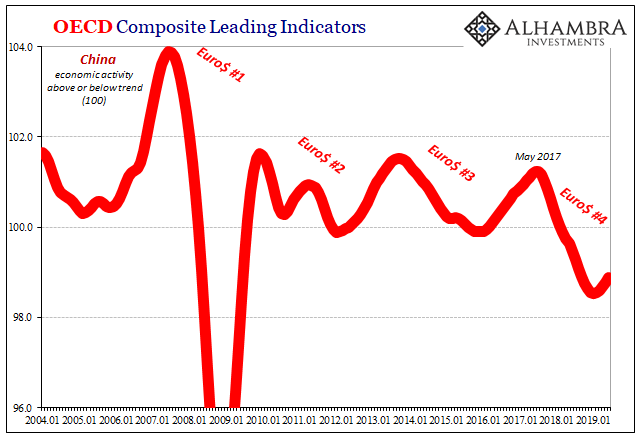

The last time was bad, no getting around it. From the end of 2014 until the first months of 2016, the Chinese economy was in a perilous state. Dramatic weakness had emerged which had seemed impossible to reconcile with conventions about the country. Committed to growth over everything, and I mean everything, China was the one country the world thought it could count on for being immune to the widespread economic sickness.

That’s why in early 2016 authorities panicked into another huge, and wasteful, spending spree. In much of the West, it was seen as the government coming to its senses. For reasons that remained unclear (particularly that whole bit about CNY falling), the country experienced a momentary lapse of reason but regained its senses in time to re-open the Economics textbook to the chapter on Keynes.

Because of that, 2017 could open back on the right track for the first time. Globally synchronized growth was as much dreaming about a resurgent China as it was anything else.

And it was also a big misunderstanding. What must Communist authorities have thought considering how 2017 was being glowingly described everywhere else? We don’t have to wonder because toward the end of that year they told us. Globally synchronized growth was a lie, an often purposeful mischaracterization of a small positive trend.

An economic mountain made out of China’s tiny, but massively expensive, molehill.

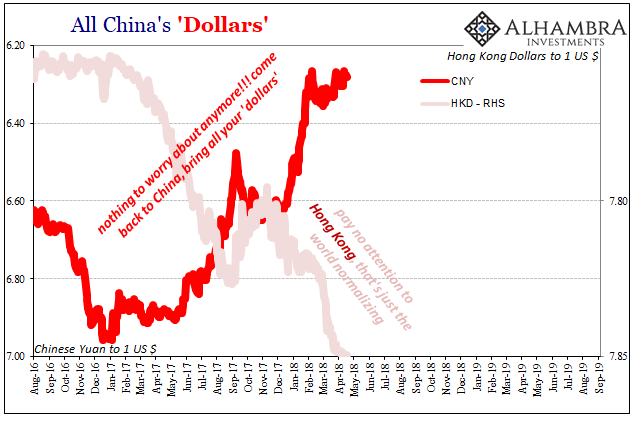

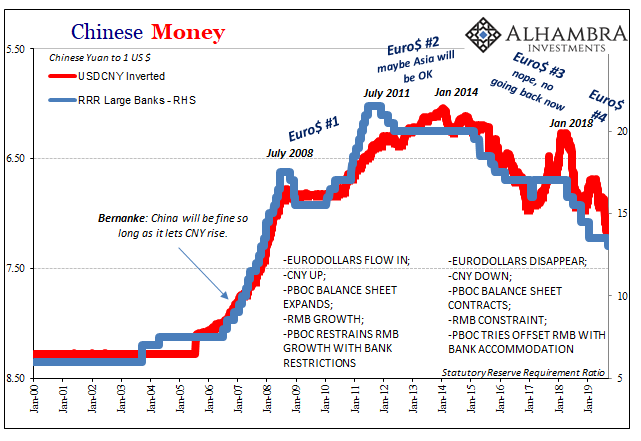

The Chinese government had tried everything in order to at least stabilize the situation after 2015-16 (Euro$ #3). Not only were the fiscal taps opened, so, too, monetary authorities brought out their creativity. The RMB stuff was typical, rather it had been the focus on CNY which was their real aim.

For all the mainstream focus and attention on internal “stimulus”, what China needed above all was dollars. Somehow, some way authorities had to convince the eurodollar system to bring a ton of them back into the Chinese structure. This was the only way to get the currency into a stable position again, and more importantly it would also represent an organic monetary contribution sorely lacking in the domestic economy.

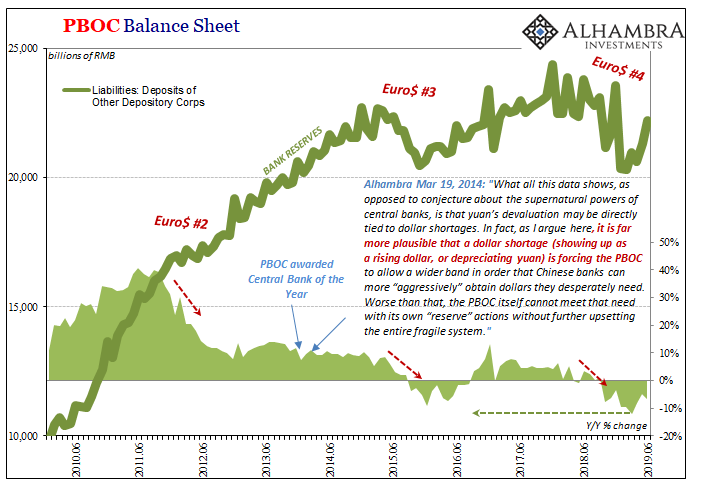

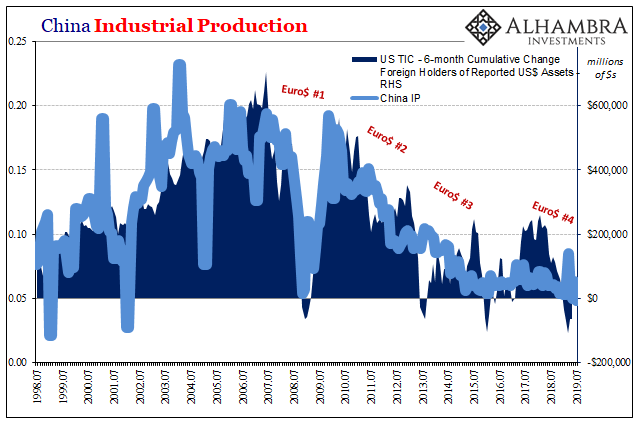

To restart or even stabilize what makes China’s economy run requires the eurodollar system to supply the monetary capacity for it. What had rocked the Chinese system starting very early in 2014 was this growing dollar shortage. It had been an external monetary constraint imposed upon the domestic monetary situation – a real squeeze inside and out.

Maybe even early on in the process, toward the middle of 2017, China’s government realized it just wasn’t working out. Globally synchronized growth or not, the dollars weren’t coming back at least not directly from the eurodollar system left to its own decisions and perceptions.

There was something very unnatural about the whole thing that year, as I wrote in review of it right at the start of the following one (January 2018). Inflation hysteria was raging throughout much of the world, and a lot of it predicated upon not seeing China in a desperate struggle where it should have been thriving.

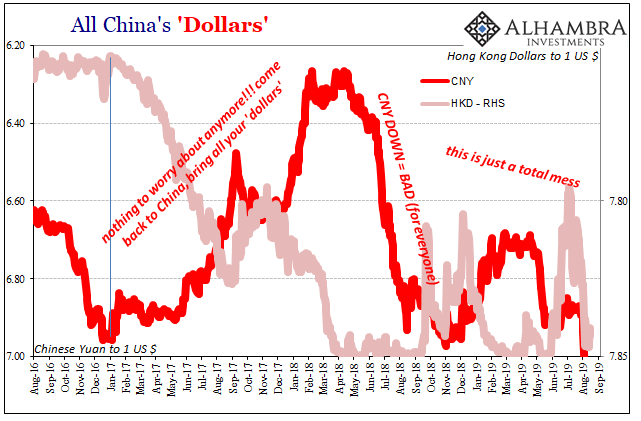

What it all suggests is that Japan might not any longer be so crucial to China’s ongoing “dollar” problem. In its place, at the margins, Hong Kong banks appear to have been substituted for Japanese firms. From the Chinese perspective, you can, I hope, understand why as well as the difference. Hong Kong may own a separate currency/monetary system, but it is still China. And the latter’s global monetary reputation made it, apparently, too tempting to resist two decades of promises not to intermingle.

Even then it seemed pretty clear what had happened. Risk rules the eurodollar system. Following the 2011 crisis and then the global 2012 slowdown, China became (further) entangled in the same monetary sickness as everyone else. By the middle of 2013, the negative effects were more and more certain.

Higher perceived risk means fewer dollars which then leads to economic problems confirming the perceptions. And round and round it goes, unless and until something breaks the cycle. The 2016 fiscal and monetary attempts wouldn’t have broken it, only temporarily suspended it. CNY was the key.

To deal with perceived higher risk, China stood Hong Kong out in front – eurodollar banks weren’t lending “dollars” to China, they were bypassing the perceptions by having them lend to the pristine reputation of Hong Kong. How and why those “dollars” were ultimately used wasn’t supposed to matter. Bring all your dollars back!

For all the complexity and gamesmanship, the real crux of the matter is that it didn’t work. The “dollars” didn’t come back, at least not in the way officials must have been hoping. China’s economy never really got that far off the ground, fostering the prime conditions for the next wave of negatives.

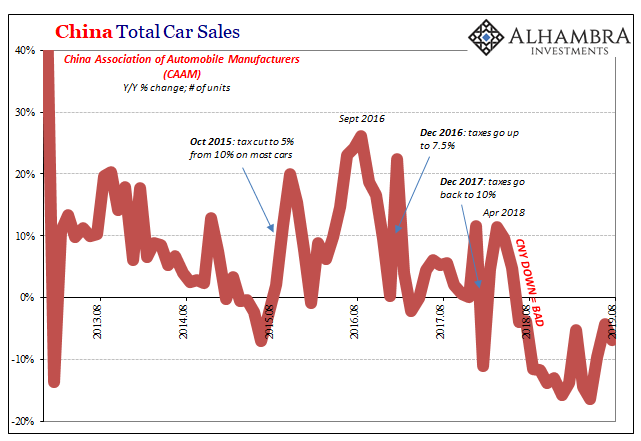

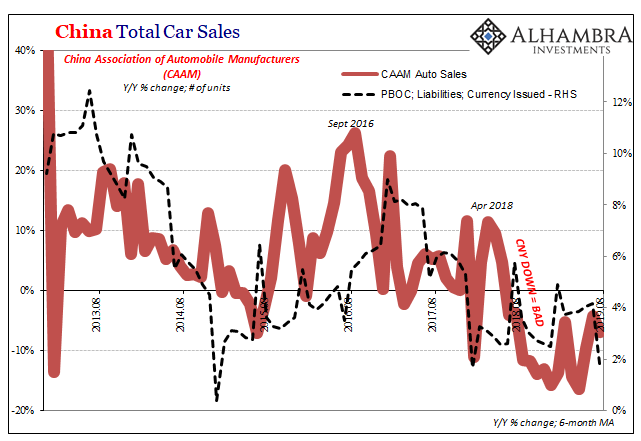

That next wave, Euro$ #4, is now beginning to crest, and in a lot of ways it looks to be worse than the last one four years ago. In economic terms, China’s automobile sector is one such prime example. Nothing so much marks the country’s massive transformation so much as its glittering new cities stuffed with cars and trucks.

You look back at some of the old television footage of news stories about Chinese cities and it is remarkable how everyone in them was riding around on bicycles. Once China was opened up, and dollarized, the car steadily replaced the bike; a trend observable in every wealthy and transitioning society in modern industrial experience.

But in 2018, that all took a step backward. For the first time since bicycles predominated, auto sales contracted last year. Worse for China and whatever might be left of globally synchronized growth, it’s not getting any better in 2019. Sales are going to contract again and by an even greater amount.

The relationships between not just auto sales and domestic money but more broadly global economic trends and global money are obvious. The whims of the eurodollar, its general behavior directs these worldwide cross currents. Having never recovered from what was Euro$ #3, China is heading down deeper into Euro$ #4 – automobiles first.

To try to offset the painful monetary influence, there will be still another RRR cut next week and quite predictably Chinese authorities are extending their kindest and warmest regards to anyone with dollars who might want to invest them in the country. Having maxed out Hong Kong, what else is left?

China removed one more hurdle for foreign investment into its capital markets almost 20 years after it first allowed access…

It’s the latest push by Chinese authorities to increase use of the yuan in international transactions, and comes as they seek out more foreign capital to balance payments. Scrapping the investment quota is also another step in policy makers’ efforts to open up China’s financial system to the world.

Yeah, no. This has nothing to do with “increase use of the yuan”; that’s just what the government says. It is, like everything, couched as if a friendly Communist regime remains committed to market reforms and opening up for its own sake rather than what this really is – please, please bring us all your dollars, we’ll remove as much headache as possible so that nothing, absolutely nothing can stand in your way of delivering them to us.

As noted not that long ago, the more China accelerates these “reforms” they are telling you the bigger their dollar problem must be. Which is of no surprise.

The only thing that wins here is when something breaks the dollar (shortage) cycle. That can only realistically mean the eurodollar system itself. What the 19th Communist Party Congress effectively admitted was how Communist government authorities didn’t think it was going to happen; 2017 was a temporary gap, not a permanent displacement. They would prepare China for the consequences of the latter.

That’s doesn’t mean they won’t still try, but by and large that’s just what we’ve seen over the nearly two years since that Congress was held (and still curiously without a 4th Plenary Session). The rest of the world was giddy about growth and inflation. China was immensely concerned about a nastier number four.

It seems that they were right to be. Follow the bid(s) for dollars.

Stay In Touch