I believe the phrase that is attaining Paul Krugman all these invitations to “consult” on economic failure is one that he has used pretty consistently for years. He says “deflationary vortex” and for a long while it was ignored as studious monetarists were busy inflating away; except that none of them, from the Fed to BoJ to the ECB, even the PBOC, ever got there. Now, all of sudden, with “deflation” again apparent as the most significant danger, Krugman’s thesis sounds downright mantic. As a result, Krugman has been visiting everywhere from Japan to Greece to “consult” and crow about his version of failure.

This is not to say that Krugman, as the epitome of a neo-Keynesian saltwater spirit, is really divergent from these central bankers. Not at all; if anything, there is only a difference of degree. Neo-Keynesians are enjoined of monetarism which isn’t all that unexpected since they are both versions of central planning and top-down exercise of economic control. They only disagree on the specific levers of control and often the scale to which they are used.

So it was on January 15 of this year when Krugman was nearly apoplectic about what the Swiss National Bank did about the euro peg. He wrote a full column about it on January 15, and then a follow-up post the next day to make sure his complaint registered. Through both pieces, curiously, there is nothing offered as to why the Swiss might be undoing Krugman’s fantasy. The subsequent post contains not one mention of motivation while all he had to say in the column about it was this:

And for three years it worked. But on Thursday the Swiss suddenly gave up. We don’t know exactly why; nobody I know believes the official explanation, that it’s a response to a weakening euro. But it seems likely that a fresh wave of safe-haven money was making the effort to keep the franc down too expensive.

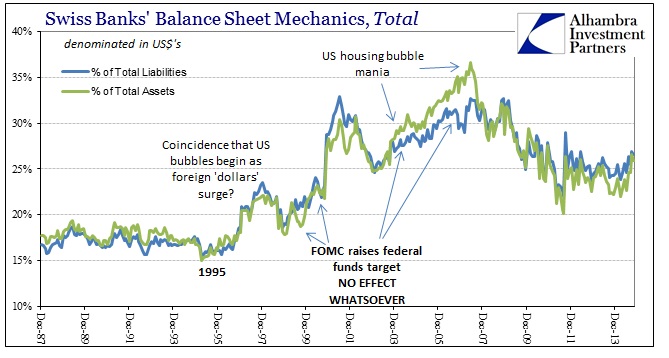

That isn’t even the full “official” explanation, as the SNB explicitly mentioned the “dollar.” That alone should have been enough of a clue, as the central bank in Switzerland was explicitly linking the end of the franc’s peg to the euro to a currency that should be, in Krugman’s world, unrelated to the chief monetary efforts. In other words, it more than suggests a financial complexity that goes beyond the central planning version of “let’s debase some currency.”

This is not to say that Krugman is unfamiliar with financial complications in carrying out these generic monetary instructions. His concern was not so much for the poor Swiss stuck in a world they didn’t quite relate to, but rather how surrendering on the franc would make the “deflationary vortex” that much harder to overcome everywhere else.

These days it’s fairly widely accepted that it’s very hard for central banks to get traction at the zero lower bound unless they can convince investors that there has been a regime change – that is, changing expectations about future policy is more important than what you do now. That’s what I was getting at way back in 1998, when I argued that the Bank of Japan needed to “credibly promise to be irresponsible,” something it has only managed recently.

For both the “saltwater” and “freshwater” combatants, the arena is with expectations (always rational expectations theory with these people). His mention of Japan 1998, however, is highly relevant to the QE problems that exist now; and in this case he is not wrong about what was then called “forward guidance.” That term has undergone a dramatic shift in the US under Yellen (aside: Bernanke’s recent blogs, in my mind, are directed more so at Janet Yellen undoing “his work”; see “secular stagnation”) but during Bernanke’s regime it was far more consistent with the Krugman version.

As he says above, a central bank at the zero lower bound has to “credibly promise to be irresponsible”, but that itself isn’t enough. Krugman in 1998 argued that they have to do that plus promise to be “irresponsible” for an undetermined period of time so that this “debasement” impulse would register in the minds of financial agents as the dominant setting for financial expectations. In other words, “market” participants must take the central bank seriously but also must not view the end to that effort as in sight. QE has to extend far over the time horizon or it will never get off the ground.

The reason for that is alarmingly simple, yet it never gets so much as a mention about policy complication (indeed, central bankers make it all sound as if all this were as easy as microwaving leftovers). Think about this in terms of a single bank. The central bank has just depressed interest rates, down as far as they can go on the short end, bringing with it the longer end. Nominal monetary theory says that is terrific for a bank because while returns are compressed at the longer end, funding costs are as well at the shorter end (as if banks only perform maturity transformations; another over-simplifying assumption). But, as has been pointed out repeatedly, it is not as symmetric as it sounds – in fact, the closer to zero at the short end the money markets get the less of cost reduction results in proportion to the depression on asset yields.

That discrepancy apparently takes place much sooner than any of the central planners appreciate, even though they were warned about it all the way back in June 2003.

I’ve been surprised to see the resistance among the bankers on my board to continuing reductions in interest rates. About the middle of 2002, we started getting resistance to further easing moves, primarily from our bankers. I was a little shocked at their inability, apparently, to lower their costs as fast as their income was going down.

To which Greenspan and his cohorts laughed it off, but any bank in that situation really has two choices: cut back on everything, including risk and limit operations to the most basic parts, or go full-blown insane and take every risk imaginable but use the cover of the Basel framework and an army of lawyers, accountants and Ivy League mathematicians to misdirect and hide it. Wall Street (as a euphemism for global banks in the eurodollar manner) clearly chose the second option especially 2002 onward. Post-crisis is much different.

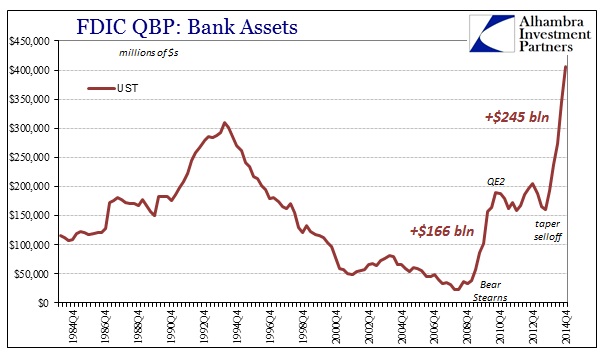

And that is Krugman’s central problem, as every Keynesian and monetarist are united in pursuit of trying to make Wall Street insane once more (beyond stocks which are economically useless). They want banks to lend and lend freely without regard to risks; they want more, more and much more credit flowing through every possible channel. But global banks have been, since 2007, taking instead that first option and staying in “risk-free” with a high degree of what Keynes himself once lamented as “liquidity preferences.”

The answer to that for the Krugmans of the world is for the central bank to be “credibly irresponsible” married to “forward guidance” that overcomes the “end of horizon” problem. As a bank, attuned to future expectations, there isn’t just the risk of participating in bubbles to think about (and the lessons learned from 2008), there is also the very big problem of QE actually being successful.

If you as a bank cast all those 2008 lessons about the dangers of bubbles aside and take the central bank at its QE-driven intentions, then you are going to be adding assets that pay next to nothing. That may not be as much a problem at the moment, as we can even assume that you have overcome the 2002 issue of cost structure, but if QE works as advertised in the real economy then at some point there will be an increase in short rates – your primary costs. Against that you have an asset structure that is highly inflexible as funding costs increase.

While you may be able to shield some market value declines of securities by shifting specific bonds and ABS/MBS to the “bank book” (held to maturity) and thus prevent any mark-to-market depressions, that does not apply to any loans made during the low-rate period and even then you are further locked into (once in the bank book assets must be held to maturity) that low-yield cash flow stream. In other words, like 2004-06, banks will be squeezed by the very success QE seeks to generate because they cannot possibly be flexible enough (just like wages and “inflation”) to match time periods.

That is what “forward guidance” seeks to overcome, namely to get banks past this “success” problem by assuring them it won’t be for a very long time – QE3 was promised to be “open ended” as the means of forward guidance to deter financial agents from thinking about it actually working. And so we enter the tangled mess of “rational expectations” where the central bank has to, essentially, assure market agents that its efforts will be so poor as to bear fruit only in a long-distant position. Should anyone be so surprised that banks are taking them at their word now? That is why every central banker on the planet uses consistently some variation of this phrase, “the economy is moving in the right direction but it has a long way to go.” Translation: we have to convince the economic side that it is working but also the financial side that it isn’t working “too” well.

In addition to that inconsistency of theory, central banks have further complications of the actual economy not really responding. Having been so burnt the last time, and most of the big houses only barely surviving (so many of the foreign ones having been “nationalized”) this idea of imbibing “forward guidance” is still foul as it relates to forgetting about all those consequences and just embracing all the bubbles. If central banks say QE isn’t all that effective, and now it apparently isn’t, there really should not be much surprise as to this kind of financial resistance. Banks have stayed in and around “cash” and the most safe and liquid instruments at the margins, eschewing much lending or huge risk appetites that QE’s proponents were so sure would result. There is no real reason for banks to take on real risk, as there nothing now to suggest good conditions for doing so, including central banks’ own demeanor, or even then in a true recovery; it’s as close to lose/lose as you can possibly get.

The difference between the US and Europe (and Japan for that matter) is the bond market. Monetarists here continue to suggest, even as they grow increasingly concerned about the building “slump”, that the US has had the better run since 2009 because of better policy; that is pure bunk. The difference here vs. Europe and Japan is the fact that the US has a massive bond market free of these banking restrictions on expectations whereas those other systems are much, much more overbanked. In other words, funding constraints and forward guidance problems don’t apply to about half the financial system in the US compared to only 10-20% of Japan and Europe.

In that way, the US was able to generate an artificial (and temporary) impulse of financial-driven activity that was free from these kinds of banking incongruities, to which monetarists are claiming directly as a means of “better policy.” Instead, it was that QE’s inherent contradictions applied to a smaller base – though that will not be much of a shield once it all starts to unwind, and the “better policy” will be a matter maybe much reversed.

To which Krugman yells into the winds of common sense that central banks still aren’t doing enough – though now they are taking him very seriously. To these brands of economists there isn’t enough that a central bank can do, as somewhere there is a magical formula which overcomes all these irreconcilable differences of logic and reason. Forward guidance is, in its perfect distillation, the intentional introduction of dis-logic and irrationality (and a high degree of pure foolishness) because general equilibrium theory says that both sides of the regression must (MUST) equalize.

As I noted yesterday and the day before, central banks, with Krugman’s qualified blessing, may now be possessed of going as far as possible to kill currency in order to see such absurdity carried out. Don’t just take my word for it; here is Dr. Krugman’s final thought on the Swiss matter:

So let’s learn from the Swiss. They’ve been careful; they’ve maintained sound money for generations. And now they’re paying the price.

In the bowels of academia, wrapped up in truly irreconcilable mathematics, that makes perfect sense. The one who acts most inchoately insidious apparently wins that race. These are the very same “experts” who cannot and will not understand where the recovery went.

Stay In Touch