This is perhaps the perfect day to review what’s going on in Hong Kong (thanks J. Fraser). I’ll be in Vancouver over the weekend to talk about curves, so why not preface it with a little HKD update. With everyone focused elsewhere, the story of 2017, in my view, wasn’t so big in 2018. For reasons that will further disturb Economics convention the city is making a comeback in 2019 (really last December).

This is what happened today:

A string of Hong Kong-listed stocks plunged without warning in afternoon trading, the latest shock losses to sideswipe investors in the world’s fourth-largest equity market.

Jiayuan International Group Ltd., Sunshine 100 China Holdings Ltd. and Rentian Technology Holdings Ltd. fell over 75 percent in a matter of minutes and at least 10 companies were 20 percent lower or more by the close, wiping out HK$37.4 billion ($4.8 billion) in market value.

Though these things do take place from time to time, this wasn’t a flash crash in the same way as prior events. The share prices of these companies and others fell quickly enough, but didn’t recover. It seems as if HK is a little lacking on the liquidity side.

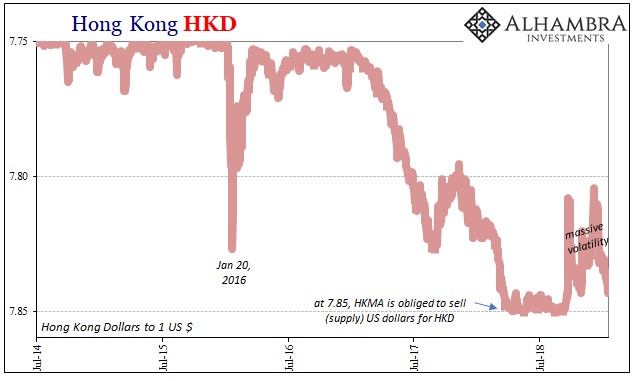

In relation to that, monetary authorities there had promised that the sinking HKD early on last year was nothing to be concerned about. The world had parked massive liquidity in the city’s financial system in 2009 in the aftermath of global panic. Now, as the world of 2017 was inching closer to normal and recovery, that money was leaving the safety of Hong Kong for riskier ventures in globally synchronized growth. Allegedly.

This was the stated theory behind HKD’s falling exchange value as well as rising interest rates (HIBOR) in interbank HKD markets.

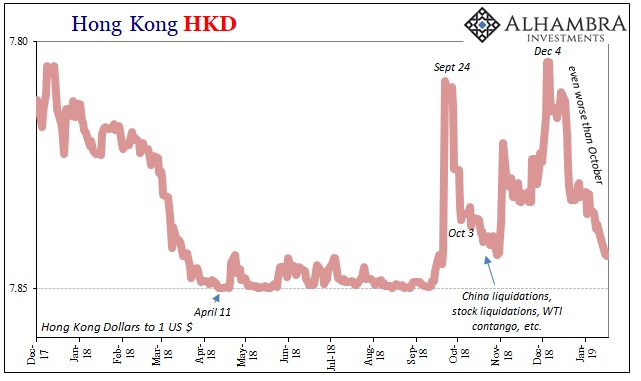

Yet, no one would sanely characterize the global market activities this last December as approaching normal. They were so clearly the opposite. Each and every market was under obvious duress, displaying tremendous disorder the likes of which were entirely too reminiscent of 2008 (or 2015, if you are Asian).

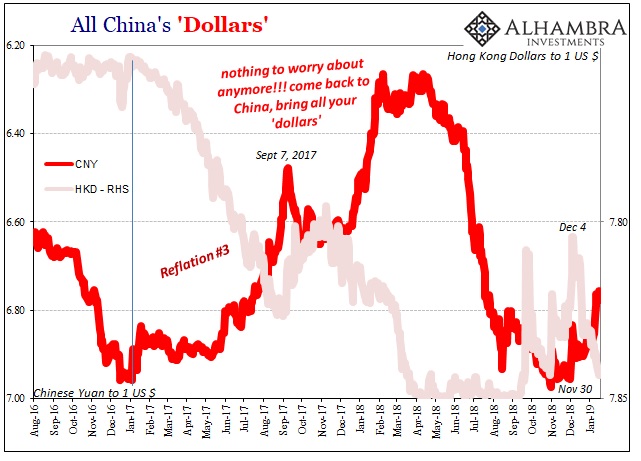

The one which stood out conspicuously as an island of stability curiously was CNY. Of all things. We all know the formula; CNY DOWN = BAD. It was very bad in December and CNY was…up?

Something else was going on. Part of it, I believe, was the moving focus, one taken off of EM’s more exclusively as it had been earlier last year. The eurodollar system was obviously alarmed over the currency crash, of which CNY was a prominent part. Those worries kept expanding and shifting, however, registering by October not just in China but also Europe and even the United States (everyone pretended it wasn’t happening, but WTI contango was the worst possible signal).

When EM’s are the sole issue, get out of China and go somewhere else (like US equities midyear). If it isn’t just EM’s, what do you sell out of and where do you go once you sell? UST’s and German bunds, obviously, but not much else.

One place nobody went was Hong Kong; so much for them as the safest monetary port in any global storm. If normalcy had meant, and would still mean, HKD was falling, then why was HKD falling throughout December (as early October) when chaos was almost evenly spread everywhere? The whole mainstream rationale behind HKD’s movements debunked yet again.

It isn’t nearly so obvious as it was during the last half of 2017, but the countermovement (in this case volatility) of HKD compared to CNY is nonetheless prominent. In other words, it sure does seem like the Chinese were up to using HK again in aiming to solve their “dollar shortage” in keeping with a currency stable priority. When it got really bad, when CNY was at most danger of being squeezed lower, HK was the one which got whacked.

With HKD rising in September, it provided some necessary margin for any banks which might provide any spare eurodollar capacities via Hong Kong. As it approached 7.85, HKMA’s limit, the dollars seem to have disappeared, HKD rebounds which puts the Chinese back into a bad position.

Rinse. Repeat.

It goes along with one reason why I believe CNY fell so hard after April 18 (notice how it corresponds to HKD hitting the lower boundary just one week prior). In January 2019, it therefore proposes the same sort of limit (as does any prospective “ticking clock” of the purely PBOC variety). Even as some things have come back since January 3, HKD has not.

It approaches 7.85 once more.

In the bigger picture, the Chinese agenda is further exposed. Reflation #3 was just that hollow, the PBOC almost certainly encouraging this back and forth between Hong Kong and Shanghai to be overdone. I’m almost positive it was on purpose, not a clumsy bureaucratic approach but an intentional display of power and conviction.

To put some weight behind Reflation #3, they used HK as a conduit which propelled CNY to miraculously retrace almost the whole of its prior 2014-16 plunge. What better way to assure the eurodollar world that things were back to normal? No more risk in China, globally synchronized growth was real. Bring all your dollars back, the dangers are all cleared out; can’t you see how fast and how far CNY jumped?

But therein lay the danger. What if nobody (or not enough) took the bait? For as high as CNY went, no dollars showed up on the PBOC’s balance sheet. Obviously, something was missing in what amounted to a shell game.

It can all unravel very quickly absent broad participation in the illusion, which then creates all sorts of new problems while accelerating the rate at which those new problems spread elsewhere. If you are looking for a brief description of 2018, that’s probably the best one.

As I wrote back in the middle of 2017:

Since then, HKD as well as Hong Kong money rates (HIBOR) have started to share open and clear linkages to Chinese money rates and currency changes. What that means and what those might be isn’t clear, except as to propose a couple of interpretations. China and Hong Kong may not monetarily be as separated as thought even as late as January 2016; as much as it can seem at times, maybe the “rising dollar” isn’t completely dead just yet.

If it isn’t, like a smoldering ember biding its time beneath the ash of prior conflagration, it could mean more than a mere currency oddity. Hong Kong is supposed to be a boring place for money and currency, but it is increasingly interesting.

In January 2019, HK is certainly back to being that again. There is no “good” interesting in this context.

Stay In Touch