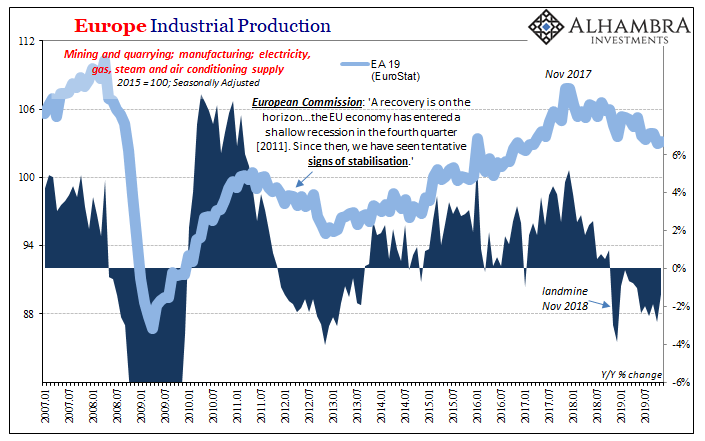

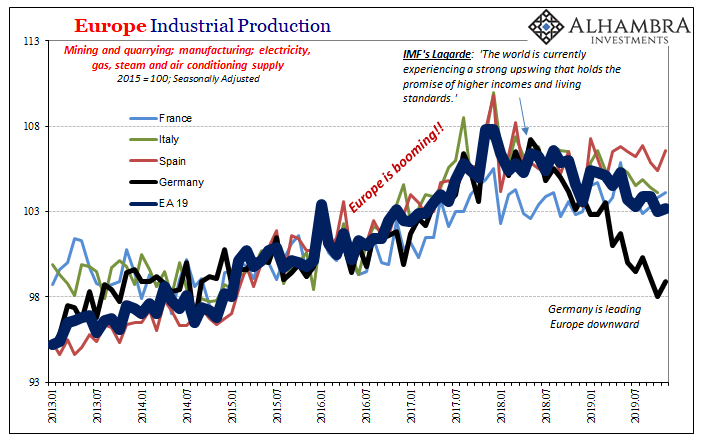

For anyone thinking the global economy is turning around, it’s not the kind of thing you want to hear. Germany has been Ground Zero for this globally synchronized downturn. That’s where it began, meaning first showed up, all the way back at the start of 2018. Ever since, the German economy has been pulling Europe down into the economic abyss along with it, being ahead of the curve in signaling what was to come for the whole rest of the global economy.

The ECB, many complained, had panicked in Mario Draghi’s final act. Another QE that critics charged was unnecessary. Draghi, though, being stung by the “unexpected” decline warned that it shouldn’t be taken so lightly. Protracted was the word he specifically used.

And it’s interesting the contradiction of sorts created by Draghi. He said QE was necessary because weakness was more stubborn than anyone, any official, anyway, had anticipated, but in doing QE he provided a basis for growing optimistic sentiment. QE was necessary because the downside was serious and stubborn, but those in favor of it now think the weakness was easily overcome by another bond buying program?

This is, as I’ve pointed out before, not unusual. It happens every time like clockwork. No matter how lengthy the catalog of empirical evidence that shows QE and monetary policies in general, especially of the “non standard” variety, don’t work they’ll line up to praise its positive effects before its even launched.

It begins the way it’s being told right now; the economy has stabilized and that is the first step toward renewed growth.

You can pick any number of prior examples (and not just in Europe). I’ll provide one here written by the European Commission in the spring of 2012. Europe had in the year before, like in the year 2019, experienced an “unexpected” decline which was met with “powerful” “stimulus” then in the form of non-standard LTRO’s. Money printing, they said. Trillions.

The first LTRO was auctioned in December 2011. A few months later, the European “government’s” Economists said:

A recovery is on the horizon, but it will be a long and stony road before the EU economy reaches sustained growth. Following the escalation of the sovereign-debt crisis in the second half of 2011, the EU economy has entered a shallow recession in the fourth quarter. Since then, we have seen tentative signs of stabilisation.

They no doubt saw signs of stabilization but they weren’t real, or the right ones. Monetary policies have a special way of making Economists warm up to any situation.

For the record, the European economy’s weakness would be protracted in 2012 and 2013, too, with the worst of that recession coming right after the issue of the report quoted above.

Thinking about stabilization in Europe again in 2020, Dieter Kempf poured cold water all over it earlier today. Who is Mr. Kempf? He’s the President of Germany’s influential Bundesverband der Deutschen Industrie (BDI). QE was relaunched more than four months ago, and yet Kempf says:

Industry remains stuck in recession, there are no signs for the sector bottoming out.

So, either QE works for the rest of Europe just not Germany, or the way forward is still written in German and that continues to be the wrong direction. The consistent result of QE.

Evidence for the latter, EuroStat also reported earlier today estimates for European Industrial Production. Seasonally-adjusted, it was up ever so slightly in November 2019 from October if only because October’s figure was revised downward to the lowest level since early 2017.

Year-over-year, industry at least across all of Europe continues to decline at a rate equal to that of the lowest during the 2012 recession.

Perhaps most importantly, you can plainly see how it is German weakness that is setting Europe’s marginal economic course.

Interesting, then, that Mario Draghi’s final act may have been correct. Not what he did, QE, but why he did it. Protracted weakness indeed.

Stay In Touch