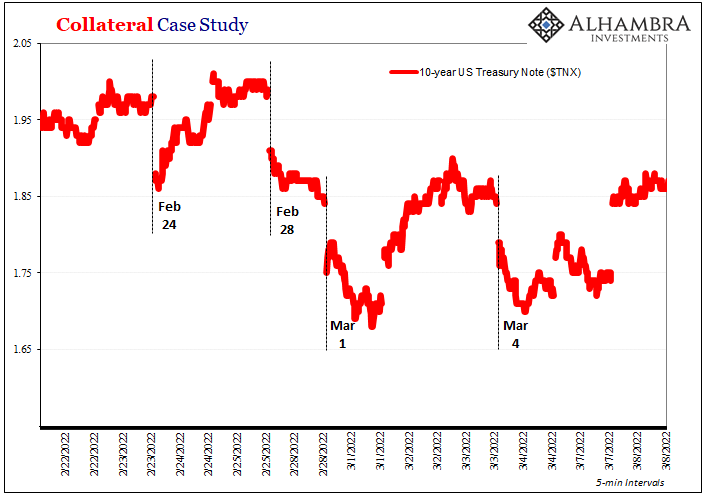

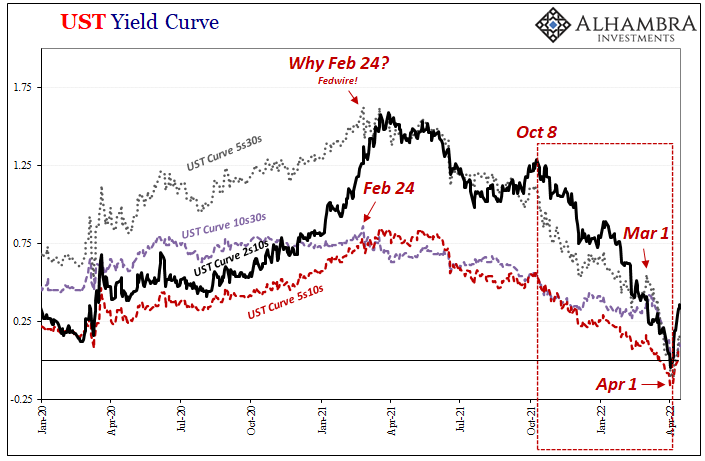

If there was a compelling collateral case for bending the Treasury yield curve toward inversion beginning last October, what follows is the update for the twist itself. As collateral scarcity became shortage then a pretty substantial run, that was the very moment yield curve flattening became inverted.

Just like October, you can actually see it all unfold.

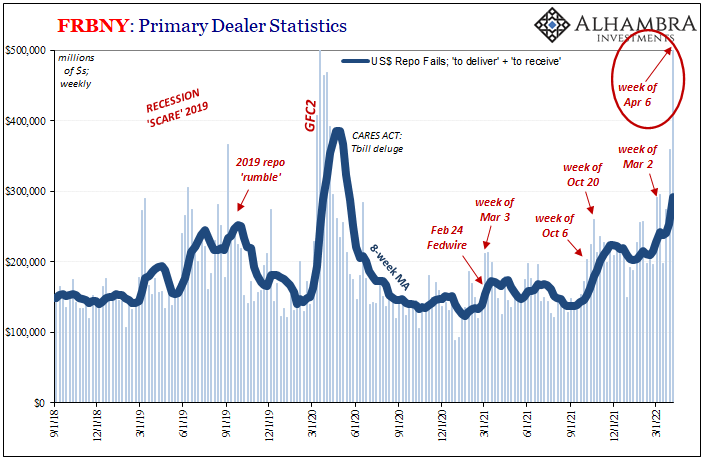

According to the latest FRBNY data taken from Primary Dealers, repo fails during the week of April 6 (most recent figures) were a whopping $507 billion combined (remember, an unknown proportion of fails, likely a huge chunk, in my view, is due from failed collateral for collateral swaps). This is the highest since the worst week of GFC2 in the middle of March 2020, the second worst weekly total in more than four years; that’s how bad deflationary potential has gotten.

But it’s not deflationary potential, is it?

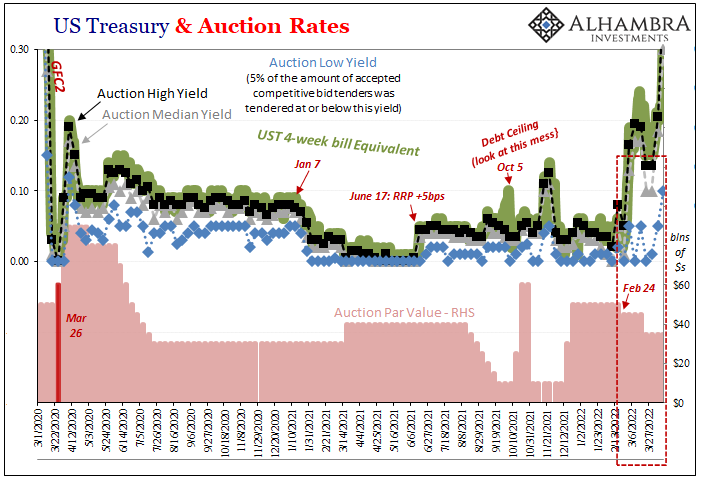

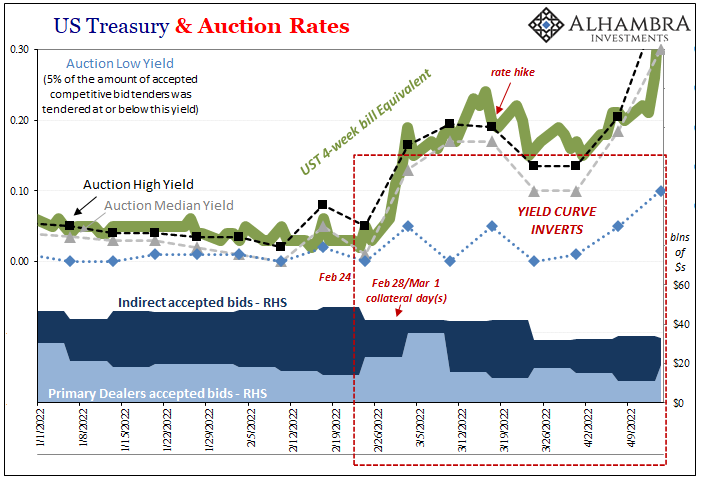

These same weeks going back to late February/early March when the 4-week T-bill has stood out front and center (as I’ve pointed out repeatedly). The Federal Reserve’s rate hike effective March 17 had only further exposed huge demand for the 28d bill. It had priced consistently to yield way below the RRP rate, proving extraordinary demand for the instrument separate from investment characteristics meaning collateral shortage.

Even before March 17, the same bill was already exposing this deficiency in earlier auctions. Right from the start, February 24, the Treasury Department has been again cutting back on issuance, squeezing supply and availability for especially dealers who then transmit the deficiency across the entire financial landscape in a dampened liquidity environment more broadly.

It was during that initial cutback by Treasury, the last week in February, when, amidst the invasion of Ukraine, we found our collateral day(s). Almost certainly the combination of these several factors: uncertainty about the war, another devastating spike in oil only raising further prospects for global demand destruction, combined with suddenly fewer available bills (and the foreknowledge how this squeeze was going to be made permanent; see: TBAC reference below).

This clearly had triggered a scramble for collateral among dealers, if not an outright run. The aftermath of which continues to this very day (as pictured in still-intensifying repo fails).

The dealer bids at these auctions clearly outpaced indirects in this period. The indirect bidders, mostly investment funds, have been getting less of these auctions since they are increasingly unwilling to pay a high price for bills given prospects for immediate rate hikes (therefore alternative, higher-yielding investments elsewhere). Since it isn’t indirects, that means it has been dealers paying what are essentially huge liquidity premiums.

They’ve been dragging down the low and even median prices at each of these bill issues. See for yourself:

The same dealers who either profit from, or are themselves at the mercy of, the collateral scrambles and runs. Either way, they’ll pay the huge premiums. The March 3rd auction of 28d, for example, the auction just after the collateral day(s), the low suddenly just 5 bps well below the median of 13 bps and 19 bps in the secondary market.

By the middle of March, more repo fails, even more high-flying dealer bids for the 28d bill – to the degree it pulls down yields across the entirety of both those auctions (March 24 & March 31) from low through the median to the highs, visibly below secondary markets even as those secondary market rates were themselves substantially beneath (the raised) RRP.

Those particular two weeks (marked above as YIELD CURVE INVERTS) the Treasury yield curve was at its most extreme (so far) inverted depth as well as breadth. The 2s10s spread was overturned on two days, the worst April 1. Similarly, the 5s10s were inverted between March 21 and April 8, with the heaviest distortion in that key calendar spread April 1st to 5th.

This time, as opposed other times last year, Treasury is scaling back on bills because the government is simply borrowing less. Officials aim to keep total bill issuance at around 15 to 20% of total debt; less overall debt, fewer bills sold to collateral-starved dealers because the government doesn’t factor effective, useful money (neither does the Fed).

Ironically, the dealers have told Treasury they are just fine with this (or, specifically, the people working at Primary Dealers Treasury listens to via the TBAC, or Treasury Borrowing Advisory Committee, who apparently, unsurprisingly, aren’t up to speed on the monetary importance of T-bills). The system in reality obviously is not, though nobody knows or cares outside of it.

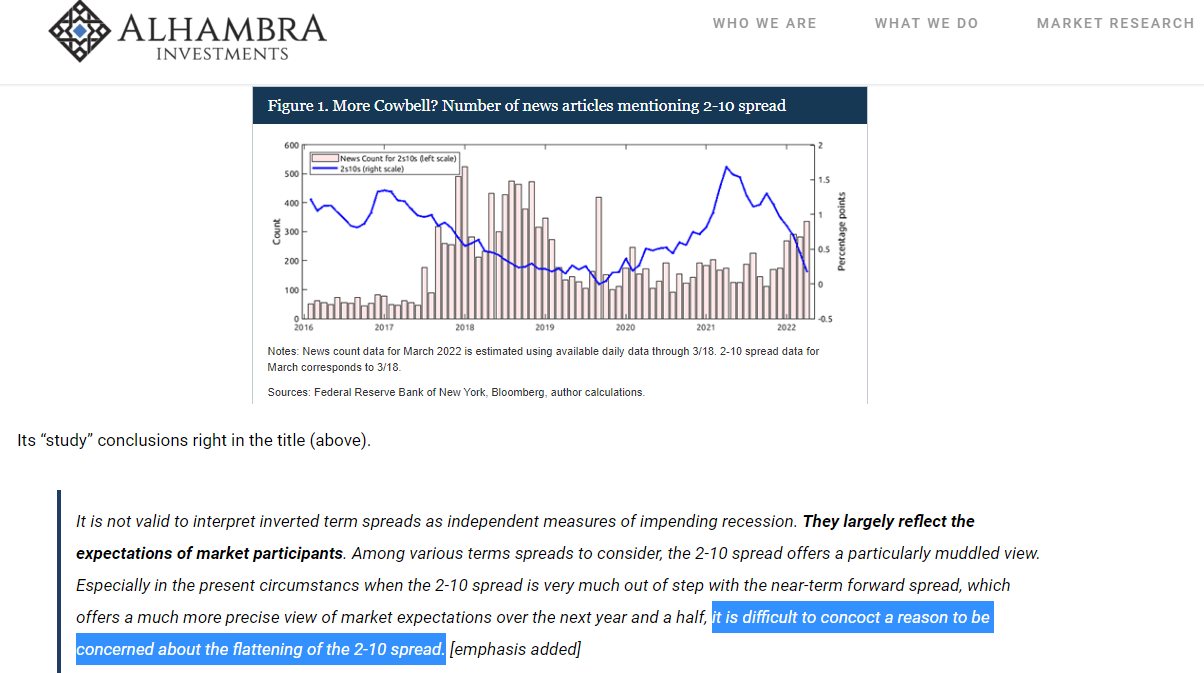

Is it difficult to concoct a reason to be concerned? Yes, if you work for the Fed because the Fed doesn’t do money, or even realize how money collateral is or can be.

The result has been a serious contribution of very real deflationary money, not just potential, which coincides exactly when the yield curve (and eurodollar futures) triggered. I have zero doubt whatsoever this is mere random coincidence.

Not only is there a direct relationship between demand for collateral of all kinds when supply changes, when the multiplier for all collateral drops, the demand for general safety and liquidity rises in relation to every other factor or consideration including front end rate hikes. As I always write, it takes a hell of a lot to overturn a money or bond curve, to get it out from its upward sloping shape.

As you can see collateral-wise, it was indeed quite a lot.

Further, Fisher (as in, Irving). Actual and very severe outbreaks of deflationary currency only further reduce growth and inflation potential over the long run, the very fundamental factors driving LT UST yields again relative to ST yields being influenced by, in this case, anticipated rate hikes.

From October last year with flattening on through March and April this year with inversion, behind the whole trend is collateral (not the Fed). Beside dealers and auctions, what are the likely consequences? The reason we call it deflationary currency is because it almost certainly exerts a (further) deflationary force on everything from financial markets (maybe even stocks?) to the real global economy (ahem, just where is China’s financial money?).

This indicates that what is inverting the curve is not an effective Fed regime of rate hikes about to tame “inflation”, engineering a soft landing as many want to imagine, rather a much higher probability for those other more direct and macro consequences.

The yield curve today is mostly un-inverted, except for that crucial 7s10s part. All good again? No. Even these curve dynamics are volatile, where the market often inverts the thing, un-inverts it, then re-inverts it again down the road.

That it happened, and that it happened in some huge part because of a very clear collateral run, the likelihood we’re going to be seeing more of everything in this deflationary bucket in the near future is far, far higher than the current CPI.

Stay In Touch