It’s actually one of the few areas that has been studied in mainstream Economics. The links between global financial upset and broader economic consequences are pretty well understood. Trade gets shut down, therefore economies which are highly dependent upon the exchange of goods experience the effects first. When you see these bellwethers under pressure, it’s a bad sign.

The mysterious part is where these financial problems might come from. It’s one of the more uncomfortable aspects of the 2019, being in agreement with Economists who can clearly see that “trade wars” just aren’t significant enough to be this much of a disruption. In addition, it’s a huge stretch to believe that worries over a few billion in future US tariffs on Chinese goods would’ve produced such a decline in trade conditions starting all the way back to the middle if not earliest days of 2018.

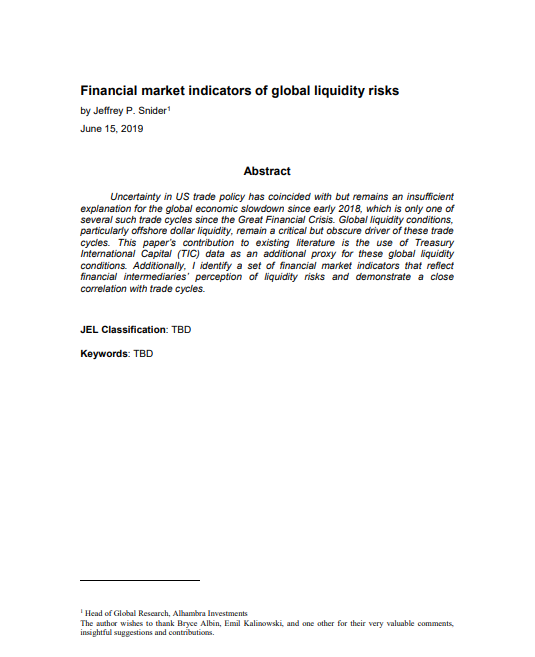

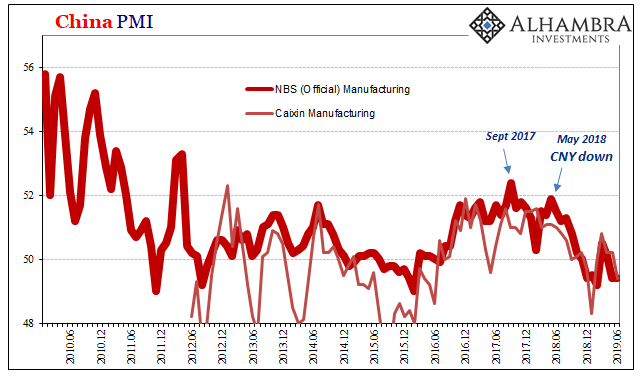

The latest flood of PMI’s particularly dealing with manufacturing make both points. This slowdown becoming a full-blown downturn isn’t a new development, and it’s getting serious to the point that US-China geopolitics are set aside as immaterial.

In South Korea, IHS Markit’s Manufacturing index dropped to 47.5 in June 2019 from 48.4 in May.

The continued weakness exhibited by the South Korea Manufacturing PMI during June primarily reflects the ongoing global trade slowdown. Panellists [sic] reported that this is taking its toll on their businesses, weighing on demand for goods and subsequently leading to cuts in production.

The Japanese are starting to see employment weakness develop as a second order effect.

Subdued export demand resulted in the sharpest drop in new work from abroad since January. An associated decline in pressure on business capacity led to more cautious staff hiring in June, with employment growth easing to its weakest for just over two-and-a-half years.

This doesn’t mean that China isn’t included. The problem, in fact, seems to be the Chinese economy. No one can account for what’s going on there because there is no official or mainstream explanation other than trade wars. Tariffs are the only thing anyone talks about; therefore, it must be them.

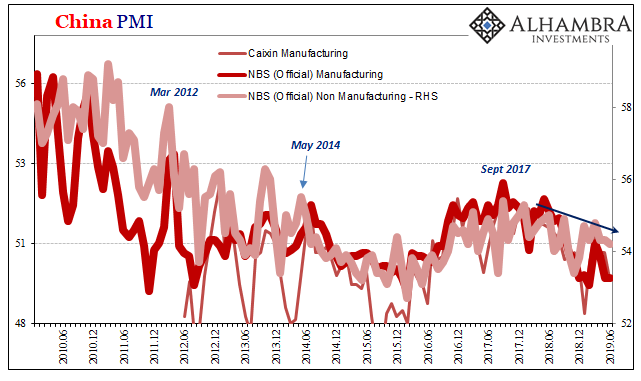

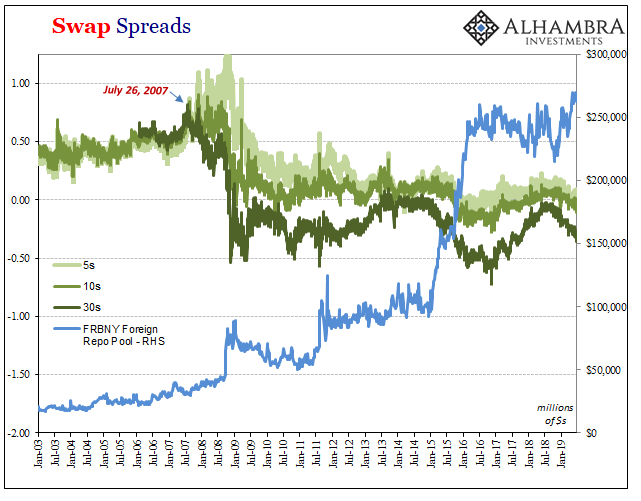

Understanding instead the monetary mechanisms behind all this, we can see how the current disruption in global trade isn’t really different than the prior bouts of weakness. It is the repeating succession of monetary issues.

Both versions of China’s manufacturing sector PMI’s came in at 49.4 in June. The official index maintained by the government’s National Bureau of Statistics includes all the state-owned behemoths which at times can reflect more of what the government is doing than the rest of the economy. The other survey, the Caixin PMI, attempts to isolate conditions in the private economy by including mostly smaller and medium sized businesses.

That the two now equal suggests a couple of important points. The first is “stimulus”, or the distinct lack of it. The Communist government, as we’ve pointed out for a while, just isn’t coming to the rescue despite all the Western disbelief. Instead, what seems to be the official if undeclared doctrine of “managed decline” remains in place.

The second point is the second part: decline. China’s vast manufacturing sector appears to be doing just that. And it is China’s economy, not the trade stuff, which is where weakness originates. From Caixin:

Overall, China’s economy came under further pressure in June. Domestic demand shrank notably, foreign demand was still underpinned by front-loading exports, and business confidence fell sharply. [emphasis added]

According to these figures, Chinese industry is being supported right now by “trade wars” as firms seek to stuff global supply channels ahead of anticipated tariffs (obviously at the expense of future production).

The rest of China’s economy is slowly being squeezed another external problem – the same one that so negatively impacts global trade unrelated to protectionism. Chinese monetary growth has ground to a halt as a result of the latest eurodollar squeeze, a global dollar shortage which not only acts as an external drag it also becomes the operating baseline for RMB.

The October-December landmine.

This is why, I believe, on a day like today the stock market can surge to record highs while investors cheer the prospects for a trade deal while at the very same time the bond market remains unimpressed either way.

The issue is entirely liquidity risk, meaning dollar shortage. The bond market sees this in global monetary conditions and hedges against it in a manner consistent with forecasting imminent FOMC rate cuts. This global PMI data therefore confirms the economic consequences of something that must already be substantial.

That isn’t trade wars.

Stay In Touch