Chairman Powell’s hawkishness, so called, has made its way into the historical revisions for Personal Income estimates. The Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) released today the annual benchmark revisions to NIPA, the National Income and Product Accounts, which apply to Personal Income and Personal Spending. We’ve already seen the results for GDP and underlying data for corporate profits.

What the BEA discovered was more income. A whole lot more. At first glance, this seems like a really good thing. After all, figuring there was more income received by the personal sector, how can that be bad?

It isn’t a bad thing; the data does, however, make a huge mess of the situation.

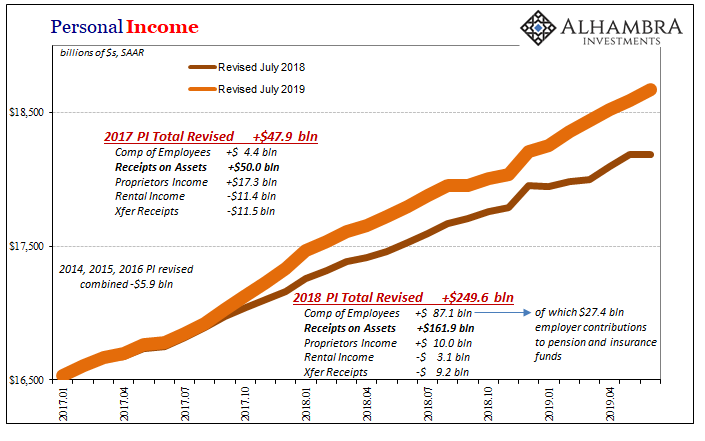

The benchmark revisions applied only to the years 2014, 2015, 2016, 2017, and 2018. Of those, there weren’t any meaningful changes in the first three. Nearly all of the revisions register from late 2017 forward (shown below).

Starting at the very top, total Personal Income, the changes are substantial particularly for 2018. Combined 2017 and 2018, the BEA estimates nearly $300 billion more in personal income. Again, that’s not a bad thing.

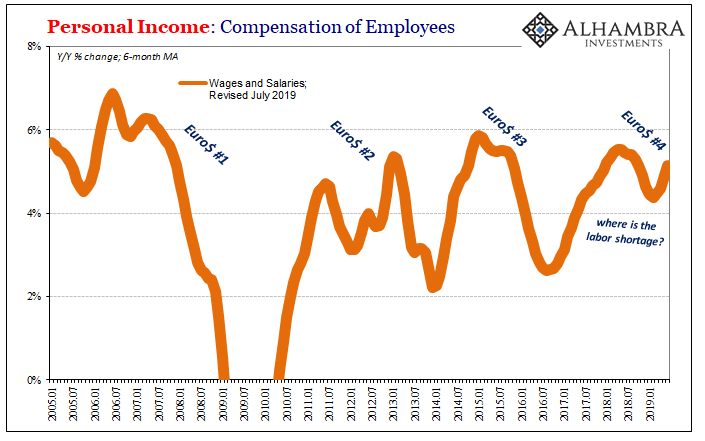

Even though this coincides with inflation hysteria and the constant shouts of LABOR SHORTAGE!!!, it wasn’t employers paying a lot more to procure and maintain employees. Of the $297.5 billion gained by the revisions, almost three-quarters of it pertained to Receipts on Assets – dividends and, yes, interest.

In other words, there’s much more of the BOND ROUT!!! in these figures than the LABOR SHORTAGE!!! (which is pretty darn ironic). This isn’t to say wages and salaries weren’t revised higher, which is exactly what this economy really needs(ed), they were. But it was far less of the overall number, which makes for more noise than straightforward analysis.

By benchmark, the data is a muddle as the new Personal Income numbers filter down into their constituent categories.

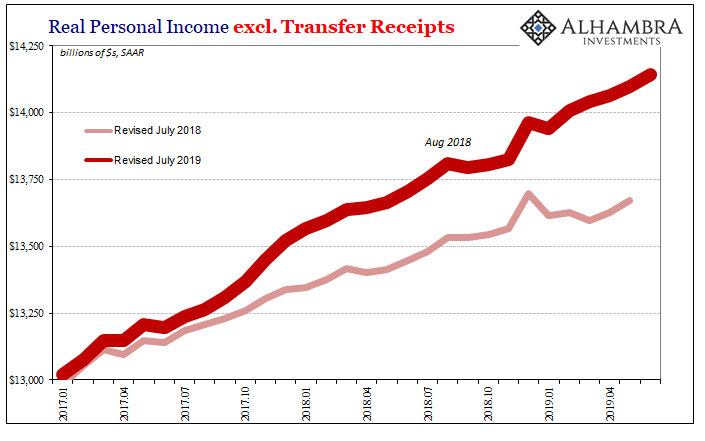

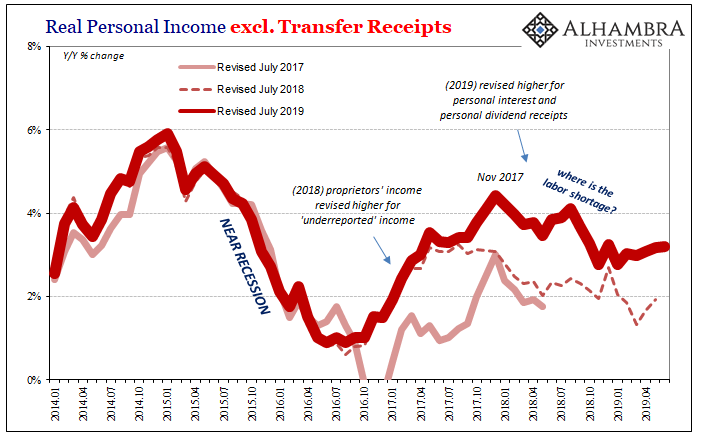

Real Personal Income excluding Transfer Receipts now has a higher high in the most recent reflation cycle (with now a more noticeable top or peak at November 2017; there’s that month again) but still a decelerating trajectory which is now cushioned to a large extent by higher interest and dividends rather than earned income.

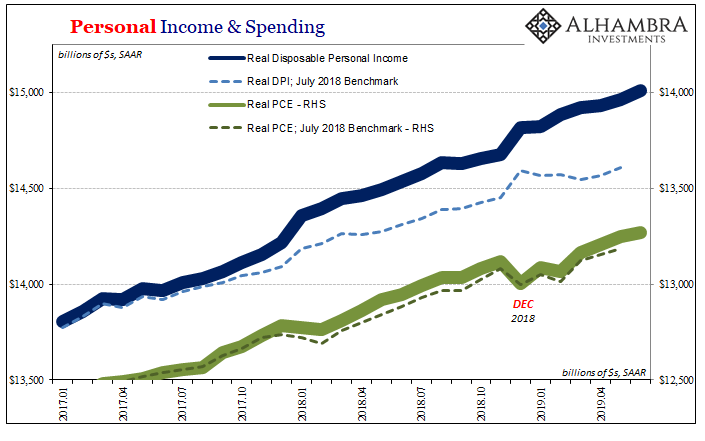

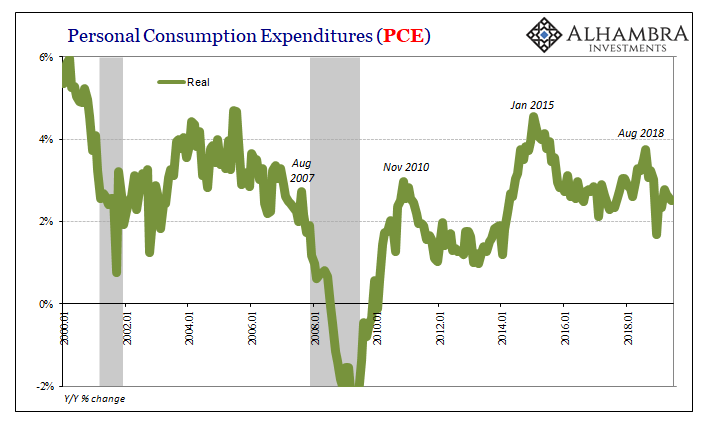

That’s why Real Personal Consumption Expenditures (PCE) were revised only slightly higher. Though incomes are significantly better than thought, because it was primarily receipts on assets the greater receipts weren’t widely distributed. The revised figures don’t suggest labor income was so much better, therefore estimates on spending are practically unchanged.

Spending growth is back to averaging what it had been at the bottom of the near recession of Euro$ #3. Even though income growth overall is substantially more than thought, because it isn’t the LABOR SHORTAGE!!! showing up in the BEA accounts the downturn in consumer spending remains in the new data.

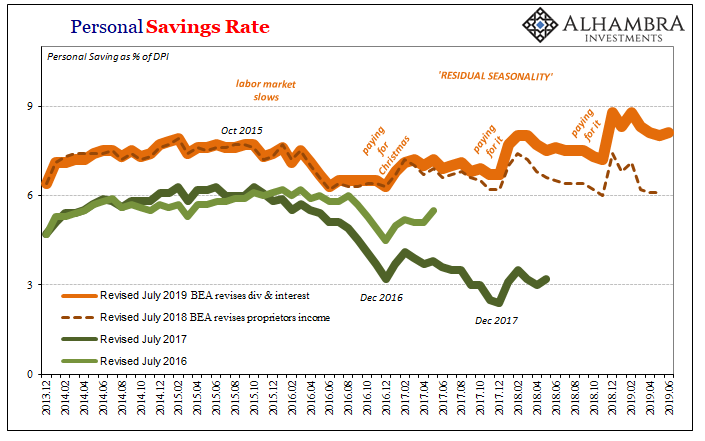

Give those disparities revisions to reality, the Personal Savings Rate is once again completely different at this benchmark compared to any of the prior three. In fact, the savings rate is all over the place each and every time the NIPA tables go through their annual update.

The reliability of the series is in doubt – which raises other unrelated questions about why that could be. Might the BEA be having so much trouble because this economy is so unlike how the economy performed prior to, say, 2008? That’s a serious question for some other day.

What stands out isn’t the revisions to income, it is rather the residual seasonality which remains regardless of the data series. Consumers are still struggling around the Christmas holiday. They quite naturally splurge and then have significant difficulties paying the bill early in the following year.

No matter how much or how far the BEA tinkers with the income numbers, or for what reasons, no matter how low the unemployment rate falls, this residual seasonality continues to be highly conspicuous. That’s simply because no matter what the government cannot locate the LABOR SHORTAGE!!!

It seems like they’ve found everything but. Business and asset owners have done better the past few years, and that’s good. But that’s not the economy of the unemployment rate.

Rather than clarify where things stand, the new figures which are more accurate leave us asking more questions. What we are left with after these revisions is still the slowing economy, but not as clear of a picture about how much it has slowed, from what level it may have begun the decent, and whether or not interest and dividends make any difference.

The savings rate, for example, got up near 9% (like it was 1977 all over again) during the landmine in December 2018 (when residual seasonality started early). It was only 7.4% under the prior benchmark before the BEA refigured Receipts on Assets. Is there a meaningful difference between them in macro terms? It could be a good thing that asset owners are saving more of the income they receive, but ultimately it may not matter if despite more interest and dividends the vast majority of consumers pulled back (a little) on spending.

The economy is clearly not falling off a cliff. What concerns policymakers is that other parts of the global economy are either already acquainted with the cliff or are in sight of it. The fact that the US economy is slowing puts it on the same ground as those others – therefore the rate cuts – but further behind in the process.

The revisions in income make it harder to assess how far back from the edge the domestic economy actually is, and how resilient it might be in being able to stay far back from its boundary. It depends on how you factor dividends and interest – especially balanced against corporate profits, which in their revisions went the complete opposite way.

Stay In Touch