Like a shark smelling blood in the water, I don’t care that the blood is in the water from leaking out of what will be a dead horse, if it isn’t deceased already. I pretty much intend to beat on it one way or another. The issue isn’t just fed funds, it’s why anyone cares about that market at all in 2019.

The answer, as even FRBNY admits this week (the dead horse), is how the monetary world is much more complex than you’ve ever been told. It’s not just a matter for correcting textbooks.

In school, college or earlier, it’s all very simple. The Federal Reserve as a central bank being central will move money rates around at its whim. As Ben Bernanke said in 2002, it possesses this thing called the printing press.

Only, in practice it’s mostly just bank reserves which are the primary mechanism. Using Open Market Operations (OMOs), through its Open Market Desk situated in its New York branch the central bank adds or removes reserves as required to make sure the federal funds rate obeys the monetary policy target(s).

What they never told you was how the Federal Reserve hadn’t really done anything like that in decades. Ever since monetary authorities gave up on targeting reserves, instead targeting the federal funds rate, there have been practically no OMOs and practically no reserves.

The bank reserves didn’t show up until 2008.

Instead, what really happened was the market moved to the desired target (plus or minus only a few bps) because those participating in it thought the Fed could move the market if so desired. This was what don’t fight the Fed actually meant. It all worked because everyone believed it worked. Therefore, monetary policy had grown stale based on that one precarious assumption.

One of the primary (and early) revelations in the hot summer of 2007 was this “other” channel for US$ funding. As I recalled earlier, so much of what was really going on wasn’t going on in federal funds. So, it was a situation where the Fed claimed to be able to efficiently target money rates via a moldy, anachronistic tool it never used in a market far less central than anyone had bothered to check.

This is the point where current Chairman Powell’s recent testimony truly applies.

So monetary policy hasn’t been as accommodative as we had thought.

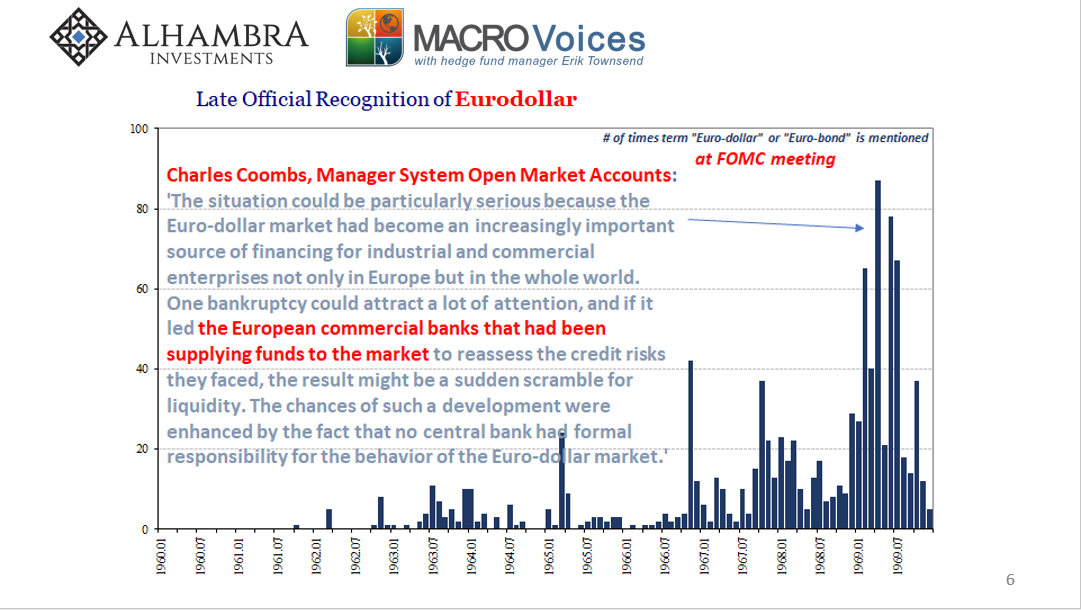

One of the major, if not the most major, fault lines which opened up starting August 2007 was perhaps the first piece of the eurodollar puzzle. Going all the way back to its earliest days, and recalling Milton Friedman’s excellent description of the process written out in 1971, banks located domestically would open a eurodollar channel by setting up a foreign subsidiary in a money center which, essentially, looked the other way.

I’m often asked why, for example, London had grown to be one such money center and the preeminent one at that. The simple answer was that in the dying days of the British Empire (the fifties and sixties) the English wished to hold onto something. Having established a banking empire as robust if not more so than its political equivalent, why not keep the monetary center of the universe in the UK’s capital city?

If sterling wouldn’t be acceptable, and it increasingly wasn’t after the Suez debacle, London could trade in dollars. To attract capacity, British regulatory authorities simply decreed that any bank setting up shop in the City of London (a separate zone within London) would be exempt from most if not all banking regulations so long as their customers were not British citizens.

You want to expand your balance sheet as you see fit, and offer whatever interest rate you wish in the process, go ahead if your clients and customers are all foreigners.

Other money centers followed suit, and then eventually by the end of the 1960’s US banks got involved – the subject of Friedman’s diagnosis. There were dollars out there in the rest of the world that US banks wanted, too, especially given the harsh(er) monetary regulations onshore. Screw Regulation Q.

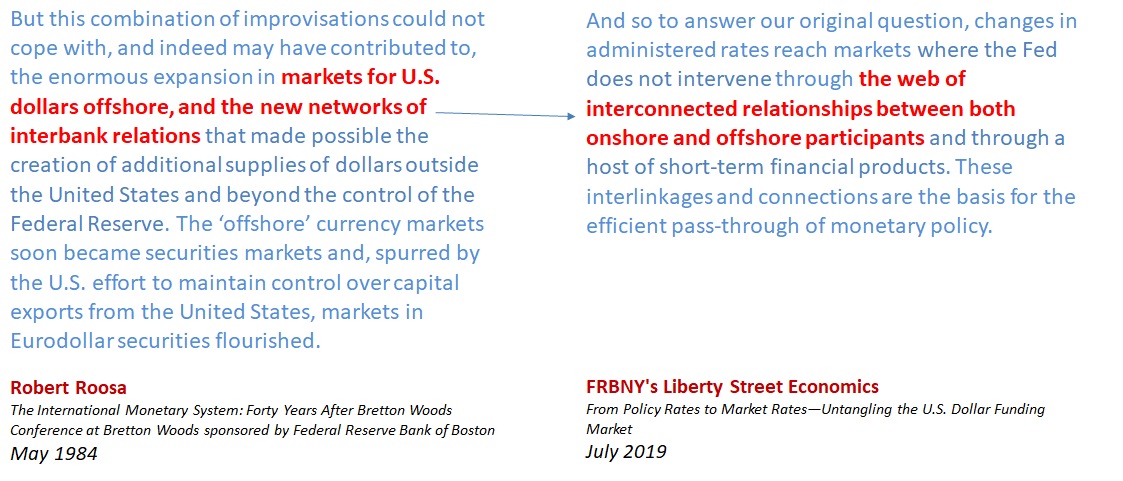

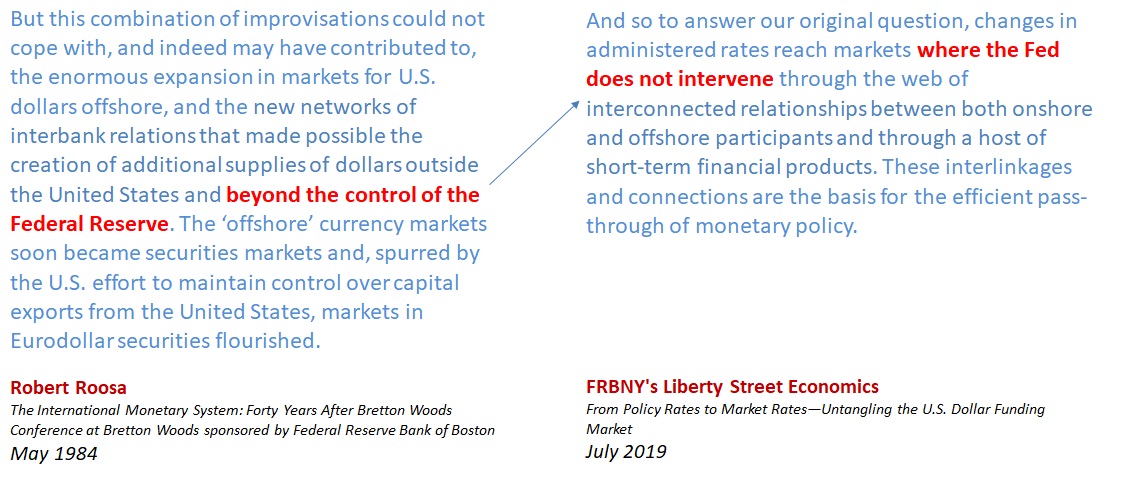

Thus, there was a robust channel between New York and London, and not only London. Offshore and onshore. The more it grew in size, the more it gained in scope – qualitative expansion as much as quantitative. What Robert Roosa had by 1984 already described as “new networks of interbank relations.” By then, these already spanned the globe.

It was chiefly these things which broke down beginning on August 9, 2007. Suddenly, out of nowhere, geography mattered. The difference between offshore and onshore became paramount.

Meanwhile, as if to prove the point, the clueless FOMC went about with rate cuts still believing their long worn out fiction; the threat of OMO’s and all that. They even upped the ante several times actually using them, first TAF’s, then dollar swaps, finally a whole host of other programs which were all equally useless.

Even then, there was some hope following what developed into an uncontrolled implosion particularly along these offshore lines. In 2009 and 2010 up until May 2011, some of that robustness back and forth regrew. But with Euro$ #2 came the final realization that this thing, this eurodollar system as it had existed for decades, just wasn’t stable.

No number of QE’s was going to fix it because this wasn’t really about subprime mortgages or Greek bonds.

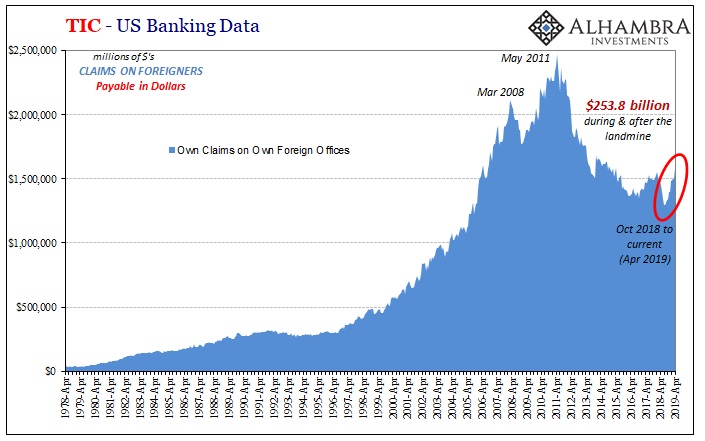

With all that in mind, we’ve witnessed some remarkable changes ever since last year’s October-December landmine. Not only do these numbers confirm it, they put a weirdly troubling spin on it before giving us a sense of its scale.

What’s presented above is exactly what I’ve been writing about here – the direct link between banks in the US and their foreign subsidiaries (offices) operating in various eurodollar markets (starting with London). Dating back to and including October 2018, these domestic firms have shoveled a quarter trillion to their overseas subs.

A quarter trillion.

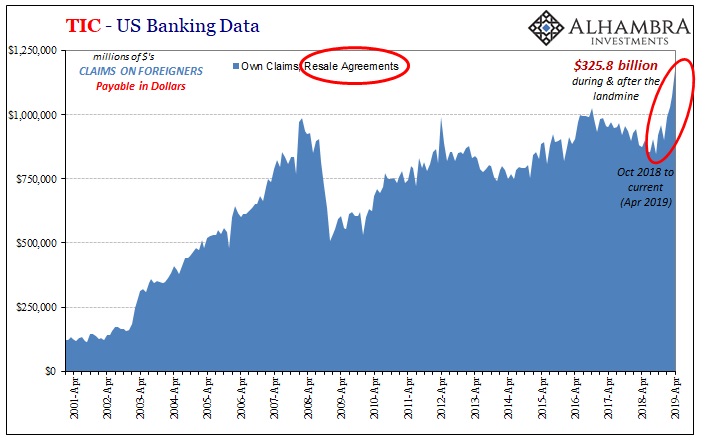

That’s not all. As I pointed out a few months ago, there’s also been an unbelievable amount of repo activity (therefore demand for collateral) heading out beyond the US border, too. The way this is accounted for in TIC, Treasury calls them “resales” rather than repurchases (the perspective of the cash).

That number is equally staggering, more than $325 billion during and after the landmine. Altogether, that’s a mindboggling $580 billion!

As I wrote back in April:

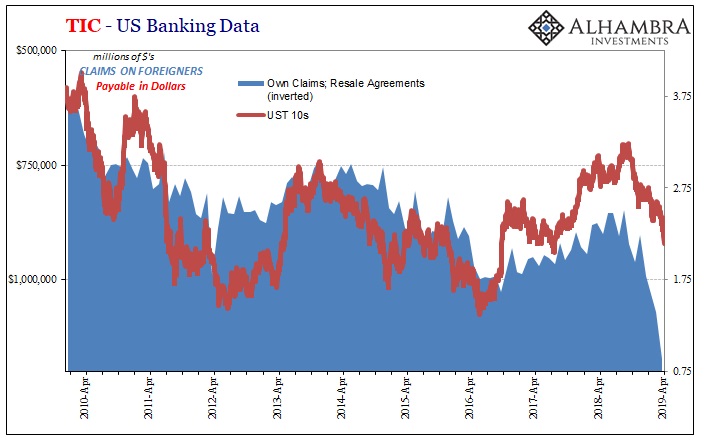

Given what we know went on during that period [the landmine], as well as its consistency with the same pattern over the years, it’s reasonable to infer offshore eurodollar tightness bleeding into demand for domestic resales. Increased cross-border repo would further suggest strong worldwide demand for safe assets particularly since last October.

More to the point, meaning broader than just repo and UST’s, are we encouraged that US banks were willing and able to shotgun more than half a trillion in US$ funding to both their foreign subs (most likely to be redistributed) as well as the wider eurodollar funding market, or are we very, very concerned that there is, up to this point (meaning April), an almost $600 billion hole which has opened up and persisted in those same markets since last October?

Taking the latter approach, that’s the only difference between 2019…and 2008. Unlike during the Global Financial Crisis, in 2019 the channel between offshore and onshore remains open.

What if it doesn’t?

Even contemplating what right now is only a possibility, you might be more than a little nervous about how it is a very real one. Especially if you are knee-deep in offshore funding risk. I’ve asked before, what is it that must be spooking global dollar and bond markets right now? Here’s at least part of the answer.

The other part would be another question. What would force that onshore/offshore channel to narrow or even close up like it did twelve years ago? Perhaps something to do with one or several German banks?

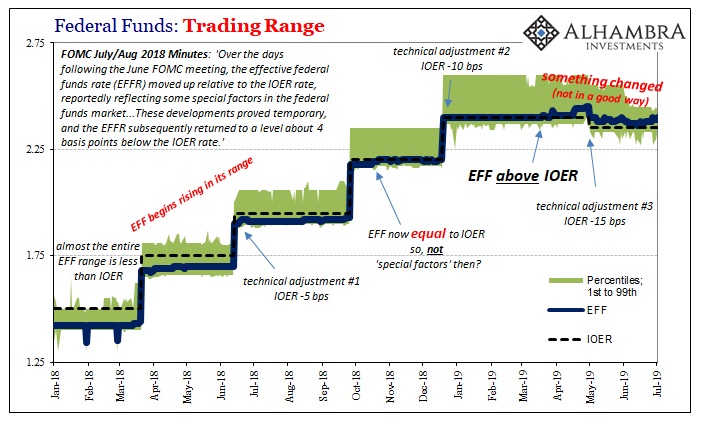

Which brings us back to the dead horse. Something is going on in funding markets. We’ve actually known that since early last year, via federal funds of all things. As you can see above, the Federal Reserve has no idea what that something is. First it was T-bills or “special factors” which the FOMC claimed last summer would only be temporary.

Once it was shown to not be special factors nor temporary, then it was technical adjustments to IOER to get things back under control. Except, that something changed again very obviously and dramatically around March 20 – the day EFF broke above IOER (the joke).

Now, all of a sudden, the Fed at its New York branch wants to write about the high complexities of these US$ money markets and further how though they’ve never said much (really anything) before there’s actually a lot going on between offshore and onshore dollar connections – that they further imply you shouldn’t be worried much about. Sure, because you guys have done a bang-up job this last dozen years.

I don’t believe it is just disinflationary numbers which has got Jay Powell’s current attention, and which is pushing the FOMC to start cutting rates in just a few weeks. If there is genuine reluctance and uncertainty as it relates to global dollar liquidity, there are already enormous reasons behind it.

New York central bankers finally come out and admit offshore dollars are important, that they must play some fuzzy role in things, but don’t yet grasp just how important.

The markets may be worried that officials will be forced to recognize and reckon just how important before much longer.

Stay In Touch