I really like Joe Calhoun’s theoretical framework in explaining what we try to do here. Like a game of Poker, we are playing against everyone else at the table unlike Black Jack where you are largely playing yourself. It helps explain why I can say the FOMC is irrelevant while at the same time I spend so much time (all the time) dissecting almost everything it does.

People believe, and really want to believe, the central bank is a model of technocratic success; so much so some argue it should be replicated in other areas of government and life. Perish the thought.

Since people pay attention to the institution and what it does or doesn’t do, we are forced to play against it until the ugly truth finally emerges. This includes writing a second piece back-to-back on the same FOMC meeting minutes.

One of those truths is within the domain of its very core. The central bank is supposed to be first and foremost a bank. Money and all that. It wasn’t ever taught in Economics classes how a couple generations ago these central bankers just skipped out on it. After the “missing money” seventies Economists stopped looking for any.

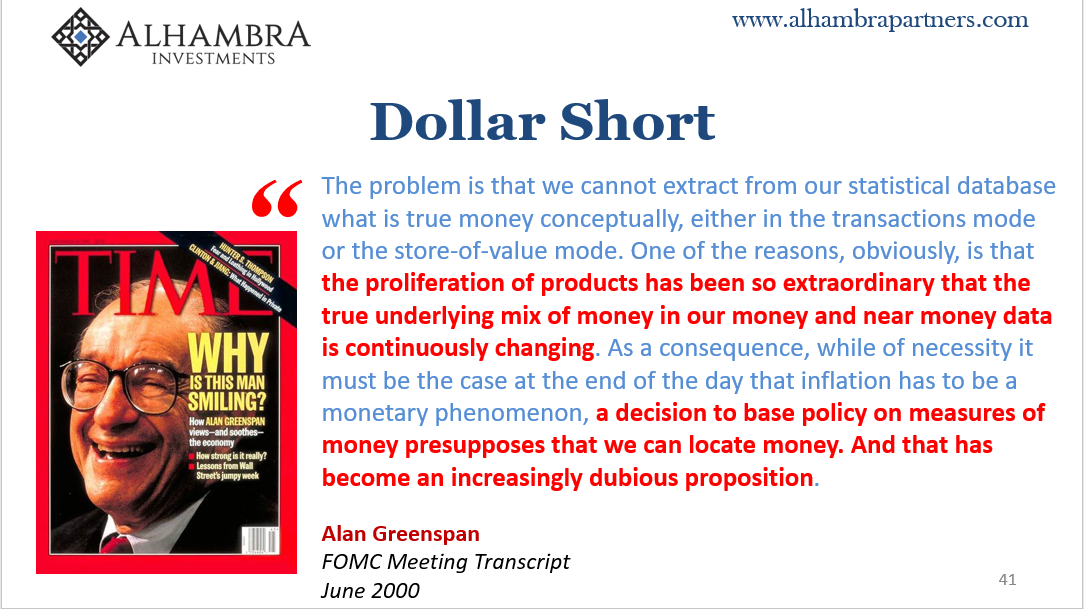

They realized it couldn’t be found and so began crafting another narrative – no one need define nor measure money because the single interest rate target will be a sufficient workaround. More than sufficient, it was thought to be an improvement; federal funds in the United States.

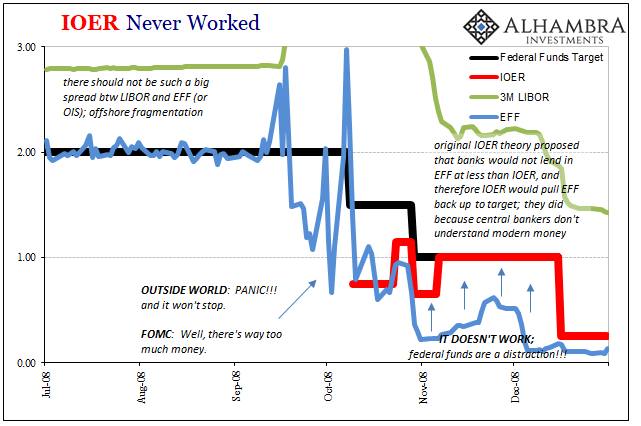

Perhaps because the world was fixated elsewhere, a lesser known, hugely unappreciated piece of the 2008 global panic was the gross misbehavior of this presumed core competency. It didn’t get any coverage, but this was a symptom of the primary monetary problem not just of the panic but everything that has followed. Moneyless monetary policy performed just as you would have expected during the first worldwide monetary panic in four generations.

Briefly, federal funds starkly disobeyed Federal Reserve targets, policies, and emergency measures (more than just the joke, IOER). Don’t fight the Fed? Domestic money markets spit in Bernanke’s face while offshore dollars disappeared and the financialized global economy with them.

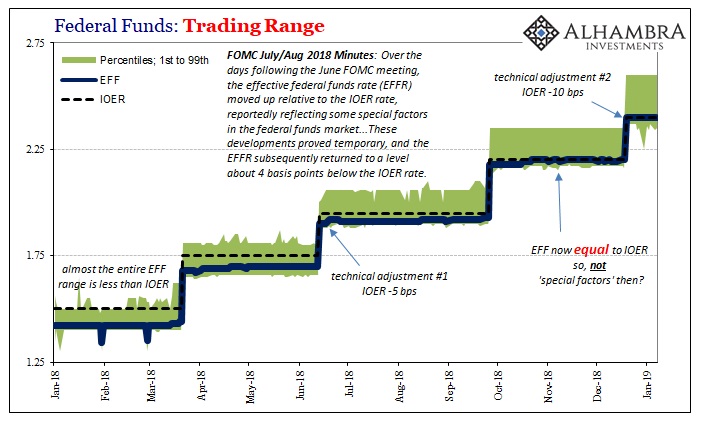

At the zero lower bound, federal funds faded into the background again superseded by repo, FX, and others. The issue of federal funds mischief was revived in 2018, however. So much so, the central bank performed not one but two “technical adjustments” aimed at it. To date, no one has bothered to ask Jay Powell if those might be in any way related to the spreading “anomalies” leading up to and including December’s alarming market “volatility.”

As I’ve written consistently, federal funds do not matter. There’s nobody there. The only reason the Federal Reserve continues to rely on the rate is that monetary policy is moneyless. The modern central bank regime is one exclusively of expectations, therefore the means for conveying those policy expectations becomes all-important.

In rather detailed and comically meaningless “exit” discussions taking place years ago, the FOMC decided to keep its federal funds emphasis anyway because it worried investors (and the public) wouldn’t be able to grasp the central bank transitioning to some other more relevant framework. Federal funds are tradition, nothing else, which was enough for the central bank and thus once more illustrating this larger point.

If there is obviously something wrong inside an empty market we can easily infer that there is probably some big problem out there in the real money world. If it registers in the farthest reaches of irrelevance like EFF, then it’s likely not some small issue.

Therefore, two technical adjustments and counting.

The FOMC meeting minutes for the December policy gathering provide a little more color on those. There was first a staff admission that EFF just might cross above IOER in the days, weeks, or months ahead. The timing of all this suggests perhaps sooner rather than later. Again, I say IOER is (an established) joke and according to the publication officials might suddenly be worried that’s the correct characterization of it.

The staff reviewed a number of steps that the Federal Reserve could take to ensure effective monetary policy implementation were upward pressures on the federal funds rate and other money market rates to emerge. These steps included lowering the IOER rate further within the target range, using the discount window to support the efficient distribution of reserves, and slowing or smoothing the pace of reserve decline through open market operations or through slowing portfolio redemptions.

Well, those “upward pressures” have emerged all over the place. The very fact that this rather lengthy discussion (actually it appears across two different sections of the minutes) is included at all shows that officials are keen on letting the public know they know there’s a problem. If policymakers were at all confident in IOER, they’d leave it out entirely.

But just like QE, if you have to do it more than once it didn’t work.

So, if federal funds are important only for signaling, what is signaled by federal funds that don’t behave? How can you not control the one thing you’ve always claimed you’ve controlled? These are rhetorical questions, obviously. If the Fed can’t get the most basic little things right, what confidence in anything else? December markets are your answer.

The minutes display some real concern on the part of the FOMC about this very thing. I guess the bond market hasn’t been “mispriced” all this time.

IOER doesn’t work, bring on the Discount Window. I’m actually laughing while I type this because the Discount Window hadn’t fared any better. In being so confident about expectations policy, central banks (not just the Fed) allowed their monetary competencies to wither and die really believing there was no downside to doing this.

Now that they somewhat realize these may actually be important, look at them scramble to try and revive some! These weren’t hawks suddenly transformed into doves, they’ve been chickens frantically running around without heads the whole time.

These are futile gestures, ultimately. There is just no way central bankers are going to catch up on the decades of monetary evolution that took place since money went missing. It is, however, becoming more obvious this large gap between what needs to be done and what central bankers can actually do. That’s the only and smallest sliver of a silver lining, especially in light of the renewed prospects for another global economic downturn.

Stay In Touch