Most of the best circuses used to have three main rings. Nowadays, we can only get the occasional show for two on the same day. It is a rare treat when central bankers from two major jurisdictions compete for the world’s misapprehending attention. Today is one of those days: Mario Draghi and the ECB as the warmup act for the Federal Reserve’s release of its last minutes.

Draghi is in rare territory, coming very close to pulling a Trichet. Jean-Clause was, after all, Mario’s predecessor unceremoniously asked to “retire” in late 2011. Why late 2011? Every reason.

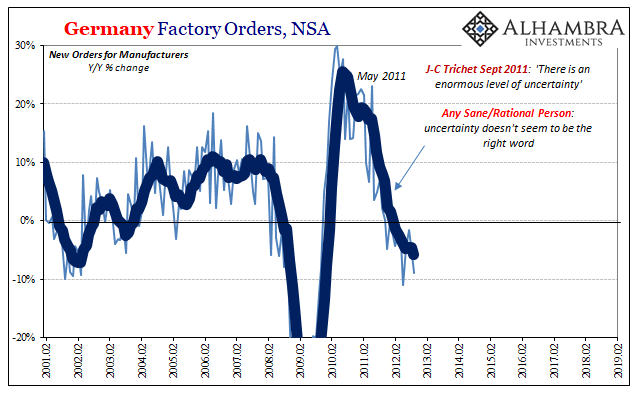

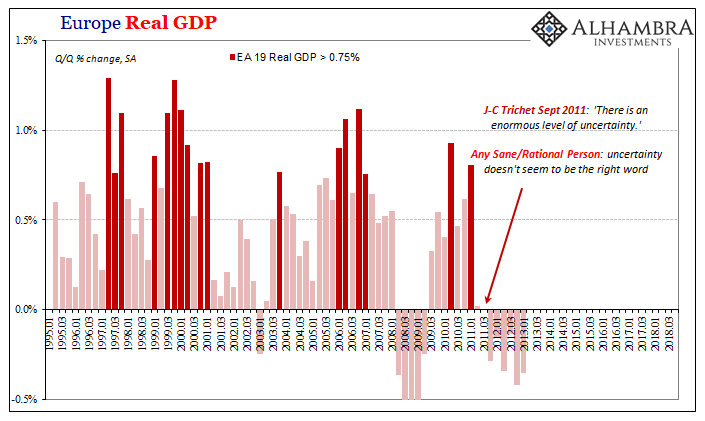

Specifically, though, Trichet saw a huge, powerful recovery that year. Predicated upon his own brand of monetary genius, the European economy was going to really boom (where have we heard this before?). By 2012, he thought, it would be too late to act. Rate hikes were demanded to slow down the growth before it spiraled out of his hands.

Obviously, that’s not what happened; not even close. The rate hikes, did, for sure. Jean-Claude wasn’t bluffing. Rather than boom, Europe stalled into recession (for reasons having nothing to do with two 25 bps increases in short rates). Meanwhile, Trichet and most every other Economist plumbed the depths of denial while it happened.

Even as late as September 2011, just as the ECB’s econometric models started to get wobbly and 2012 growth expectations began their track of (typical) downgrades, the most the ECB’s President would say was, “There is an enormous level of uncertainty.”

That paled in comparison to the first time, though. People forget but the ECB did the same thing in 2008. Europe’s central bank was raising its benchmark corridor rates, then, too, only in 2008 the European economy was already gripped by devastating recession while they did. The only reason Trichet managed to make it to 2011 was his stupidity hardly stood out that year.

In February 2008, Trichet had concluded only that, “Uncertainties about the prospects of economic activity are unusually high.” Not high enough, apparently, for his optimistic standards. He had bet on Europe and the rest of the world decoupling from what everyone believed (and many still do) was a US subprime mortgage debacle.

As I recalled a few years ago, the ECB was fooled, twice, by nothing more than crude oil:

In the summer of 2008, oil had surged even though the financial state of the world was fatally compromised. In fact, the very reason for the jump in oil prices might have been, as I would argue, because of that funding condition. In a world where internal financing runs on collateral and where the dominant form of collateral [MBS] was actively being repudiated, anything else will do no matter how seemingly ill-suited. There was no shortage of cash especially in certain places, as witnessed by the tendency of the effective federal funds rate to run shallow to the target at times of increasing stress, so it was only a matter of process by which those with cash would find something collateralized to do with it.

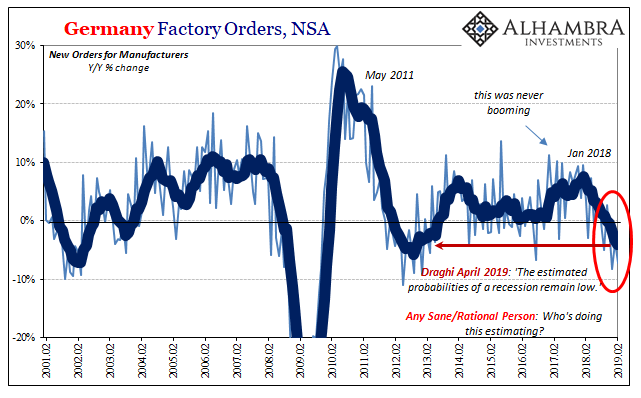

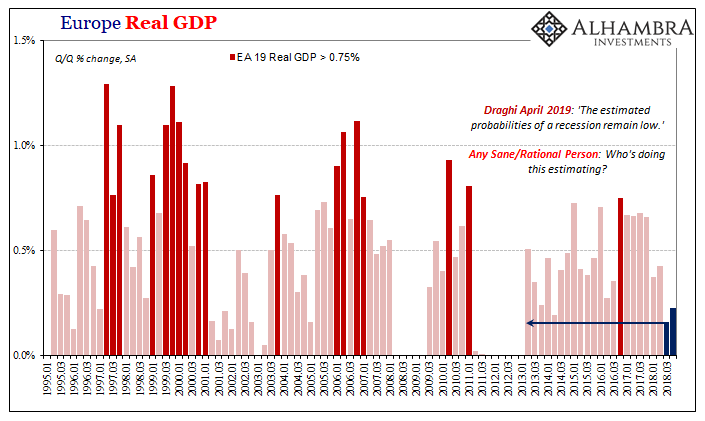

Benchmark Brent crude seems to have made it a perfect trifecta with 2017’s reappearance.

Mario Draghi today said practically the same thing as Trichet did on those two prior occasions. First, the current ECB chief acknowledged, “Incoming data continue to be weak, especially for the manufacturing sector … The slower growth momentum is expected to extend into the current year,” before pivoting to “The estimated probabilities of a recession remain low.”

It sounds like a whole lot of uncertainty.

The FOMC minutes show that many on the US central bank’s main policymaking committee agree. “A few participants noted that there remained a high level of uncertainty associated with international developments…”

It’s not just the economic forecasts where this ambiguity resides. Back to the FOMC minutes:

Several participants expressed concerns that the public had, at times, misinterpreted the medians of participants’ assessments of the appropriate level for the federal funds rate presented in the SEP as representing the consensus view of the Committee or as suggesting that policy was on a preset course. Such misinterpretations could complicate the Committee’s communications regarding its view of appropriate monetary policy, particularly in circumstances when the future course of policy is unusually uncertain.

This is what the kids call gaslighting, and it’s a common technique especially in these sorts of political circumstances. There was no uncertainty about anything just several months ago at least insofar as official interpretations were concerned. When oil prices were up meaning inflation indices, too, there was absolutely no doubt in the official collective mind about what that meant.

Noted earlier today in the specific context of inflation, here’s Jay Powell again during his first month in office. Doesn’t sound the least bit conflicted, does it?

Now since then — we will submit another projection, all of us, in three weeks — but since then, what we’ve seen is incoming data that suggests that strengthening in the economy. We’ve seen continuing strength in the labor market. We’ve seen some data that will, in my case, add some confidence to my view that inflation is moving up to target. We’ve also seen continued strength around the globe, and we’ve seen fiscal policy become more stimulative.

Complaining in March 2019 that people (mostly in the media, certainly not in the bond market where it would actually matter) were taking the dots so seriously is unmistakably too Shakespearian; the Committee doth protest too much, methinks.

When oil is up the dots are serious science never to be challenged (remember the mispriced long end of the bond market?); when it all goes to hell, unexpectedly, wow, the uncertainty.

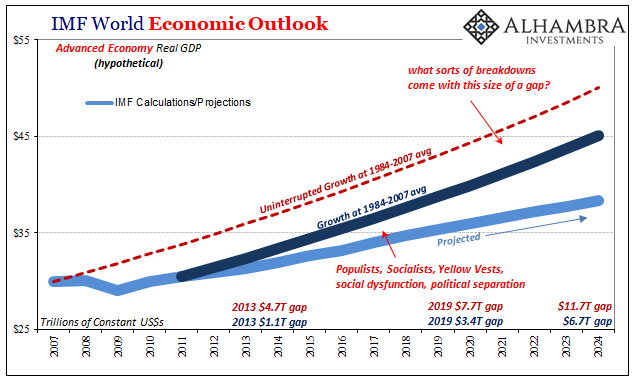

It’s nothing new, which is entirely my point. This has been ongoing since 2008, now the fourth eruption of global uncertainty. There is never anything more than temporary reflation, never recovery. There are only false dawns, which 2019’s official uncertainty officially confirms today in two places at once. The circus is back and in full swing.

They really don’t know what they are doing. Not a single one of them anywhere. We are right back in the same worst case because we never really left it.

Stay In Touch