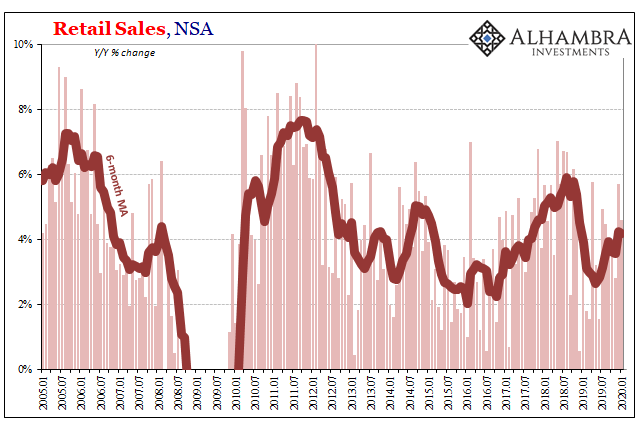

The lull in US consumer spending on goods has reached a fifth month. The annual comparisons aren’t good, yet they somewhat mask the more recent problems appearing in the figures. According to the Census Bureau, total retail sales in January rose 4.58% year-over-year (unadjusted). Not a good number, but better, seemingly, than early on in 2019 when the series was putting out 3s and 2s.

As has been the pattern in these things, global synchronized downturns, the middle part of last year sets up the annual numbers on the back end. Seasonally-adjusted, retail sales are on a losing streak that dates back to September – the very month when, we keep being told, everything started to get better (except the repo market).

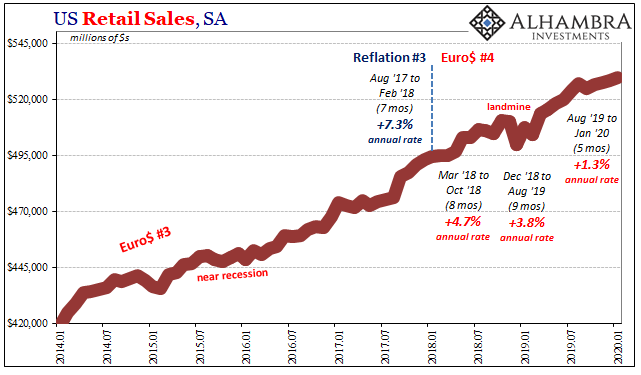

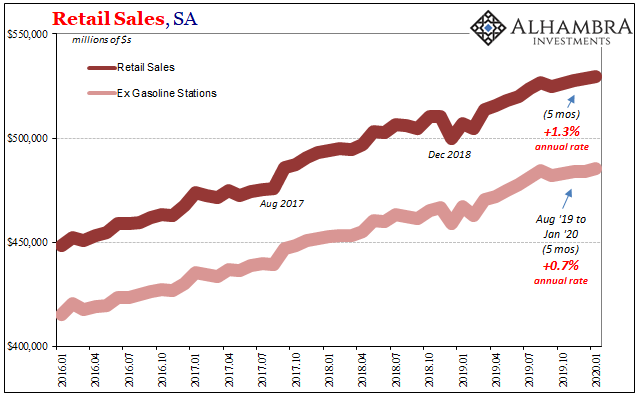

Beginning with September 2019 and dating through the latest monthly data for January, however, total US retail sales are rising at a recessionary 1.3% annual rate. Excluding the sales recorded by gasoline stations, the 5-month trend is nearer zero.

That’s more like what we see in the labor market from the perspective of JOLTS and CES hours than the revised and heavily smoothed rebound indicated by the Establishment Survey.

By itself, this doesn’t indicate recession but it does leave in place the tradition recession dynamics of the business cycle. These are: sales slow, inventory piles up, the supply chain cuts back leading to lower work, lower income and then even slower sales. All that started in the middle of 2018 (which the revised payroll data now agrees with).

To break the cycle only requires the very thing Jay Powell and his ilk have been predicting and practically guaranteeing. A strong labor market which re-asserts itself especially in the form of renewed consumer spending. This takes the pressure off the supply chain as inventory is moved out the right way (sales) rather than the wrong way (heavily discounted and more drastic cuts to new orders).

Five months into the promised rebound, the Census Bureau’s retail sales figures don’t register anything but a five month-long slump which now extends one month into the new year.

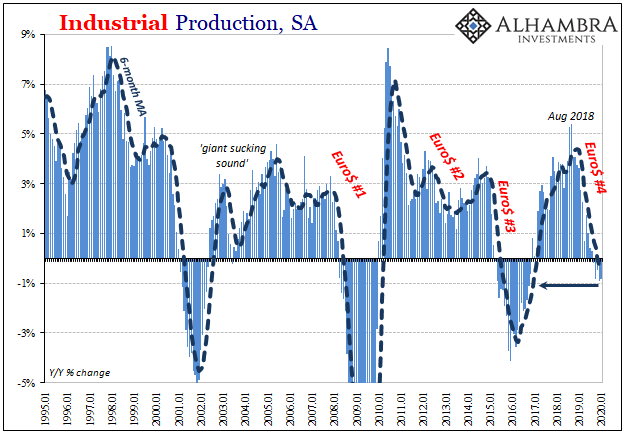

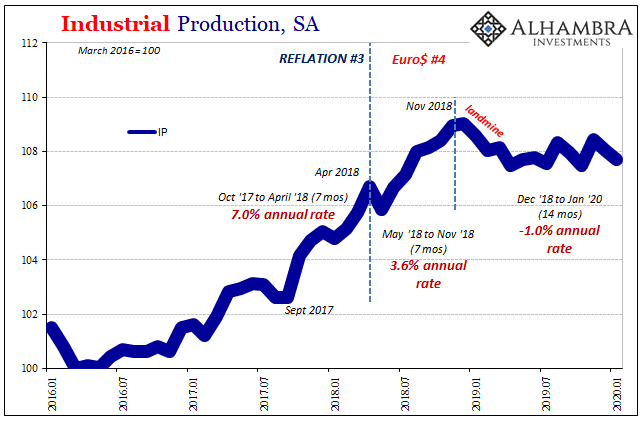

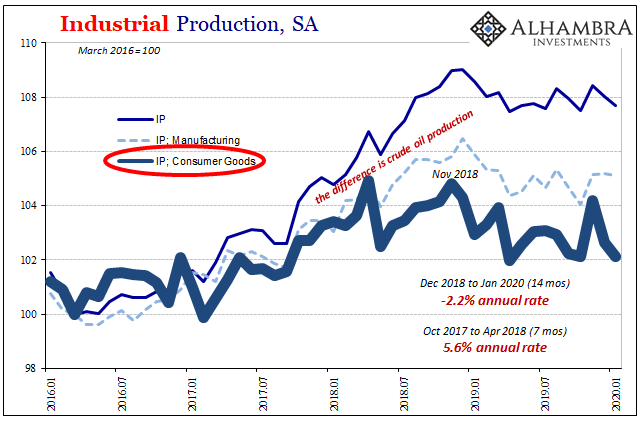

It isn’t much of a surprise, then, that the Federal Reserve also reports a continuing decline within US industry. Despite huge positive contributions from the renewed vigor in oil production, Industrial Production remains heading in the wrong direction.

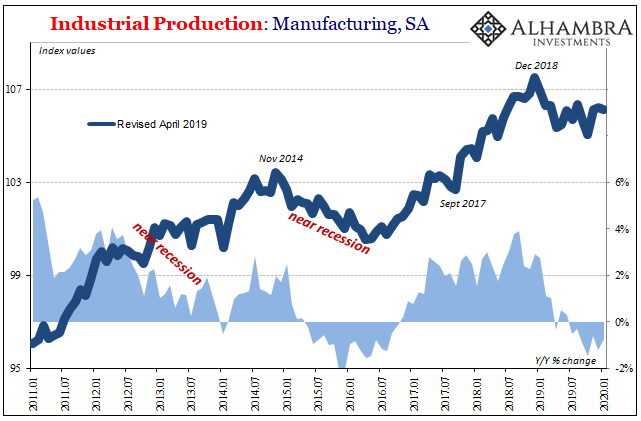

Dating back to the end of 2018 (the landmine), US IP is falling at a 1% annual rate. It doesn’t sound like a whole lot, but any decline of that magnitude in this statistic has been associated with recession or very close to recession in the past. An industrial setback is not something to be taken lightly and despite outward projections of confidence I doubt anyone at the Fed is actually that confident, this being one big reason why.

The fact that USIP wasn’t nearly as downright ugly as European IP is of little comfort, either. Europe is and has been a glimpse at our shared global future. These globally synchronized downturns aren’t perfectly synchronized; some systems get out ahead of others, taking the brunt of the squeeze before anyone else.

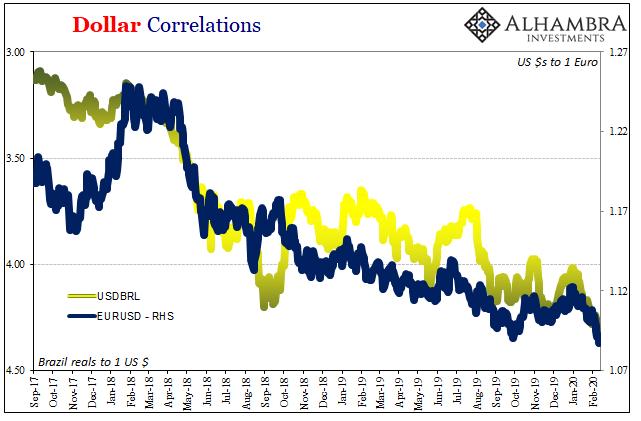

That’s been Europe and so far there is little indication anything has materially changed (especially where the almighty eurodollar is concerned).

With overall retail sales as they are and the BEA’s estimates for GDP showing a possible top in the inventory cycle, there is a very realistic chance manufacturing, in particular, is being set up for that possibility. The European scenario is not at all out of the question here (given the import and trade numbers) moving forward.

If the global headwinds and disinflationary pressures have not abated, and there is little evidence they have, then it won’t matter that this domestic manufacturing slump has already reached thirteen months. Europe’s is a year longer, two years in total, and only now is it getting real.

While we are dealing with January figures here in both retail sales and industrial production they are largely virus-free. There isn’t any indication China’s pandemic has produced any major impact on the domestic US economy. Whatever weakness is indicated, and it’s not especially bad right now, nor in any way good, it does appear to be organic (for lack of a better term).

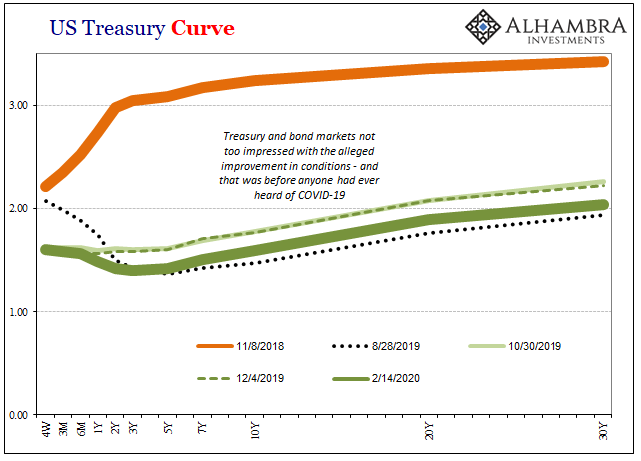

As I’ve stated before, I think that’s why you are seeing in the bond market behave cautiously despite so much good news noise (trade deals, rate cuts, record high stocks) and why the various curves (including WTI) are and remain so alarmingly distorted. Everyone keeps saying the COVID-19 outbreak is a risk to an otherwise improving situation, but the evidence says something else.

The situation hasn’t actually improved, has become significantly more questionable than even last summer’s recession scare, and thus any fallout from China is more likely to contribute to an already bad situation potentially making it that much more negative.

It doesn’t look like the virus is threatening to take away from renewed global economic tailwinds, rather the data (and the bonds) shows the risks are where the virus ends up being just another headwind on top of continuing, ongoing disinflationary pressures. Therefore, like trade deals, even if the coronavirus ends up being little more than a clickbait those will still remain regardless.

Stay In Touch