Scarcely a week will go by without some grand prediction of the dollar being dethroned. Set aside how if anything is to be deposed it would have to be the eurodollar, these stories typically follow the same formulaic approach: Country X is moving away from dollar reserves, “diversifying” its holdings because of the geopolitics of Y.

Usually, it is the Chinese who are set to play the role of upstart. It makes sense. As the world’s second largest national economy coupled with far greater international aspirations, why not yuan?

This from just a few days ago:

China is heavily exposed to the U.S. dollar, but now, with the risk of “decoupling,” Beijing is silently diversifying its reserves to reduce its dependence on the world’s largest reserve currency, analysts say.

Or how about this one:

Fresh data suggest China is moderating its appetite for investing in U.S. securities, a trend that could mean lower flows of cheap capital from Beijing and a possible rise in borrowing costs across the American economy.

An analysis of U.S. Treasury data suggests China, with $3.2 trillion in foreign-exchange reserves, has begun to rapidly diversify its currencies portfolio.

This other quote, though, that was from March…2012. China, as you might recall, has been “diversifying” its reserves for going on a decade now. And the dollar yet dethroned.

According to the latest BIS numbers (triennial survey), the dollar denomination is still used as one side in 88% of all the world’s forex transactions. RMB: 4%.

Why?

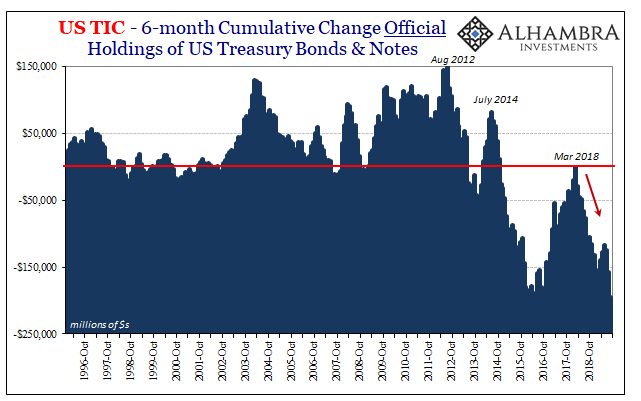

To begin with, there’s a fundamental misunderstanding about the idea of “diversifying.” Actively switching out of US$ assets is one thing, and that’s how it is written up (oh, I meant to do that!), but what most often happens is the “dollars” stop flowing to whatever foreign location and therefore the proportion of them in that location’s holdings necessarily falls. Especially when that very same place gets hit with a more extreme case of having to outright sell US$ assets – as so many have done especially since 2014.

They’re not intentionally diversifying so much as being stripped. Big difference.

It all gets back to a greater confusion about the reserve currency itself, not just in how these are eurodollars but more so the functions of them.

What is a reserve currency?

Most people don’t really know how to answer that question, including and especially the “experts.” I described its requirements a few months back:

A reserve currency is an intermediator, more than a buffer between national systems often with very little in common…If [both] sides can use a currency that is common in both areas it then obviates the need for either of their national denominations…The downside is that this requires a whole lot of that middle currency to be made available practically everywhere.

Making a whole lot of that middle currency available takes a whole lot more than you might think, certainly well beyond mere government intentions.

It is Triffin’s paradox, only that “paradox” has been solved in an unexpected and grossly unappreciated way. What Robert Triffin said long ago was that no national currency would be able to perform essentially two roles: creating enough for the demands of a globalizing world while at the same time maintaining the confidence in it while so much of it was being “printed” from nothing.

The eurodollar system in one important sense was an elegant solution to Triffin’s dilemma; being in the shadows, and being misunderstood, left off almost every monetary statistic, there could be “enough” “dollars” for a world that needed more and more and more of this intermediating middle currency. And it would create them on-demand in ways that easily satisfied those needs.

The Japanese understood what it took, which is why in the seventies and eighties they attempted to create a Samurai bond market – the securities market to evolve alongside euroyen – to challenge the eurodollar/Eurobond regime. It failed because, even before 1989, it never achieved enough depth, fluidity, and reliability (the deep infrastructure of banks and other financial firms operating there) to fulfill the role of a true reserve currency.

Company A in Europe couldn’t easily, dependably, and efficiently raise euroyen via bond or bank offerings so that Company B in some emerging market would accept payment in them. That’s the other part of “infrastructure”; once Company B has that middle currency, can they easily use it for something?

In eurodollars, the answer is always yes. In RMB, as euroyen, a resounding no. There is no depth to the offshore yuan market, even when Chinese authorities were pushing for one (CNH in Hong Kong). There was no substantial degree of breadth across that arena which might’ve incubated a place where companies round the world could use yuan for both sides of the global reserve.

To put it simply, and bluntly, there’s nowhere near enough RMB. There’s not even enough RMB for inside China.

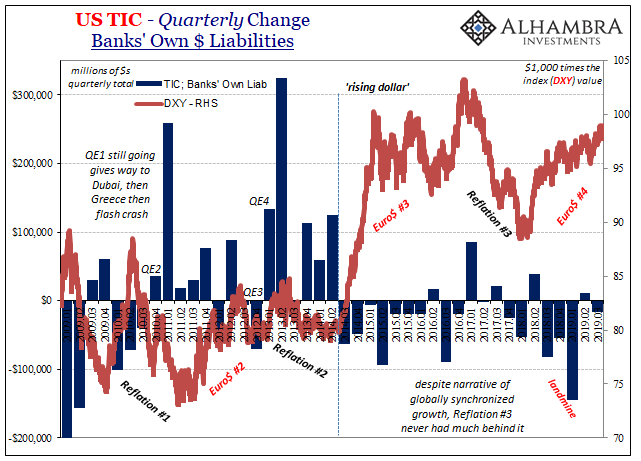

And since 2014, offshore yuan has only dwindled. As a result, where it actually matters, the banking system, the dollar not only rules it rules completely unchallenged. What do I mean by that? Footnote dollars, the real depth behind this reserve system and it is damn near monolithic still some ten years after the Chinese first started (rightly) complaining.

This is infrastructure (from the BIS in 2017) you will not soon see from any other currency denomination, especially yuan:

The dollar reigns supreme in FX swaps and forwards. Its share is no less than 90%, and 96% among dealers. Both exceed its share in denominating global trade (about half) or in holdings of official FX reserves (two thirds). In fact, the dollar is the main currency in swaps/forwards against every currency.

That is a true middle currency, the intermediator between almost everything globally – not just for trade purposes but far more often than not financial “flows”, too. This is no trivial distinction, as I write elsewhere:

You want to swap yen for UST’s? Credit-based “dollars.” You want to swap yen for Singapore bonds? Credit-based “dollars.” A company in Brazil wants to ship China raw material? Credit-based “dollars.” A firm in Europe is trying to build capacity in Thailand? Credit-based “dollars.”

Unless and until the banking system moves away from dollars, diversifying national reserve holdings means absolutely nothing. Nothing. In fact, more than anything, diversifying signals that there are still big problems in the eurodollar system.

In other words, even as it struggles and creates thorny issues for the whole world economy and financial system, it continues to dominate no matter how many dissatisfied customers. It tells you how a great deal about how difficult and how substantial it must really be to create and maintain this reserve system; that despite a decade’s worth of noise, fury, and quite often heartache, there is simply no realistic alternative.

At the very least, it keeps the lights on. Barely, at times.

We are stuck with this arrangement largely because the media, politicians, central bankers, etc., don’t know a thing about it.

We all need a different middle currency, and many places recognize that need even if they haven’t quite figured out why. But we will continue to be nowhere close to getting one until the “why” becomes more than constant stories about national “diversification” of reserves and the unsubstantiated shrieking of a dollar on its way to being dethroned.

Those, the diversification and the shrieking, are mere symptoms of a much, much bigger story.

Stay In Touch