What is the Greenspan or Fed put? It is an idea, the legend that says the US central bank will only allow a little downside in stocks. The 1929 crash despite being so long ago has been indelibly imprinted upon the machinations of policymakers. Some say they can’t see a big slide without the Great Depression.

Therefore, they will do anything and everything to prevent a market crash; up to and including, pace 2002 Bernanke, using the “printing press.” Since money goes into stocks, a la 1929, monetary policy is a key factor in stock price bulges.

Almost none of that is true, however. The only part that is correct is the FOMC’s fixation on the S&P 500. They talk about the market all the time, but more as an information tool than anything else. Since bubbles, they’ve noticed stretched valuations but more often than not they are rather pleased with what they think exuberant share prices say about their own work.

It’s circular reasoning at its worst; stock prices are up because the economy is doing well, and we know the economy is doing well because stock prices are up. Congratulations [insert the name of the current Chairman here]!

The links between money and the floor of the NYSE were severed a very, very long time ago just after the Great Crash (there is no such thing as call money anymore). While the image of 1929 lingers ever onward in our collected fears, the Crash of ’87 is by sharp contrast a minor footnote for a reason.

In the 401k era, equities are a portfolio class that is built up and nurtured by personal savings. In the 21st century, share prices are pushed further by another form of savings, corporate profits deployed via repurchases.

The Greenspan put nowadays is better classified as the CEO-pay put.

In truth, there is more Keynes than Bernanke or Powell at work. John Maynard once said markets can stay irrational longer than you can stay solvent. That’s not quite right, though, not in this modern context. Markets can rationalize longer than you can solvent, often doing so in large part because of this one myth.

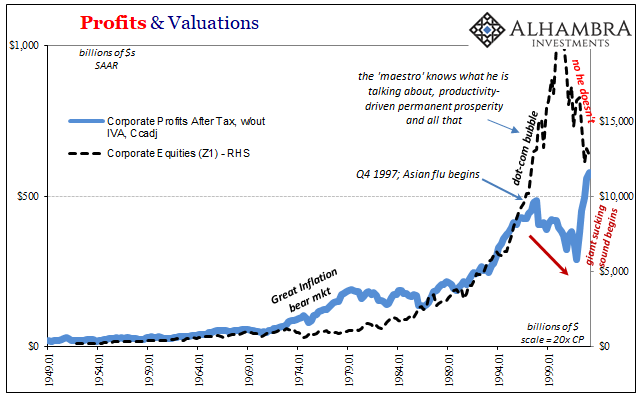

Valuations in markets have been stretched three times over the last two decades, two of those fairly classified as bonafide stock bubbles. Every one of them aligns closely with rationalizations about the Federal Reserve and monetary policy.

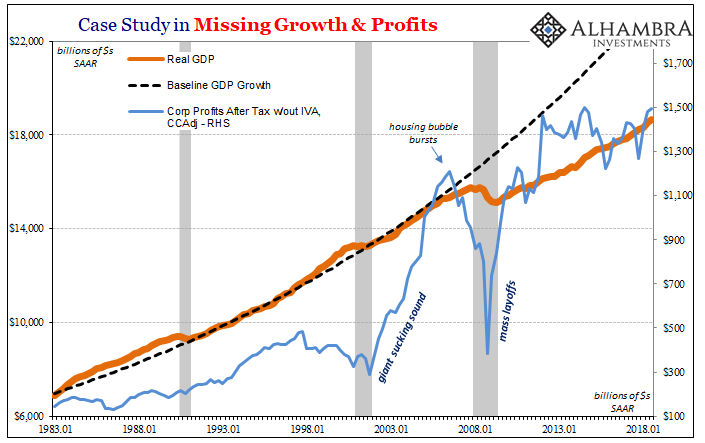

Different profit proxies put a different face on each episode, but by and large the overall picture is the same. The Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA), the government agency responsible for tabulating GDP, also estimates corporate profits as part of its data on economic output. According to their figures, corporate profits in 1998 began to fall even as share prices (using separate data from the Federal Reserve, the Z1 or Financial Accounts of the United States) skyrocketed.

It was during this time the idea of the Greenspan put was born, taken from the belief that the FOMC moving around the federal funds rate a quarter point here or there was a powerful economic input; more than that, Greenspan was a genius and therefore knew both what to do and how to do it.

In the context of the late nineties, that meant falling profits (or more slowly rising, if you use other data such as net income stats for the S&P 500). Investors rationalized that divergence in several ways, mostly as a combination of the times (radical economic change through technological progress that would lead to greater prosperity over time) and Greenspan (he’s the guy who can buy the economy sufficient time with his federal funds lever so it can achieve its dot-com potential).

The Asian flu was not followed by a new economy of permanent prosperity but the dot-com bust and recession. Both caught Greenspan off guard, so much for his “put” and the power of federal funds “stimulus.”

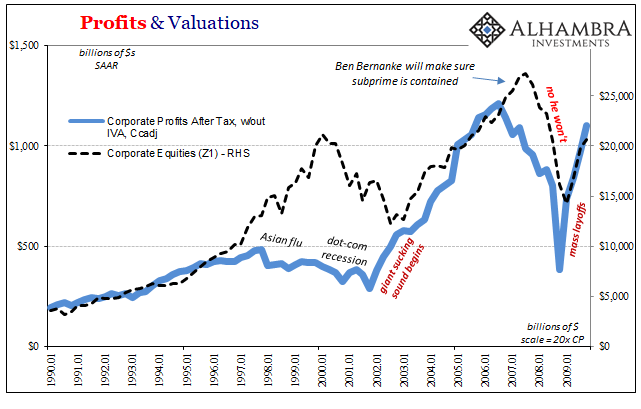

This was followed by the housing bubble (of eurodollar fame) when stocks hadn’t strayed nearly so far from corporate earnings. But in 2006 there was trouble again; profits began falling like they had in 1998. For over a year, increasing turmoil was rationalized in the same way, now a Bernanke put.

The discrepancy didn’t last nearly as long as the rationalization mania during the nineties because let’s face it the latter part of 2007 left little doubt about subprime being contained (or that it was even about subprime at all). The Bernanke put proved just as worthless as the Greenspan put; stocks crashed a second time, the economy even worse.

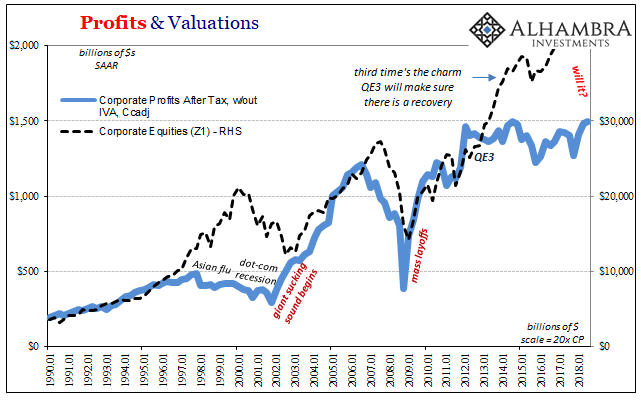

Here we are again, now with a different kind of Bernanke fable more along the lines of a QE put. Again, people want to believe monetary policy is powerful and in the case of QE actual money printing. That doesn’t mean the inert byproduct of bank reserves ended up at banks buying stocks (it didn’t), but enough people thought that’s what was going to happen (the Fed only too happen to stay silent as to the error) while most of the rest just believed it would work saving the economy and starting recovery.

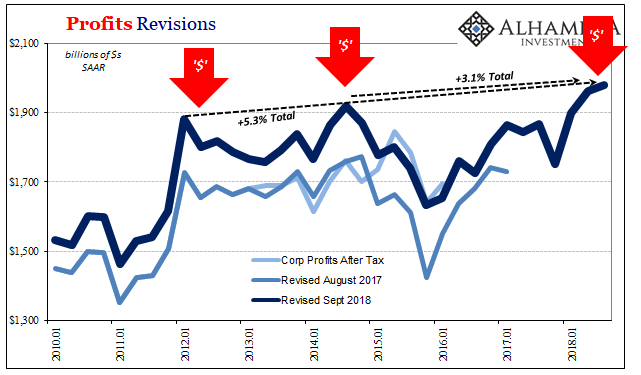

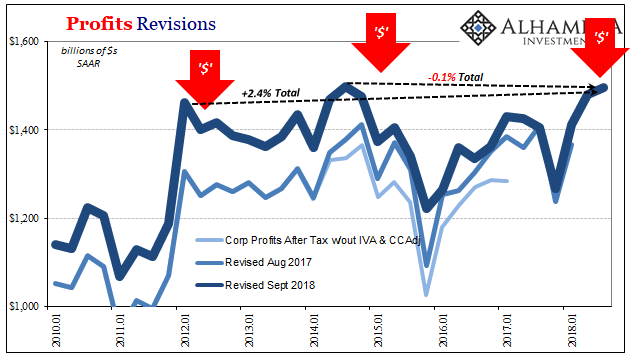

As of the latest profit statistics, released today, the BEA numbers add to the mountain of evidence conclusively establishing that it never did. Not even in the short-run. There is much more eurodollar than QE in these figures.

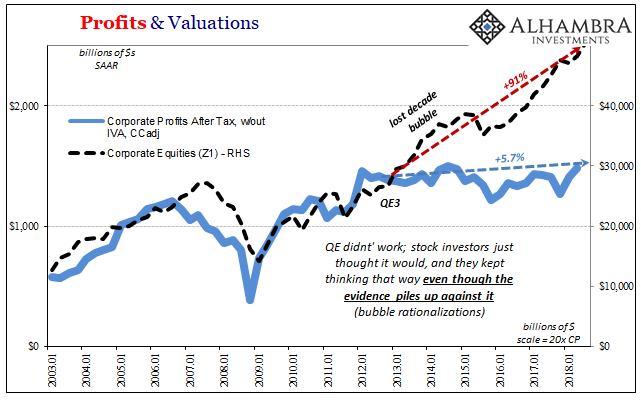

Since the quarter in which QE3 was launched, the same one a fourth QE was added, the overall market value of equities according to Z1 has surged by 91%. Over those same 23 quarters, almost six years, profits are up by less than 6% (total, not per year).

This has taken the late nineties level of rationalization to its extreme. One reason for that is surely because of the muddied nature of the current economy. People keep saying it is booming, that QE did work, and the unemployment rate sure seems to suggest as much. The unemployment rate is itself a separate layer of rationalization, one that is only now being subjected to closer scrutiny.

Where’s the wage-driven inflation, Mr. Powell?

The QE put was self-delusion about an extreme form of the same magic trick. There really wasn’t any difference between Greenspan’s 25 bps monkeying and Bernanke’s trillions in LSAP’s. There is a no comparison between monetary policy with money in it (which doesn’t exist today) and expectations policy which leads everyone, and counts on everyone, to just believe there is.

Stock investors put their savings where the Fed’s money isn’t.

Stocks have been bid as if QE was going to be effective given enough time. Even after 2015-16, Yellen’s contribution of “transitory” stuck. Time itself was the key in this bubble. The question now, with all that’s going on as 2018 ends in chaos, has time run out on the already twice-disproved put? Or, can rationalizations push for another few years?

The only part being cleared up right now is the likelihood of corporate earnings joining share prices at such lofty levels as everyone has been waiting on; that probability sinks with each wave of renewed eurodollar nastiness.

Stay In Touch