It was a tense exchange. When even politicians can sense that there’s trouble brewing, there really is trouble brewing. Typically the last to figure these things out, if parliamentarians are up in arms it already isn’t good, to put it mildly. Well, not quite the last to know, there are always central bankers faithfully pulling up the rear of recognizing disappointing reality.

At the end of November, Mario Draghi went before Europe’s “parliament” to defend Europe’s central “bank” (since I’m purposefully using quotes here). He was hit with all sorts of questions about ending QE, many politicians urging him to reconsider terminating the program.

If Ben Bernanke had taper in 2013, Draghi has been subjected to weaning. Most of those questioning the ECB’s timing have been concerned about obvious slowing and weakening. No one ever bothered to ask the central bank president how if QE was effective the economy could be slowing and weakening. The two don’t go together.

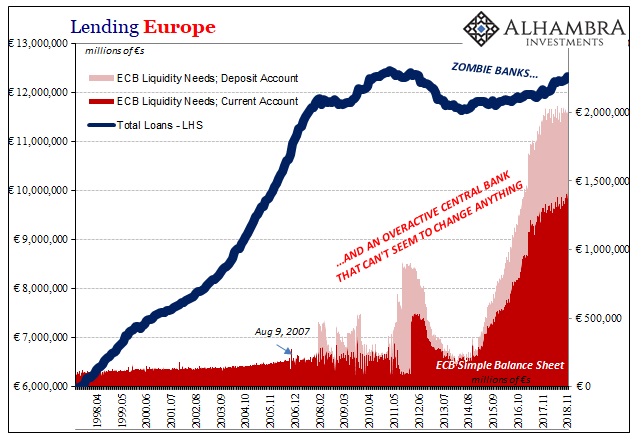

Draghi, of course, knows this. He betrays in public the required stoic figure, but there were several moments in Brussels last November when his poker face abandoned him for a more emotional posture. Gerolf Annemans, a parliamentarian from the Belgian delegation, accused Draghi of hurting banks (it has) and stoking asset bubbles (it hasn’t, except through sentiment in stocks). “For me, this is a policy which has had disastrous consequences,” Annemans charged.

To which Draghi passionately replied:

Our policy had disastrous consequences? Yes, it created 9.5 million jobs in a few years.

QE did all that? Even if it did, nobody followed up to call Draghi’s bluff. Is 9.5 million even a lot of jobs “in a few years?” No, no it isn’t. That’s the conceit, the fear everyone has over speaking factually. Nine and a half million sounds like an enormous number, the central bank weapon of choice in dearth of actual evidence.

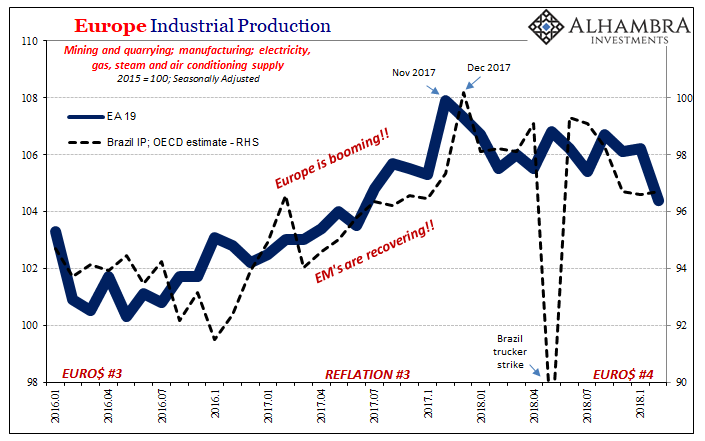

Therefore, Draghi’s QE story remains intact narrative-wise. QE brought about a strong European economy, so if it is slowing toward the end of 2018 it is doing so from an unusually good place. No big deal, no contradiction.

Once you realize none of that is true, as I think Draghi himself privately worries, QE falls back under robust suspicion. The things people are talking about that are supposedly causing this economic uncertainty are not the kinds of things that would cause any problem whatsoever if Europe’s economy had truly boomed. Trade concerns are at the top of every list.

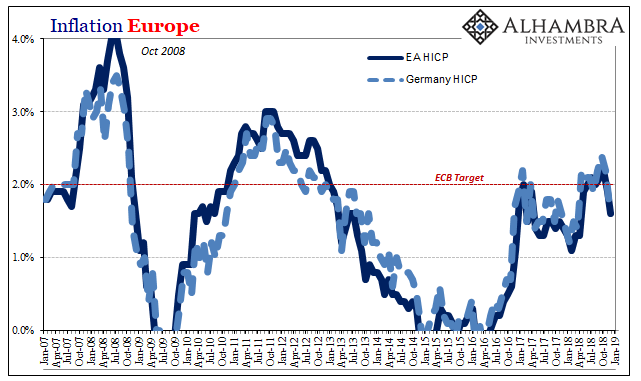

Germany today reports that consumer prices in January 2019 rose 1.7% year-over-year, preliminary estimates harmonized to the Continental method for figuring inflation. That holds steady from the same rate in December, now two months running below the ECB target after six out of the past seven months a bit above the policy goal. The local CPI rose just 1.4% this month, the weakest in over a year.

German inflation held steady in January amid a significant deterioration in the economic outlook, adding to the challenges the European Central Bank faces in weaning the euro area off unprecedented stimulus.

Weaning! Draghi also knows that inflation is now directly undercutting him. The key to success for any monetary policy is not the occasional, temporary period of just barely touching 2%. He must bring consumer price inflation up to that level and then keep it there.

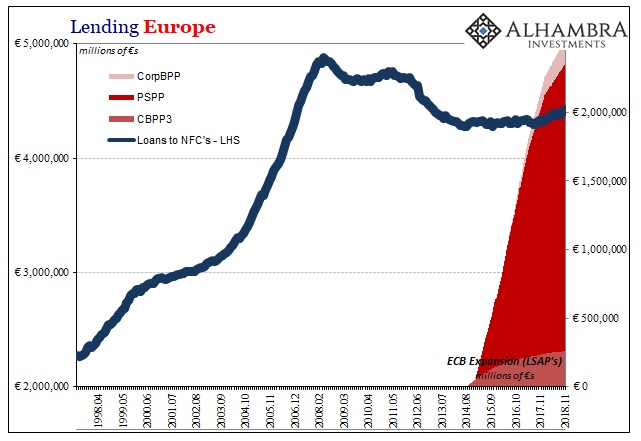

The only way to do that is if the economy actually performs. If it doesn’t, then something remains wrong. QE couldn’t have been successful; it was instead downright Japanese. Meaning irrelevant.

The two fit perfectly together: a strangely weakening economy for reasons that shouldn’t matter if 9.5 million was a good number and downbeat inflationary numbers confirming the lack of QE follow-through where it was supposed to work most directly.

What happened in 2017 was simply the overhyping of the positive numbers particularly under the framework of “global growth”, synchronized in this updated case. Europe’s internal economy was supported by that rather than QE. Thus, as “global growth” curiously disappears, so too does Europe’s.

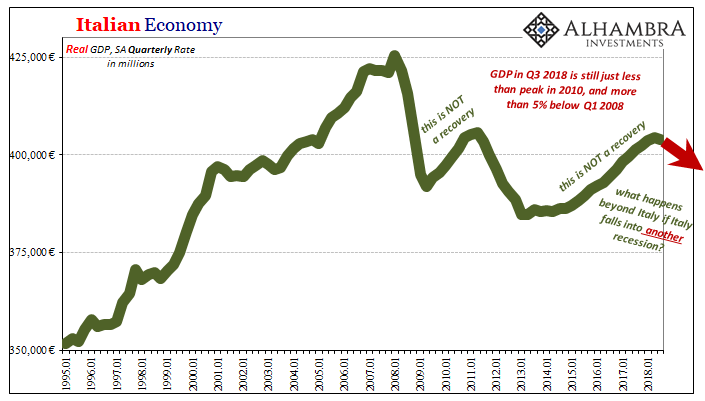

Again, this is not how it’s supposed to work – at least according to the narrative spoken in public by Mario Draghi. The rest of this week should fill out that picture. Germany and Italy will report initial estimates for GDP in Q4 2018, the former expected to eek out a small positive but at risk of a second minus in a row that fulfills the so-called technical definition of recession. Italian GDP, by all counts, is all but certain to do just that regardless.

Economists supported by Draghi’s staunch optimism are getting worried, too. Here’s ING Economist Peter Vanden Houte speaking today as Eurozone confidence falls to multi-year lows.

At this point, we think the risk of a recession this year still remains low, unless all downward risks materialize.

Yes, the risk of recession remains low…unless a recession materializes. Not a whole lot of confidence (nor logic) on display in making such a statement. If QE had been at all mildly effective, the withdrawal of support from “global growth” wouldn’t have mattered to a European economy left undeterred by its own internally consistent virtuous circle of idiosyncratic economic factors. It’s at risk of recession because that never happened.

But that’s the real truth of the matter. Europe can’t be left alone because it is a global system. As it goes, everyone follows central bank or not. This is why, in general terms, QE is irrelevant wherever it is attempted. The global economy is trending toward downturn, which means the global economy is trending toward downturn.

Recession isn’t even the real issue; it’s the prospect for another one because of that global economy having never recovered from the last few (just ask the Italians). QE therefore like Japan only means doing this same thing over and over again. Nine and a half million doesn’t make a recovery, it writes a recovery fiction.

Stay In Touch