Inside the Treasury Department, the Office of Financial Research has grown to 225 employees, though that may be just a concerning (bureaucracy) as it is laudable (serious effort). Incorporated by Dodd-Frank, the agency inside the agency is dedicated to “Wall Street Reform”, at least that was the heading upon its old website. At its new virtual location, OFR projects its mission as, “established by Congress to serve the Financial Stability Oversight Council, its member agencies, and the public by improving the quality, transparency, and accessibility of financial data and information; by conducting and sponsoring research related to financial stability; and by promoting best practices in risk management.”

In fact, OFR has been one of the few sane voices in an otherwise byzantine mess of over-regulation and contradictory (and counterproductive) systems. The OFR’s research, which I have referred to before, actually seems genuinely concerned and, more importantly, capable of at least outlining the contours of the modern banking and financial system. They have been warning about system liquidity factors, even ironically related to Dodd-Frank itself, for some time.

Their latest offering is pretty much more of the same, with the exception of having moved from theory to fact. October 15 remains a marker about that which is not spoken much by central banks, economists and especially media commentary. The reasons are simple, as they make plain about their own conclusions – as this unambiguous title in the Wall Street Journal shows, US Watchdog Sees Risk of Repeated Liquidity Crunches. Such an exclamation is so contrary to the “narrative” that it must be given as little attention as possible.

The prominent picture at the outset of the article is certainly intentional, as the side shot of Janet Yellen leaving a meeting with the director of the OFR suggests cooperation in only the superficial of manners. It is Janet Yellen who had (not so much recently) used her inauguration “honeymoon” to proclaim repeatedly how “markets” are now so “resilient” thanks to nothing but central bank prowess.

That, of course, amounted to nothing but wishful thinking, or rather owing to her subscription to rational expectations theory, projection. The details in the OFR report are strikingly similar this year to last:

One reason for the decline in liquidity is that banks are less willing to facilitate trading as new regulations make lending cash and securities more expensive. Regulators have said the rules are necessary and will reduce the kinds of excess borrowing that fueled the 2008 financial crisis.

This remains the bedrock assumption about the deficient state of liquidity in the “dollar” system, and not without good reason. Dodd-Frank and Basel III have a combined effect in that manner, and offer some specifications about why liquidity problems have occurred but not when they occurred. The liquidity problems in 2010 and 2011 are obvious, related to the euro crisis (which was, again, as much a “dollar” fragmentation as anything), but why the massive selloff, especially in MBS, in 2013, and then the repo-directed dysfunction leading up to October 15, 2014? The timing of each episode is highly curious and relates to nothing about Basel or Dodd-Frank apart from a distant and general baseline.

Instead, monetary interference is the only plausible interpretation. The sell-off in 2013 was initiated by threats of simply “taper” which by itself should have been almost fully innocuous. The asymmetry of the spark and then the following conflagration is very revealing. The real problem, unambiguously bearing out in derivatives (and the follow-on collapse in bank FICC), was how monetary policy pushes a one-sided trade and then to its extreme.

The mechanical culprit of such illiquidity is the lack of front-line defense, once offered by dealers:

A reduction in securities that are available to lend against in financial markets—such as Treasury bonds and asset-backed securities—also is fueling the volatility. The securitization markets have shrunk since the financial crisis and the Federal Reserve has further reduced the amount of available securities by snapping up trillions of dollars in bonds in recent years.

This is, in the sense of the last sentence above, a radical shift in admissions. The Fed and the entire bureaucratic apparatus had denied, consistently and vehemently, for years on end that QE had no such downside effect. In June 2013, then-Chairman Ben Bernanke testified to Congress in the middle of the most violent portion of the selloff:

But our assessment—and, of course, we’re in that market quite a bit, so we have a lot of information about it—our assessment is that that market is still working quite well, and that our purchases are not disrupting the normal price discovery and liquidity functions of that market.

Translation is obvious, meaning that QE did not disrupt collateral flow nor did it dissect dealer proclivities toward vital action. Except none of that was true, and none of it has changed except that “they” are now willing to admit what was obvious.

But, again, QE stripping out collateral is not the whole story, nor is heightened “capital” expense of banks maintaining inventory. Sometimes the most obvious aspect is the most difficult to see and admit because it contradicts everything that you hold dear. Orthodox economists are wed, welded even, to the idea of monetary neutrality, thus a decline in systemic liquidity due to QE and QE-type behavior on the part of the central bank violates that fact in a manner far too close to home.

Dealers were willing to hold major inventory, especially in the age of ZIRP, because they took the Fed’s “wink” promise that rates would be held low “forever” and that meant one-way price direction. Dealer inventory is not the only factor to consider, as hedging and derivative risk functions are as much relevant to systemic liquidity as any bond inventory quantification. The concept of “holding and absorbing risk” relates to a myriad and complex webbing of financial concepts, especially portfolio and Greek risk.

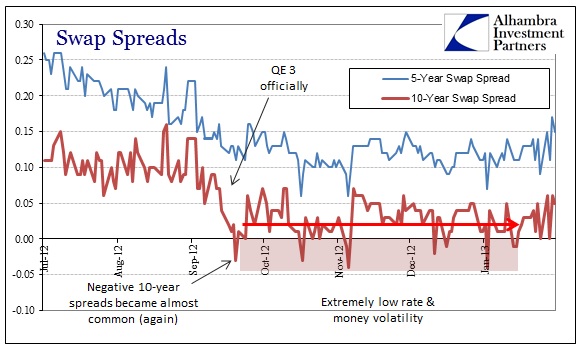

Dating back to QE3, dealers went rather insane all in the same direction, writing interest rate swaps (in other words, taking floating and receiving fixed) to the point that swap spreads, especially in the very important 10-year segment, dropped negative again.

If you take the Fed’s actions with QE 3 (and then 4 in December) as an explicit extension of Bernanke’s promise to keep rates low not for discrete periods (as in QE1 and QE2 with predetermined end dates) but something closer to permanence, there would be vast profits to be made on anyone daring to bet (or hedge) for higher rates. And so they did; dealers all got in the same direction.

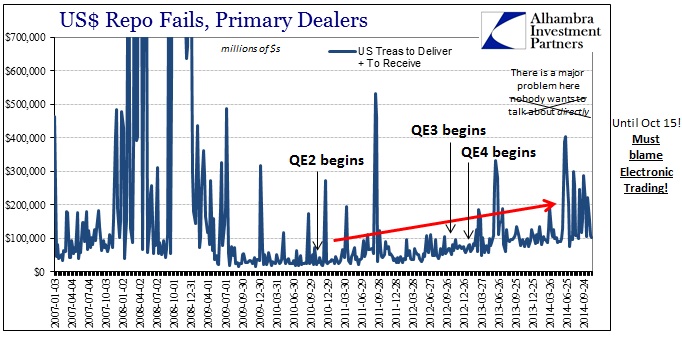

It all started to go awry in March 2013, but by May’s introduction of the taper concept, risk absorption was seriously impaired because of that positioning. When everyone is trying to lay off risk on everyone that is already fully risked in the same exact direction, there is no systemic mechanism to derisk. It wasn’t just about bond inventories, but rather the capability of the dealer system to extricate itself from the crowded trade – a crowded trade (that includes buying MBS in the first place, with QE3 weighing on production coupons making MBS prices “only” appreciate) delivered exclusively by QE itself.

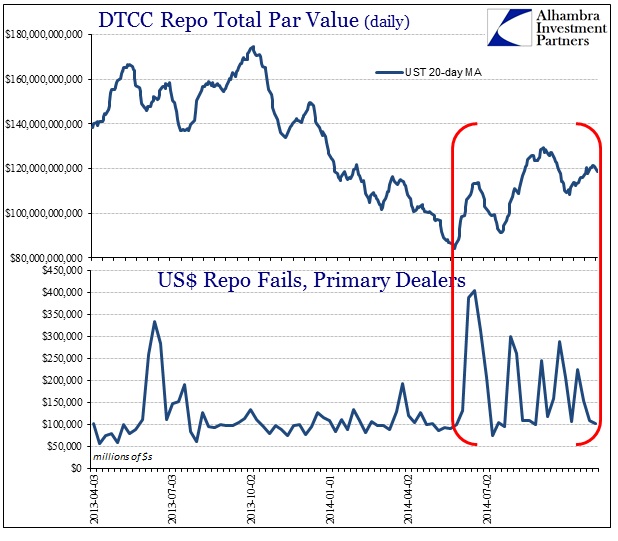

I have made numerous references to the repo market since the middle of 2013, tied directly to bank “resources” directed at FICC including MBS. In other words, after that 2013 selloff finally abated, banks packed up and left – permanently. Repo volumes dropped representing nothing more than the withered state of liquidity capacity; they got burned once and were not going to stick around and get nailed again. Once tested in June 2014, for all the various and sundry global dollar short reasons, such limited capacity strained for weeks and weeks before finally breaking out on October 15.

The OFR is doing very good work in actually bringing this issue forward as best it can. While that is a big positive, I still would rather see them push beyond the narrow confines of convention. Unfortunately, even the OFR may be too vested in the orthodoxy to suggest as much, especially given that the current director, Richard Berner, was a “top economist” for Morgan Stanley. That plus the bureaucratic tendencies which are always going to be present (you have to really wonder what Janet Yellen was saying to Mr. Berner in their meeting) perhaps limits how far they will go – the OFR might be good at describing factually what is taking place, but bureaucratically unable to draw the proper conclusions, make the full implications, and thus render anything like judgment beyond what government is comfortable with.

Regardless of all that, the true implications of even their work thus far in this area is the recent theme of how QE is far more destructive than ever imagined, which is a fact that is only now being recognized and admitted by even the same people that thought it up and used it. Their warning is an extrapolation of what we have already seen, namely that there were serious problems under benign conditions. The OFR is saying that these liquidity episodes are likely to be repetitive, including circumstances that are far more dangerous. As with so many other aspects of economy and finance as 2014 draws to a close, you have been warned.

Stay In Touch