In the official narrative, the economy is robust and resilient. The fundamentals, particularly the labor market, are solid. It’s just that there has arisen an undercurrent or crosscurrent of some other stuff. Central bankers initially pointed the finger at trade wars and the negative “sentiment” it creates across the world but they’ve changed their view somewhat.

A few billion in tariffs, even if we include what is to this point only proposed, that’s just not enough to create these more serious distractions. That’s why Economists and central bankers keep referring to sentiment rather than speaking specifically about the restrictions themselves. Searching for a channel which would explain how something so small could be having far greater and more widespread effects, all they have is emotion.

There’s something else going on. It’s taking place overseas and it’s starting to really threaten the US system, too.

According to Federal Reserve Chairman Powell toward the end of June, these other global factors whatever they may be seemed to have been receding in May. Policymakers grew confident in their second half rebound scenario – the underlying fundamentals would reassert themselves once the mysterious “transitory” demons dissipated.

So far this year, the economy has performed reasonably well. Solid fundamentals are supporting continued growth and strong job creation, keeping the unemployment rate near historic lows…Along with this favorable picture, we have been mindful of some ongoing crosscurrents, including trade developments and concerns about global growth. When the FOMC met at the start of May, tentative evidence suggested these crosscurrents were moderating, and we saw no strong case for adjusting our policy rate.

Powell then probably stunned his audience when he admitted “the crosscurrents have reemerged.” Perhaps somewhat due to trade sentiment, he said, but by and large because “incoming data [is] raising renewed concerns about the strength of the global economy.” Overseas turmoil is being stubborn.

He may have said that the economy has performed reasonably well, but that’s also a purposefully imprecise characterization. Reasonably well doesn’t beget rate cuts. Those are the result of downside risks first which then become a realized downside.

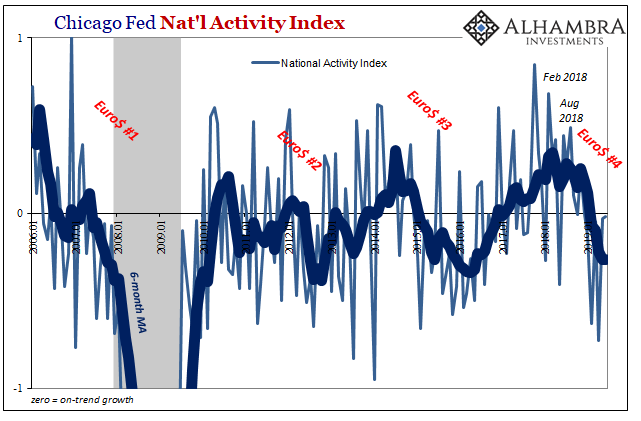

In terms of more recent data, we can start with the Chicago Fed’s long ago attempt at an inflation predicting algorithm. The branch’s National Activity Index hasn’t lived up to its inflation agenda, but it does suggest some general economic implications.

Composed of 85 separate indicators, the index is stitched together from them in order to come up with an average of zero and standard deviation of one. All that means is a positive reading indicates above-trend growth while a negative monthly figure tells us the economy is likely operating below trend.

Going back to last summer, Chicago’s NAI traversed the October-December landmine and came through it having transitioned from seeing slightly above-trend growth to now below-trend growth. Updated last week to June 2019, the index has remained in this shape halfway through 2019. Could be crosscurrents, could also be deeper concerns underlying fundamentals.

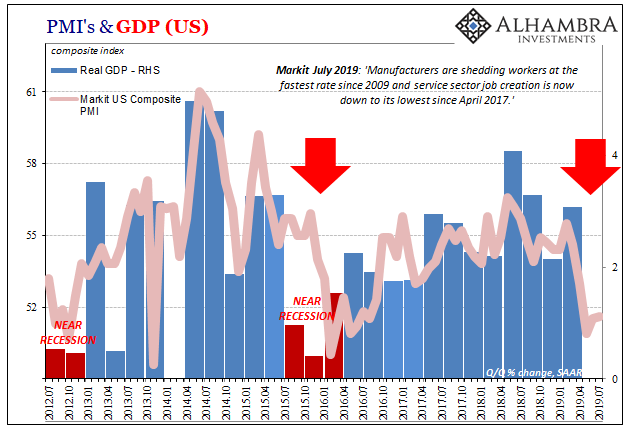

PMI data from IHS Markit, released today, builds upon the latter theme. The Composite Index, covering both manufacturing and services, hovers at just above the recent lows of 50.9. The latest value is just 51.6 – which is pretty consistent with current estimates for Q2 2019 GDP being between 1.5% and 2.0%. We’ll find out GDP on Friday.

Inside Markit’s numbers, there were a few parts that stand out with relation to fundamentals and the balance of risks to them.

Manufacturers are shedding workers at the fastest rate since 2009 and service sector job creation is now down to its lowest since April 2017. Future prospects have also darkened to the gloomiest since comparable data were first available in 2012, suggesting that companies may look to tighten their belts further in coming months, dampening spending, investment and jobs growth.

Markit’s Chief Business Economist Chris Williamson blamed, of course, trade sentiment and geopolitics before, like Powell, confessing that there’s other stuff going on; “increasingly widespread expectations of slower economic growth at home and internationally have all pulled business optimism lower.”

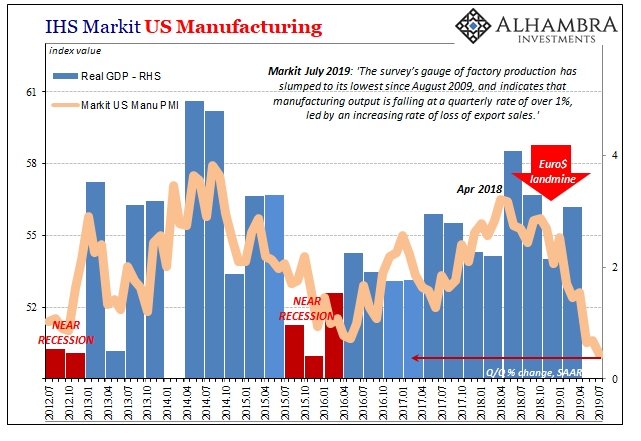

It is hitting the manufacturing segment first and hardest. That base portion of the composite PMI fell to exactly 50.0 in July – the lowest in the last 118 months going back to the autumn of 2009. Of that, manufacturing output dropped to 48.9, therefore suggesting why manufacturing workers might already be getting laid off.

At root on the manufacturing side is “an increasing rate of loss of export sales.” Again the theme of general global weakness (working its way through global trade first).

The combination of contracting output plus an increasingly very dour outlook among not just manufacturers but participants across the whole economy has the potential to fundamentally (further) alter the current condition.

If you are Jay Powell, crosscurrents or something else doesn’t really matter. You have to act if for no other reason than to change the sentiment – some rate cuts to brighten people’s outlook and give them some sense of hope and optimism that things will pick up before the self-reinforcing recessionary spiral sets in (if it hasn’t already at least in some parts of the economy).

This is why the Fed will cut “rates” next week just seven months after last raising them. According to the central bank’s econometric models, this will be insurance against further crosscurrents because of what it will do for economic sentiment; not what it will do in terms of banking and money where porous floors are unsurprisingly not working out well as filter ceilings.

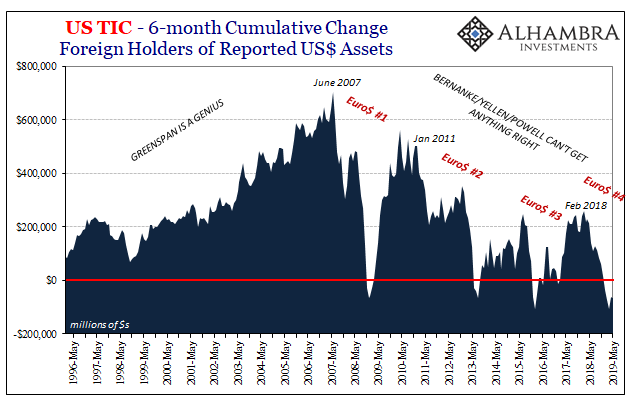

Out here in the real world, monetary policy theater doesn’t play out that way. When you see it as Euro$ #4 rather than trade wars or some nonspecific overseas turmoil, all rate cuts will do is signal to the rest of the economy that even the last holdouts, the most optimistic group of optimists, see the weakness, too, and now consider it a more serious threat.

Outside of the central bank bubble, it already is and has been for some time. The monetary irregularities of the past year and a half are coming home to roost in a broader cross-section of data. Euro$ #4 appears already to have nastier tendencies.

Stay In Touch