It was late on a Friday night in early September 1997. Because his speech was given at Stanford University out in the Pacific Time Zone just as the weekend was about to commence, market watchers were bated with an almost frenzied anticipation. Alan Greenspan had come to be seen as more than just a monetary policy bureaucrat. He had conquered the bond market with his 1994 massacre, and was leading, nay, controlling the entire US economy with such skilled input it was the very example of simple elegance.

Not even a year before showing up on the West Coast, Greenspan had captured everyone’s attention with those two little words. It was only December 1996 when he uttered “irrational exuberance.” At the time, everyone thought he was talking about the stock market. People today still believe that.

With visions of bubbles fresh on everyone’s mind, the Asian flu and LTCM not yet clear enough over the close horizon, the Wall Street media expected the Federal Reserve Chairman to deliver another doozy. With markets long since closed that day, and two whole days until Monday, he was free to be less, well, Greenspan. Perhaps he would set aside the Fedspeak at least for one minute.

Instead, the speech he gave was mostly about monetary statistics. Milton Friedman was in attendance, and the big debate of that age wasn’t dot-coms it was rules-based policy. Some like Friedman criticized the Fed for just winging it; they were constrained only by imagination, which many saw as a dangerous proposition.

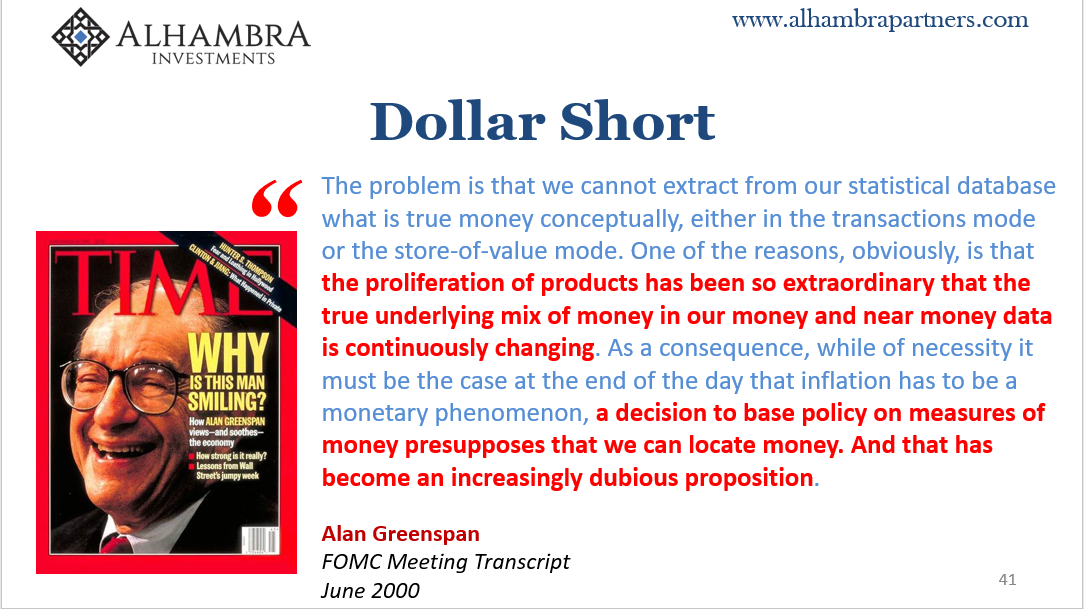

Forgive us, Greenspan said, how else are we supposed to conduct ourselves?

Increasingly since 1982 we have been setting the funds rate directly in response to a wide variety of factors and forecasts. We recognize that, in fixing the short-term rate, we lose much of the information on the balance of money supply and demand that changing market rates afford, but for the moment we see no alternative. In the current state of our knowledge, money demand has become too difficult to predict.

That’s not how it was translated into the public, though. The New York Times speedily wrote up its own version of the maestro’s speech for publication early on Saturday morning, September 6. Such was the demand for this guy’s opinion.

Mr. Greenspan discussed how policy makers had abandoned as formal guideposts predictors of inflation like gold prices and money supply figures when it became clear that the changing nature of the economy had made them less meaningful.

That right there is how this mess got started: “the changing nature of the economy.” Nope. The economy fundamentally is still the economy. How it operates and works deep down at its core is the same stuff economists and laypeople have been arguing over since humans first realized there was such a thing. The format of output might be very different, technological changes and whatnot, but economic processes are perhaps the only thing immutable here; supply and demand curves still work very well, thank you very much.

What changed was money, not economy. Even the article’s headline blows it: Greenspan Voices Doubt On Statistics. Again, no. What the Chairman said was, we can’t make sense of money demand any longer. The data we used to use which matched real world observation had long, long ago been rendered obsolete. The monetary system evolved but the statistics never did.

That’s an entirely different proposition – for a central bank, no less. In response to Friedman, dear Alan explained they had forsaken all hope of a money-based regime and readily accepted this other approach. We jigger the federal funds rate a little bit here or there, and the economy is awesome as a result. Therefore, we must know what we are doing.

This is the rule everyone easily fell behind!

Except, they didn’t know causation from anything, this was just assumed from the correlation to this Great “Moderation”; that fed funds kabuki was the primary reason for it. Only, as irrational exuberance was meant, maybe that moderation itself wasn’t established, either. In other words, we can no longer define money, and since we can’t measure it we’ve radically altered our approach which seems to be working but there are a couple of warning signs we may want to pay attention to.

As we all know, as the years progressed rather than pay specific attention to these shadowy dissents, officials would plead deeper and deeper ignorance. The warnings didn’t dissipate, they got bigger and bigger. This explains the official silence.

So, here’s the big question of all big questions. If they didn’t know enough about modern money such that they completely abandoned its use in setting policies, how could they know when there might be a problem with modern money? That actually comes first before thinking about what might be done.

It’s a rhetorical question, one which no one is meant to ever consider. Certainly not under an expectations regime which depends upon you blindly believing each and everything a central bank does. Monetary policy is powerful simply because everyone believes monetary policy is powerful.

Some, however, might ask: is it really? And people may contemplate that very question without ever realizing that’s what this is all really about.

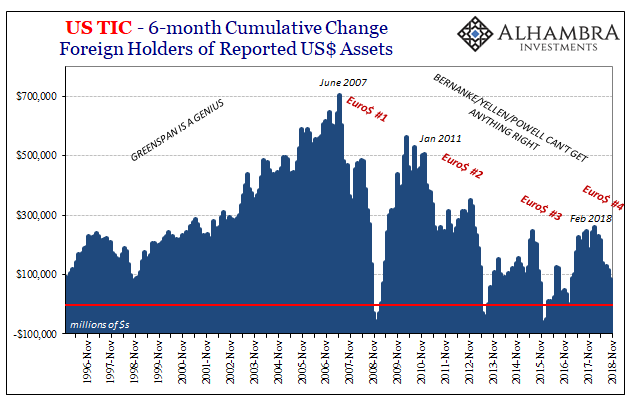

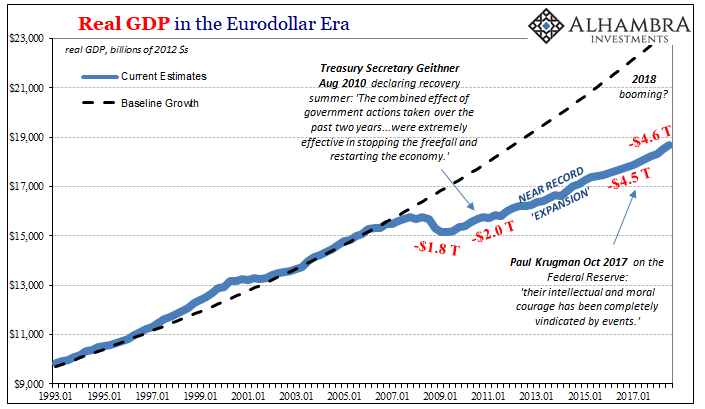

Trillions in “money printing” and now nearly five years, half a decade of talking non-stop about “full employment” supposedly created by it. These two alone are supposed to be ungodly flammable in the context of consumer price inflation. An increasingly sharp labor shortage plus an out-of-control printing press flooding the world with liquidity!

And yet, nothing. In terms of inflation expectations, barely a blip. Even globally synchronized growth in 2017, didn’t really move the needle.

Two decades ago Alan Greenspan was already talking how it had been nearly two decades since they could try read money demand and supply let alone do something useful with them. That’s not what everyone heard, though. They got irrational exuberance and some mild discomfort over statistics.

I wrote last week:

This is one key factor as to why our economic problems are so hard to overcome; how in the world the global economy can lose an entire decade and be one-tenth of the way into another. You start by saying the central bank isn’t central and already people are at best skeptical if not completely turned off. And then you tell them, the few who are left, if you really want any chance at legitimate economic recovery Goldman Sachs needs to make more money, a lot more, in its bond trading business. And if you don’t want Goldman to thrive in FICC, then the whole global monetary system must be completely revamped from the ground up.

Oh, and by the way, we’ve been operating under a clandestine global monetary system predicated on the world’s biggest banks who aren’t really banks working in the shadows for half a century already.

It’s way, way too much to grasp, especially all at once.

The good news, a small silver lining, is that stubbornly contradictory inflation expectations show how people do grasp the symptoms even if they might not yet be ready for the full, comprehensive explanation. They know something’s not right, still even in 2019 not quite right, lacking the full picture start to finish. At some point, the public just might be open to finish what Greenspan’s careful dodge(s) would’ve started had he the courage; what was really behind irrational exuberance (and I don’t mean the stock bubble).

That’s the unfortunate part. This is a conversation that should have been started, and completed, in public in earnest a very long time ago. I shudder to think of the eventual costs that might have to be absorbed and for what? In one very important sense, the dot-com bubble was far more damaging than just what it did to the NASDAQ. For an entirely too brief of a period, a public discussion about monetary evolution was at least possible.

Greenspan, to his everlasting shame, stopped talking about it the higher share prices ascended. Once they crashed, the topic was banished altogether. The silence has been deafening.

Stay In Touch