Under the traditional formula for viewing currency movements, a rising currency is believed to be a huge impediment for economic expansion as exports “become relatively more expensive” against trading partners and competitors. This is a two-dimensional view in three-dimensional space as it leaves out the very necessities of finance. It isn’t just straightforward that one causes the other, as the rising or sinking currency itself may be instead related to financial irregularities that have nothing to do with trade.

If the currency relationship is more complicated, then so is any policy intended to address it. Such is the case with China where the “peg” to the “dollar” has left the yuan, in many people’s estimation, rising too far. In offshore trading, the yuan has devalued somewhat against the “dollar” but only to the edge of what the PBOC will “allow.” In fact, the PBOC has reset the reference rate not in the direction of devaluing further, but as a menace almost against such a means.

Some have cautioned that the PBOC’s objective is to not allow too much instability into the currency, and thus the evident disdain for following offshore trading lower. However, I think this confuses cause and effect as instability in currency trading is itself incidental. Global finance has found China seriously on the “short” side of the “dollar” which makes the currency’s movements often counterintuitive to those anchored to only two dimensions.

“I’m not that pessimistic about China’s economy because the problems can be fixed and the policy makers are fixing them,” Larry Hu, head of China economics at Macquarie Securities Ltd. in Hong Kong, said by phone on March 12. “Lowering the reserve ratio won’t necessarily have an immediate impact on borrowing costs, but it’s a move to meet China’s structural change, which is declining capital inflows.”

That is a better expression of the problem but leaving out a vital element. Being “short” the “dollar”, even synthetically, leaves Chinese onshore banks and their offshore counterparties exposed to “tightening” in the eurodollar market. That is often expressed by a “rising dollar”, or, the flipside, a depreciating yuan. Given the PBOC’s attention to its peg, that leaves Chinese banks further exposed to finding funding alternatives in “dollars.”

One such alternate is the PBOC itself as the financial intermediary of the Chinese government’s vast holdings of “reserves”, including UST. That means the PBOC can “intervene” in “dollar” markets onshore to supply “dollars” if necessary; whatever to maintain the flow of finance in and out without major disruption.

This is further complicated by the fact that the PBOC under its reform umbrella clearly believes that “dollar” financing is partly responsible for its bubble imbalances. Again, the fact that they won’t follow in the devaluation trend is a major confirmation of that view; under the vernacular used in the quoted passage above, I don’t believe the PBOC is much bothered about “declining capital inflows.” In fact, I think they would prefer that situation as it would allow them to “direct” “dollar” flow more along the lines of their reform agenda out of their own sourcing.

If that is the case, then we would expect that the PBOC’s holdings of UST would change with their attitudes toward the “dollar” exposure in China and the growing attempt to curb bubbly speculation, both “dollar” and internally sourced.

There was the first major inflection during the mid-2013 “dollar” selloff, and then ever since “reform” became the primary objective Chinese holdings of UST have moved lower (accelerating in December and January). In other words, what you see above is exactly what you would expect of their “dollar” holdings given the three-dimensional setup of reform. The Chinese are not “selling” UST out of their portfolio so much as trying to intentionally replace marginal sources of “dollars” via their own “official” account. That would allow them to navigate the particulars of this shortage situation, which is dire not so much as a means of direct global supply but of the willingness to extend bank balance sheets in all directions with all proper risk mechanics.

This method of dealing with the short is not ideal, but that describes almost everything about China and the PBOC in 2015. So the yuan may trade in devaluation to its official reference, but you can almost be sure that there are domestic “dollars” on offer to keep it there and no further.

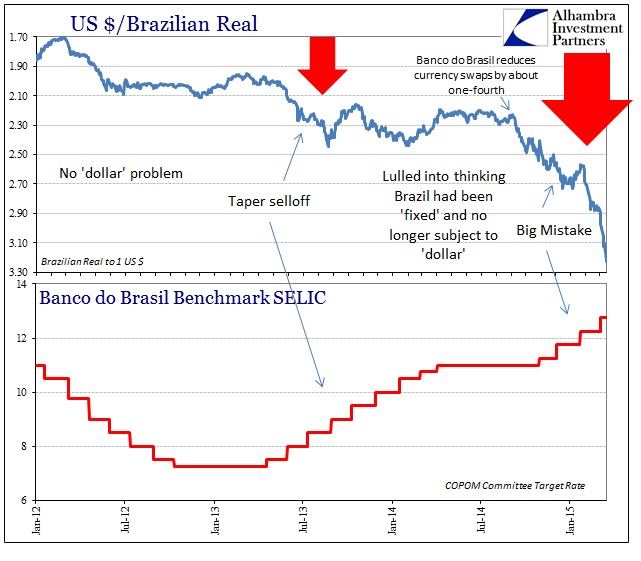

We can see similar behavior of other national systems in relation to their “dollar” holdings. Yesterday, I highlighted the internal system approach of Brazil as it related to the “dollar” and inflation. Banco do Brasil clearly believed, after suffering near meltdown in the 2013 event, that by the middle of 2014 it had been freed of the marginal restraint. Thus, the central bank put its rate hikes on hold and even went so far as to unwind swaps at maturities (rather than rolling them over; the Brazilian system is unique and the means of using the cupom cambial is highly inefficient, but not the “kiss of death” that actually mobilizing reserves would mean).

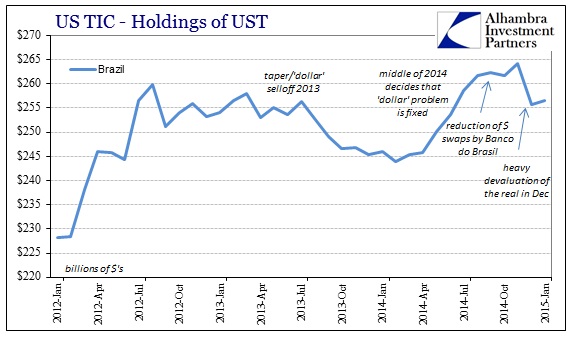

The marginal response of Banco do Brasil is replicated in the TIC data for Brazil.

Again, the declines in reported UST holdings is not so much “selling” UST as it is raising internal sources of “dollar” liquidity; indeed, we do not know whether such action took place in “official” central bank moves or the private banking system adjusting its own. What we get out of TIC is a blended national view, and then a globalized view of overall “official” response to the “dollar” condition.

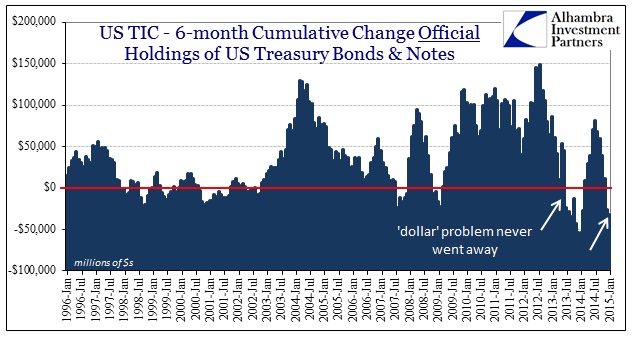

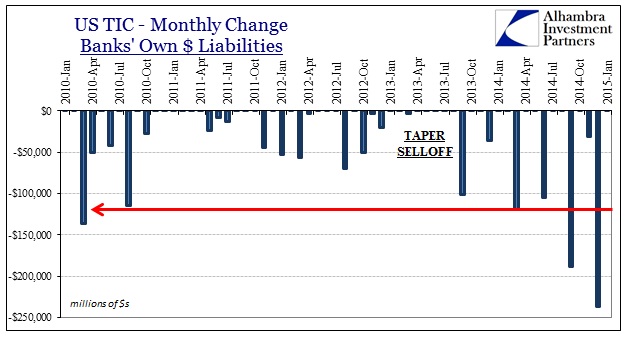

Given the massive “dollar” deficiency of October and then January, there are also no surprises here in official holdings of UST. Further, on a monthly basis, even private holdings were net negative confirming the “shortage” view of the global “dollar” during what was surely two separate liquidity events (October 15 and then January 15) expanding all over the world.

This heightened state of awareness in total liquidity is in sharp contrast to the pre-crisis period that was almost inertly stable by sheer force of eurodollar acceptance and growth. That would suggest as to why such relatively small changes in 2013 and 2014 have produced such asymmetrical results to the downside, as the entire global “dollar” system was altered irreparably it seems at August 9, 2007. What has transpired in the years since is a growing acceptance and realization that the predominant eurodollar system remains in that altered and agitated state. That would make financial considerations, in three dimensions especially, that much more difficult and uncertain.

Part of that paradigm shift has been in response to undoing US QE, which seems to have drastically transformed, not surprisingly, the “dollar” behavior of global banks. Part of that certainly relates to how they position themselves at and around quarter ends, revealing huge vulnerabilities in funding reliability that just should not be a problem (but seems to be clustered around every major liquidity event in recent history). In other words, the cumulative effect of this “dollar” transformation, owing very much to the heavy presence of QE and its effects on financial resources and considerations, has left global “dollar” liquidity in a very precarious state with little margin for error.

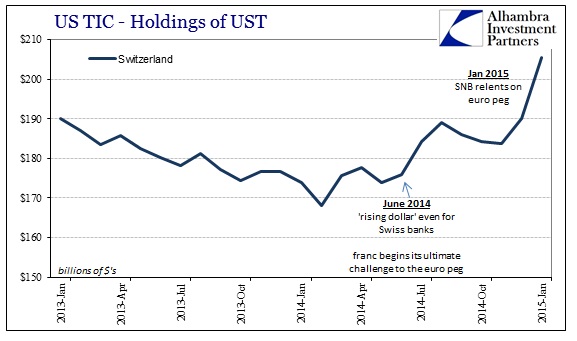

By that account, the end of quarters in September and then January saw massive bank shrinkages that exposed liquidity levels on many fronts – especially in currencies that were most vulnerable beyond China and Brazil (which, by way of the euro peg to the franc, included Switzerland).

In summation, while the FOMC dawdles about normalcy and the strength in the US economy, the rest of the world shoulders the burden of shifting global banking function that doesn’t apparently factor for Yellen and her fellow policymakers. Their primary mistake, the same they made so disastrously in 2008, was in believing that the dollar ends at the shores of the United States national boundaries. The FOMC seems intent on “tightening” if only to further the narrative of US recovery and strength, while the global “dollar” system is already there for the exact opposite reasons. As suspected, TIC flows demonstrate this dichotomy very well and how the rest of the world is trying to deal with it.

Stay In Touch