Trade wars are rapidly turning into subprime mortgages. A few billion in tariffs will have wrecked the entire global economy, they’ll claim. Just like all that toxic waste subprime mortgage fiasco led inevitably to the Great “Recession” and global panic. Neither will be true, except insofar as both were symptoms of the far greater cause. The other thing actually responsible for messes.

Both of them.

For one of the few times, I have to agree with what Ben Bernanke said when he told the Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission (FICC) an inconvenient fact about specifically high risk housing loans.

Prospective subprime losses were clearly not large enough on their own to account for the magnitude of the crisis.

Though the Commission heard this testimony, that’s not quite the conclusion they reached. Either of them. There were actually two final reports: one written and published by the majority Democrats, the other written and published by the minority Republicans. The Panic of 2008 all-too-predictably became tainted with partisan politics at the expense of the truth.

As I observed last year on the tenth anniversary of Lehman Brothers:

Among the more than 1,100 pages that in both versions make up the official account of the Great Financial Crisis of 2008, there are together zero instances of the words “offshore” and “eurodollar.” Pace Bernanke, how then could something like subprime turn into a massive global disruption? Without eurodollar and offshore, you have no idea.

And that’s why “we” are going to be blaming trade wars. It’s 2019, all the warning signs have gathered and have been sharpened. There’s an economic storm brewing, maybe a big one. The markets are all saying, get ready.

There was some initial hope after last year’s disruption this would all blow over. Transitory factors, many claimed. From Europe to DC, central bankers will always tell you “subprime is contained.” They won’t tell you how even if that was true, it still wouldn’t matter because subprime wasn’t really the problem. Most of them really don’t know any better.

Much of the distress and uncertainty surrounds China. This is quite convenient, or inconvenient in my case. China just so happens to be the epicenter of these trade wars. And the same country remains the major focus of the offshore eurodollar system’s revived decay impulse. The first will help hide the second.

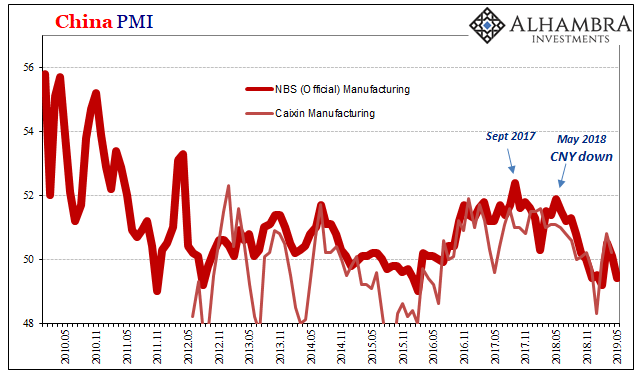

On April 1, China’s National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) reported a pretty substantial rebound in its manufacturing Purchasing Managers Index (PMI). Having sunk below 50 for three straight months up to and including February 2019, a low of 49.2 in that month, the index managed a 1.3 point rebound in March alone. At 50.5, disregarding the noise of the series, it looked to many like green shoots, good evidence for transitory factors.

Those hopes have been predictably dashed. Last month, the NBS calculated its manufacturing PMI fell to 50.1. Today, the Chinese government says in May it was 49.4; just 0.2 above the low in February.

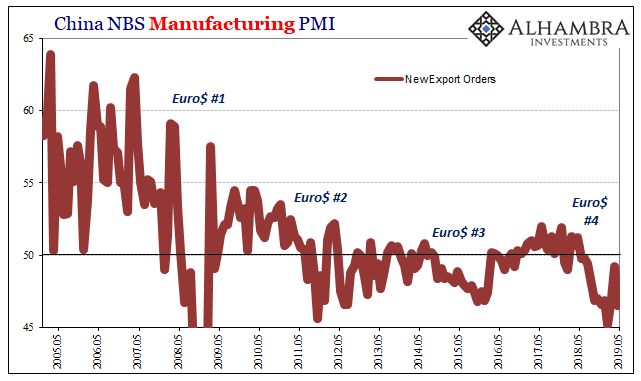

Leading the decline was the component for, you guessed it, New Export Orders. These had staged a much milder comeback than the headline, rising only to 49.2 in April. The current estimate is an atrocious 46.5, a decline of nearly three points in just this latest month.

While that looks like tariffs and indeed those have almost surely contributed to the very clear contraction in China’s global trade conditions, the PMI as well as other similar accounts from around the world, not just China, tell a different story. In this one index alone, orders have been under 50 in every month going back to last May (CNY DOWN = BAD; May 29).

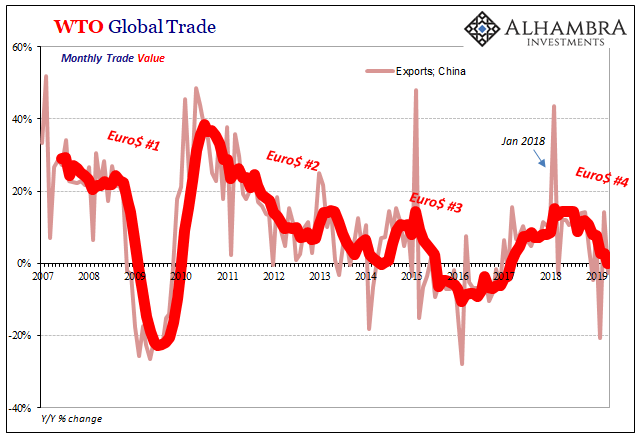

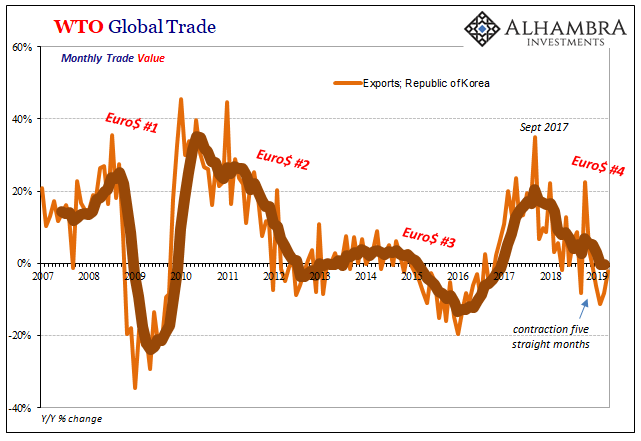

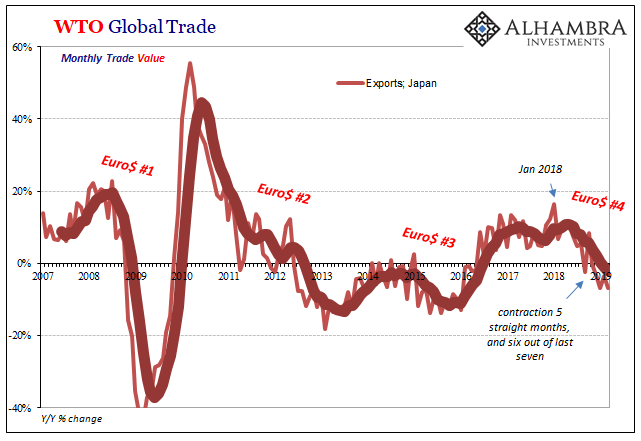

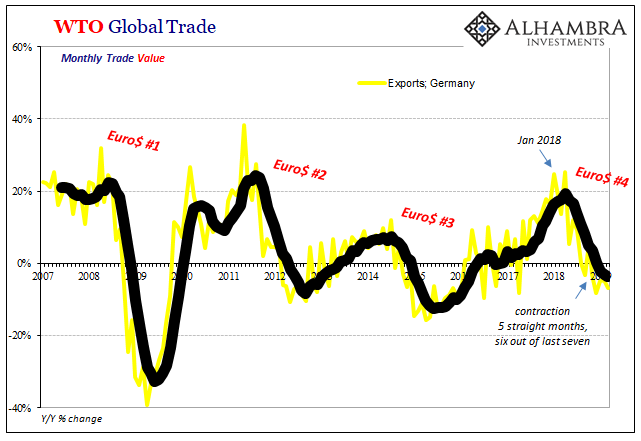

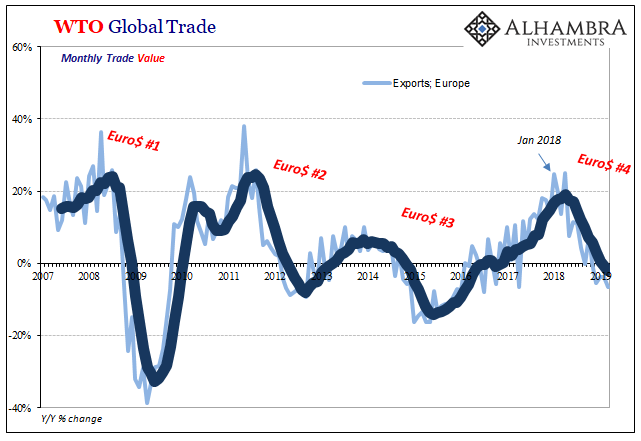

Separate statistics from the WTO on the subject of global trade display remarkable consistency. What was termed globally synchronized growth even into the middle of last year had already shifted to globally synchronized downturn. Consistent with this Chinese data, a sentiment indicator, and a government one at that, the WTO export figures align with market not political events.

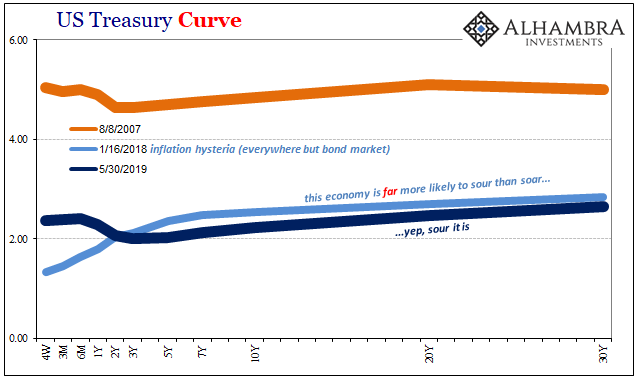

And so on. Each points toward January 2018 as the high water mark for the last expansion, such that it was. At the end of January 2018, while inflation hysteria was in full throat, global markets were rocked by a liquidation event which for several weeks even managed to capture stock markets. Global trade is first susceptible to the squeeze of tight global money.

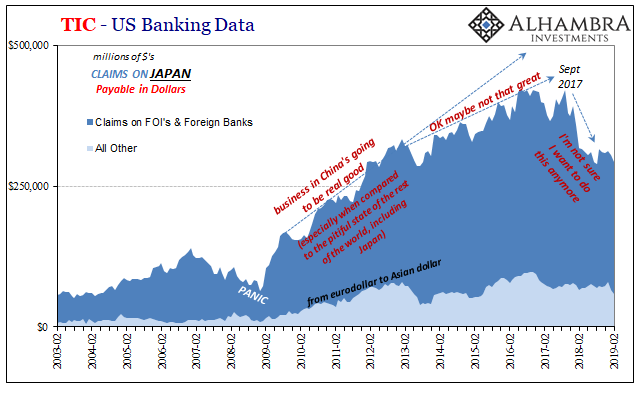

The dollar stopped falling at that point. It would soon turn around just in time for April’s EM fireworks and then May 29 last year. There weren’t imposed trade restrictions at that time, but there were very unnerved Japanese banks who have been right at the center of global dollar redistribution in that offshore eurodollar system.

Only, by January 2018 there weren’t. And it was the Chinese in October of 2017 who were responsible.

Ever since the global eurodollar panic ten and eleven years ago, Tokyo has become a vital center for global “dollar” redistribution. Some people call it the yen carry trade, but in doing so they leave out several important distinctions: first and foremost, Japanese banks don’t need to borrow in yen, they’re already stuffed with “bank reserves.” They only need, therefore, two additional factors: someone to swap into US$’s with, before then “re-investing” them elsewhere (redistribution), and the willingness to do so.

This doesn’t have to be an either/or situation. Tokyo’s dollar market participants might find FX funding a bit too expensive which then makes them less willing to engage in redistribution; which makes global dollars even more expensive, and so on.

So much of that dollar focus was aimed at China, the last of the growth prospects in the post-2008 world’s “new normal.” Except, after 2011 the new normal grabbed onto China’s economy, too, strangling likewise from within and without. It wasn’t until the outset of 2014 that this became the accepted view of most non-Japanese global money participants (CNY DOWN).

And it wasn’t until October 2017 that it was finally broadcast as the official view of the Chinese government. Apparently this was the last straw for Tokyo’s institutions. Western leaders, authorities, and the financial media were all too busy focused on the emotional tug of globally synchronized growth masquerading as analysis to notice.

Everyone is still too distracted; thus, it may seem to most that this is all some very new development, an unexpected setback that must be due to a few billion in tariffs. Like toxic waste a decade ago, it’s all anyone is talking about.

Trade wars are already very close to becoming 2019’s subprime mortgages. It doesn’t matter that just like the middle 2000’s bond market, Greenspan’s “conundrum”, the yield and eurodollar curves throughout all of 2017 were telling you this offshore eurodollar restraint was likely to happen. Again.

Stay In Touch