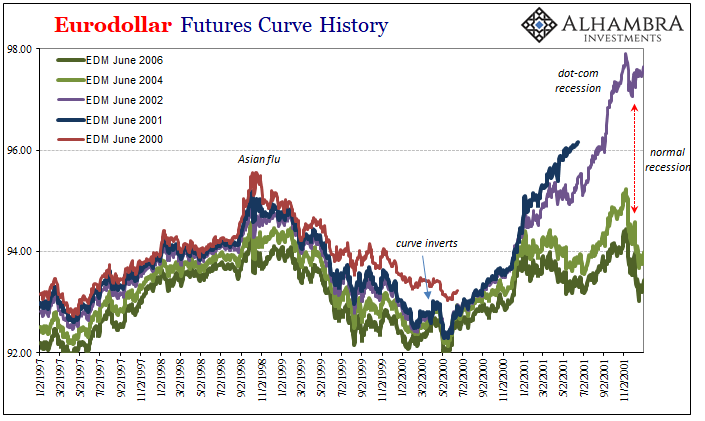

Everything always happens in summer, which makes the EDM’s particularly handy for marking noteworthy time inside one’s crowded mind. As noted yesterday, eurodollar futures turned against Alan Greenspan after one rate hike on August 10, 1999. The entire system broke August 9, 2007. The FOMC actually debated a repo market bailout on August 9, 2011. The big Chinese “devaluation?” August 10, 2015.

Coincidence? Yes, partly. In complex systems, though, we should expect these kinds of strange attractors.

In the stock market world, the cliché is sell in May and go away. There’s something to the saying, though far more importantly money than stocks. Reset your internal analysis clock at the expiry of each EDM and it helps recalibrate certain expectations (very different from those in the mainstream).

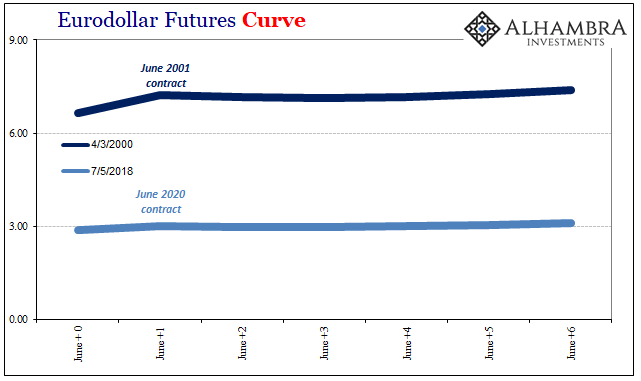

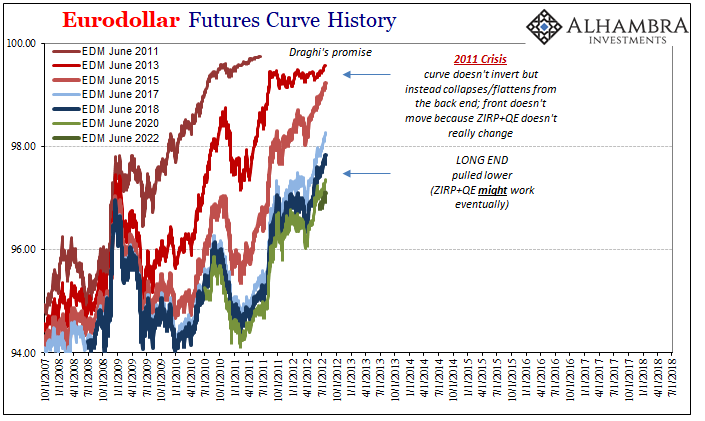

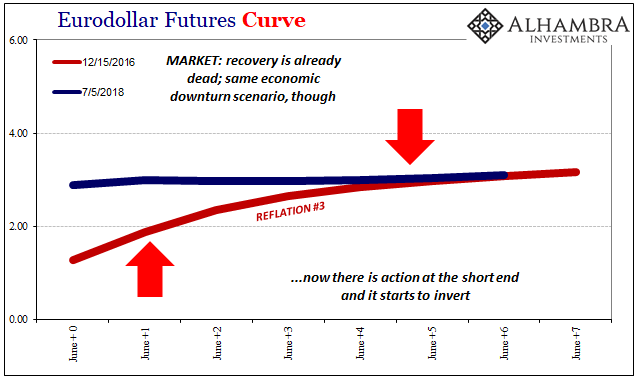

There is a ton of information contained in these curves, using June contracts to display them or some other convention. Yet, only now do they get noticed. The eurodollar curve is the first to invert in 2018, but in some ways that proposes something is different. That’s the wrong idea. Dead wrong.

People only care about them in the context of the traditional business cycle. There was a major downturn in 2012, but no inversion. Does that mean the curve didn’t apply, or that it only matters specifically for recession forecasting?

By focusing exclusively on the recession part, convention has missed everything that has truly mattered. The eurodollar curve, like the Treasury curve, has been remarkably consistent even if nobody noticed.

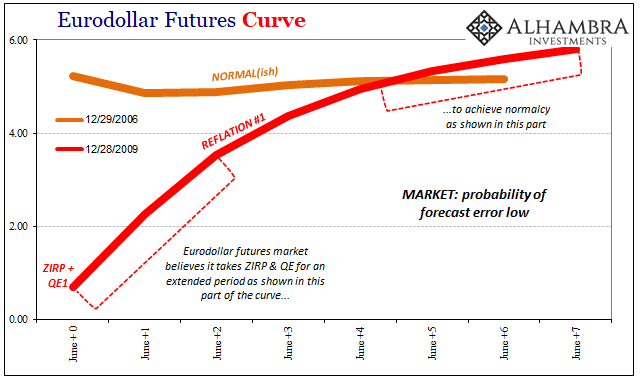

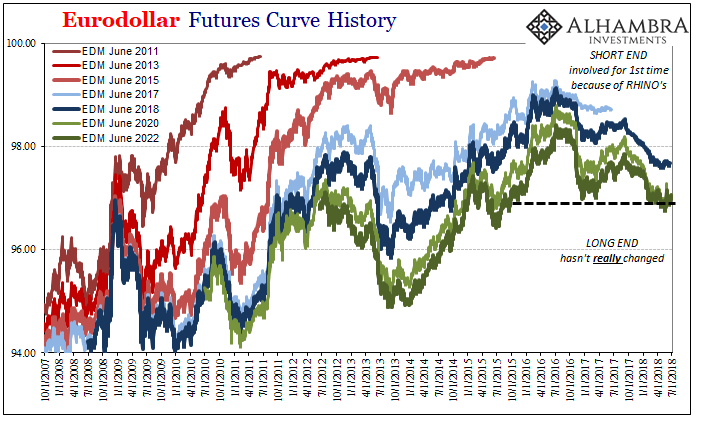

Take the initial curve following closely the aftermath of the Great “Recession” and global “dollar” panic. It looked very much like the one at the end of the dot-com recession, steep and wide which in broad terms meant a market expectation each time for full recovery.

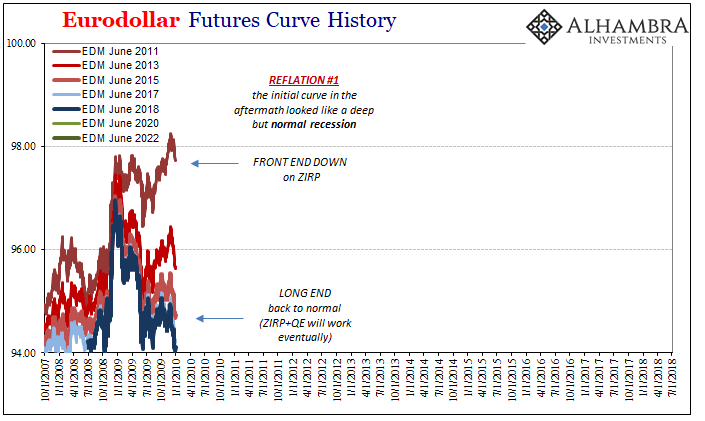

But that was interrupted by events in 2010 and particularly 2011. The curve was there, too, especially with so much that had happened clustered around the months of May through August. The downturn that followed was severe enough: a near recession here, a full recession in Europe, and a marked (and so far permanent) slowdown across China, Asia, and the rest of the world.

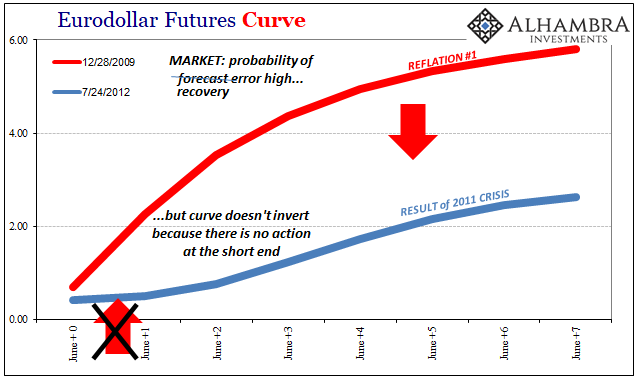

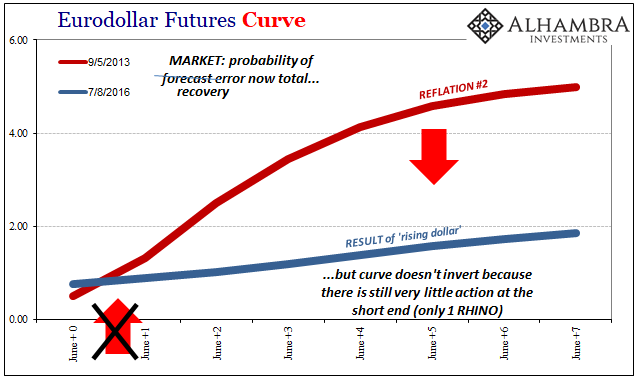

The only reason it didn’t invert was because there was nothing going on at the front or short end. That’s it. All the action was in the back at the long end. The absence of the Federal Reserve in all this explains why nobody cared or noted the unambiguous signal; most of all central bank officials. That didn’t mean the curve action was unimportant, rather it suggests why monetary policy can’t ever get out of its own way.

The collapse rather than inversion through 2011 and on into 2012 was a desperate sign, far more calamitous than mere recession probabilities (permanence, long run stuff). It meant that not only was the probability of forecast error way too high, furthermore the very recovery itself was at risk.

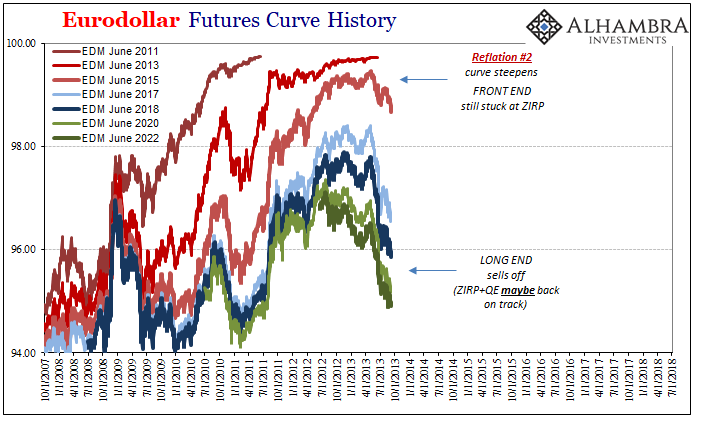

These extreme positions temporarily abated following first Mario Draghi’s July 2012 euro “promise” and then the implementation of QE3 and QE4 in the United States. Again, all the action was at the back; the curve steepened on somewhat reduced pessimism about future prospects. It never reached back to normal because there was enough going on in July and August 2013 to keep everyone (who noticed) on edge.

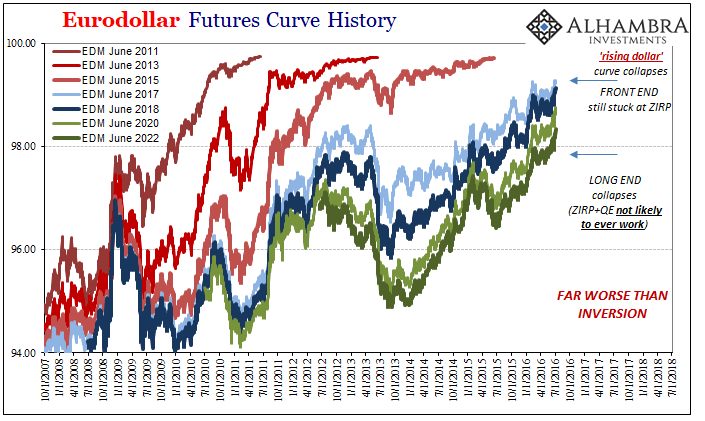

Of course, what followed in 2014 and beyond was even more extreme – and still largely unreported, certainly misunderstood. Again, the “rising dollar” and its devastating effects didn’t bring about a curve inversion because like 2011 there wasn’t much going on at the front. By the time it was over in July 2016, the Fed had conducted but one single irrelevant “rate hike” compared to the utter devastation (about future long run prospects) in the rear.

The recovery was declared, essentially, dead. Total. Complete. But because the Fed wasn’t really involved, for most of the world it didn’t happen. No curve inversion, no attention. That’s the big problem.

The collapse of these curves is paramount for every piece of additional analysis, from China to Brazil to US motor vehicle assemblies derived from flat to nonexistent income growth. Anecdotes about the non-existent labor shortage multiply and amplify because in the media they never noticed by just how much the unemployment rate had been so thoroughly debunked by these curves. If there was boom, it would have been found here with interestingly positive months beyond those connected to always June’s.

Inversion is the last thing that would matter. All it signals is the same downturn risks only without any hope of upside recovery. There is but only the one difference, and for all that matters that difference just doesn’t matter. Everyone thinks it does, though, which is why the last ten, eleven years have proceeded without anyone doing something about it.

Stay In Touch