Forget about trade wars, or even the eurodollar’s ever-present squeeze on China’s monetary system. For the Communist Chinese government, its first priority has been changed by unforeseen circumstances. At the worst possible time, food prices are skyrocketing.

A country’s population will sit still for a great many injustices. From economic decay to corruption and rising authoritarianism, the line between back alley grumbling and open rebellion is usually a thick one. But you put food problems on the table and all bets are off.

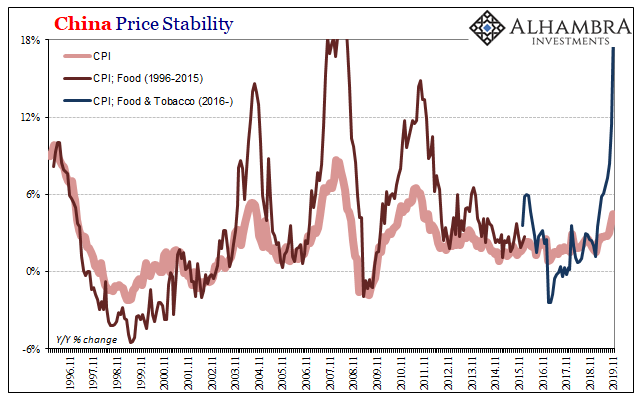

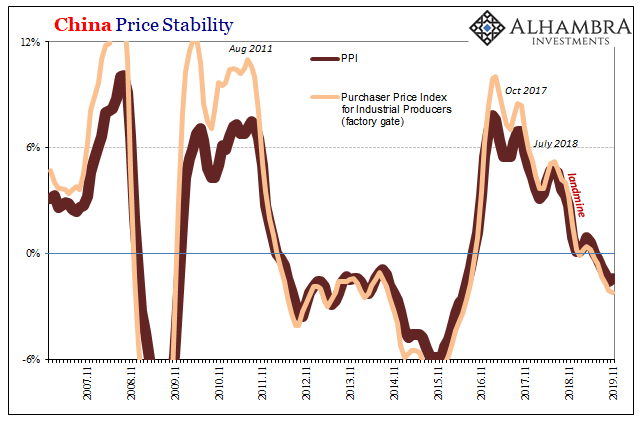

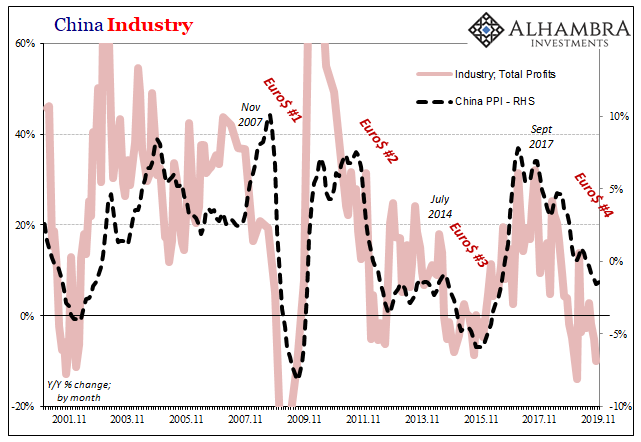

The economy continues to slow down – that’s what Chinese producer and factory prices are telling us. As it does, food prices have gone off the charts. Other than total economic collapse, pork supply problems are the surest way to make China’s current situation feel unbearable.

It started in August 2018, when African swine fever was first detected and announced. It may have been running around rural areas for some time before then. Since, China’s hog herd has been decimated, both due to the disease as well as the government ordering various farm stocks destroyed in a vain effort to slow the spread of the disease.

The size of the aggregate hog herd in China had been reduced by about a third in November 2019 when compared to November 2018. As a result, pork prices were up by 110.2%. As struggling Chinese families sought alternatives, beef prices had jumped by more than 22% (and lamb up 14%).

The overall basket of food prices in the Chinese CPI accelerated to a 19% year-over-year increase last month, closing in on record territory. It is a new high no country ever wants to see in its data.

Outside of pork, consumer prices are an entirely different story. The overall CPI surged by 4.5% because of it, but excluding food and energy consumer prices were up just 1.4%.

The reason for the disparity is quite simple: China’s economy continues to slow and now consumer prices have added an enormous, local “headwind” to the trend. The Chinese PPI is a perfect illustration. It was down yet again in November, falling 1.4% year-over-year.

While that is a slight improvement from October’s -1.6%, factory gate prices (prices of industrial purchasers) continued to trend further downward; -2.2% in November as compared to -2.1% the month before. China’s producer and factory purchaser prices correlate closely with industrial profits – another leading indicator for the Chinese economy.

In other words, ongoing discounting as further economic slack develops across China’s monstrous industrial sector.

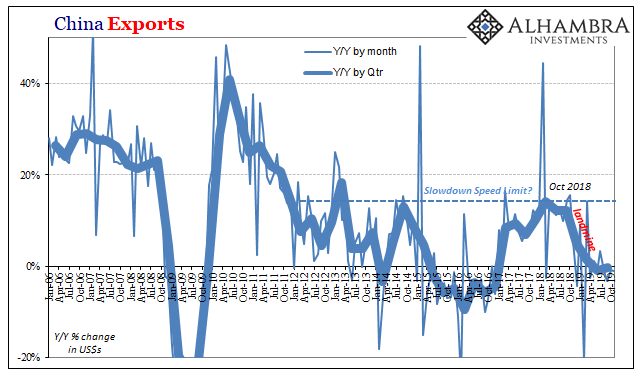

And that sector can’t get back on track because there still isn’t any external push. Global trade continues as depressed, leaving Chinese exports to another small contraction also in November. Down by 1.1% year-over-year last month, it was the fourth consecutive negative number, and five out of the last six months, even if each one was comparatively small.

A small negative number for exports is an enormous, underappreciated negative pressure.

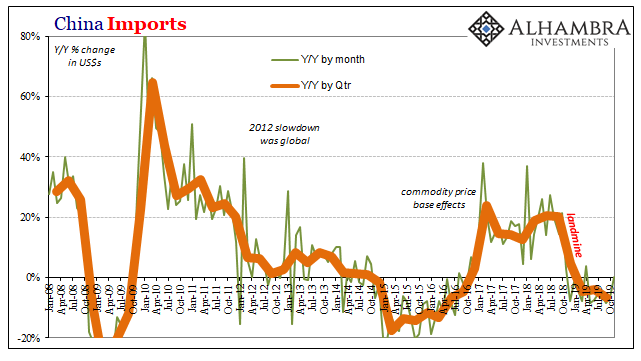

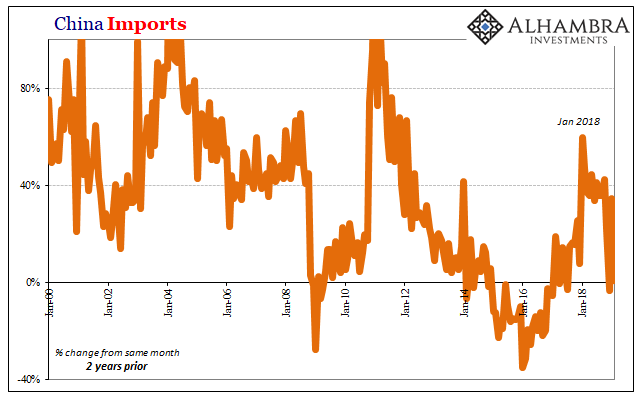

Without much to gain from external demand, internal demand further squeezed by relentless monetary compression is practically non-existent. Chinese imports last month were essentially unchanged from the year before, therefore a good illustration for how little China’s economic demand has changed since last year’s landmine.

While it was the first technically positive number (+0.3%) since May, and a small increase from October’s -6.4%, November 2019 is also being compared to November 2018 which was the first month on the ride down into the landmine. Imports last November (2018) had risen only 3% from the November before that (2017).

Though imports in October 2019 were down 6.4%, in October 2018 they had been up by more than 21%. The two-year change really tells the global story, including how everything seems to have peaked…once again in January 2018.

Persistent if slow deceleration in the economy now combines with rapidly accelerating meat prices. The question now is, what does the government do about it?

On the narrow problem of pigs, authorities are greatly expanding their efforts. Being an outside observer, however, it is difficult if not impossible to determine just how much is window dressing; the appearance of doing things so as to try and placate an uneasy population.

The Communist State Council has moved to validate local province price subsidies (available in 29 of them so far), thereby opening the door for more intensive and uniform aid across all of China. It also announced recently more efforts to curb the disease, though there weren’t many specifics about how that might be done better (or at all). And the Council also said it would allow new measures to speed up restoration of the cumulative pig stock.

That may mean even more hog imports, too.

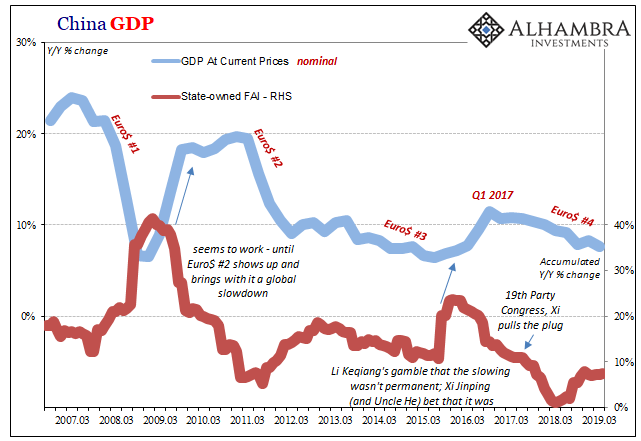

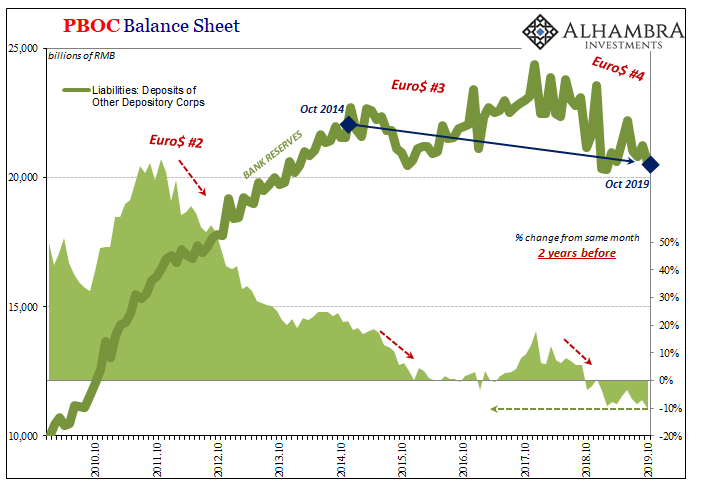

The big question is whether this dangerous combination forces Xi Jinping and Liu He to move more than a little bit off of their “managed decline” strategy. To this point, the government has been sidelined from deploying its usual Keynesian textbook approach, once advocated by sidelined Premier Li Keqiang.

And that might’ve been the biggest downside surprise late last year – many by November 2018 had come to expect that given the way China’s economy was speeding up in the wrong direction authorities would announce how in January 2019 (the government does everything by calendar year) they would redo what was done in January 2016.

Instead, Xi’s preferred approach has been consistently to try and limit the growth downside as much as possible (you can see it above, the very small increase in SOE FAI early in 2019).

Part of the recent global trend moving toward a more optimistic view similarly rests on China changing its approach. It is becoming more widely expected that if Xi hadn’t been convinced in November 2018 to act by January 2019, what’s happened this year with further slowing growth and now widespread, serious food price problems that already in November 2019 the decision may already have been made to ramp things up in January 2020.

If that was the case, however, it seems very likely such a decision would’ve shown up across-the-board in especially commodity prices (meaning a sharp increase, rather than the current meandering midpoint). In other words, it seems many, in light of these growing internal pressures, are hoping such a stimulus verdict has been reached in the absence of any evidence it has.

Such hopes, however, rest upon a misunderstanding of both the true nature of the country’s affliction as well as what it has meant for China’s underlying condition (a zero-growth world).

The only part that is certain to be ramping up right now are those combining negative pressures.

Stay In Touch