Monetarism, at its core, is relatively quite simple. It would have to be, standing upon ground of nothing much more than generic concepts for almost every important economic factor. But all of it can be distilled into the idea of money supply; given “enough”, the economy will thrive. That view includes some of the worst of conditions so long as the monetary agent abides. The problem, then, is left to defining “enough.”

Heading into 2008, that was the state of orthodox economics and represented the chasm between the real economy, and the fear that was rising from it in terms of general public perceptions, and the profession class of economists. By and large, acknowledging a few that were outliers calling the buildup for what it really was, orthodox economists began 2008 quite confused. They understood, cursorily, the manifested violence on Wall Street but perplexed as to why the public might be thinking something truly depressing of the real economy.

Here is prominent economist Robert Samuelson at the end of March 2008, even after Bear Stearns:

Regarding the economy, it’s hard not to notice this stark contrast: The “real economy” of spending, production and jobs — though weakening — is hardly in a state of collapse; but much of today’s semi-hysterical commentary suggests that it is. Financial markets for stocks and bonds are described as being “in turmoil.” People talk about a recession as if it were the second coming of Genghis Khan. Some whisper the dreaded word “depression.” Meanwhile, Americans are expected to buy about 15 million vehicles in 2008; though down from 16.5 million in 2006, that’s still a lot.

And again in July 2008:

The paradoxical thing about today’s economy is its strength. No kidding. Consider all the hand grenades lobbed at it. Higher oil prices. The housing implosion. Large layoffs in affected industries: autos, airlines, construction, mortgage banking. The “credit squeeze” triggered by losses on “subprime” mortgages. Despite all that, the economy hasn’t collapsed. It’s merely weakened. Output in the first quarter of 2008 was actually 2.5 percent higher than a year earlier.

To be sure, there are parallels with the Great Depression. People fear what they don’t understand or expect. In the early 1930s, no one really knew why the economy had deteriorated so rapidly. Similarly, much of today’s bad news was generally unpredicted: the higher oil prices; the losses on subprime mortgages; the collateral damage to financial markets; the sharp run-up of food prices.

Why such confidence? Who was it that really didn’t understand? Fellow economist Greg Mankiw explains in a blog post he wrote also in March 2008:

It has become fashionable lately to see parallels between the current financial turmoil and what happened during the Great Depression…It has become fashionable lately to see parallels between the current financial turmoil and what happened during the Great Depression.

He then went on to quote, of course, his own textbook in seeing the bright light of economic salvation:

Yet most economists believe that the mistakes that led to the Great Depression are unlikely to be repeated. The Fed seems unlikely to allow the money supply to fall by one-fourth. Many economists believe that the deflation of the early 1930s was responsible for the depth and length of the Depression. And it seems likely that such a prolonged deflation was possible only in the presence of a falling money supply.

Indeed. There “could” be no worsening of the 2008 situation, financial or not, because the Fed had provided all the means to forestall the mistakes of its 1930’s ancestor. Its Chair was taken by the great economic scholar Ben Bernanke who made his name in studying exactly this point. If Milton Friedman first suggested and provided the first emphasis of the “money” story, it was certainly Bernanke that gave it the proper vigor and intemperance.

And that was the case even throughout 2007 and 2008, as the Fed “supplied” over and over “money” into the markets in more than just the standard reduction in federal funds. There were TAF and dollar swap auctions, too, in amounts that at the time seemed disproportionate for a reason – the Fed was trying to make a grand statement in that one regard if nothing else. The central bank would not repeat the 1930’s mistake of “money supply” leading directly to “deflation.”

Because of that economists were simultaneously enthused, about such “accommodation”, and confused, about why “Main Street” was so irrationally glum.

That even sparked a significant contrast with other monetary organs in other jurisdictions, chiefly the ECB. It is forgotten history now, but the ECB was raising its benchmark interest rate during the same period of high Federal Reserve accommodation. From August 2008:

The European Central Bank and the Federal Reserve are facing similar problems but pursuing different policies. The ECB has been raising interest rates while the Fed has been cutting them. The overnight federal funds rate is now 2 per cent while the corresponding ECB rate is 4.25 per cent. Which central bank is doing the right thing? Or could they both be?

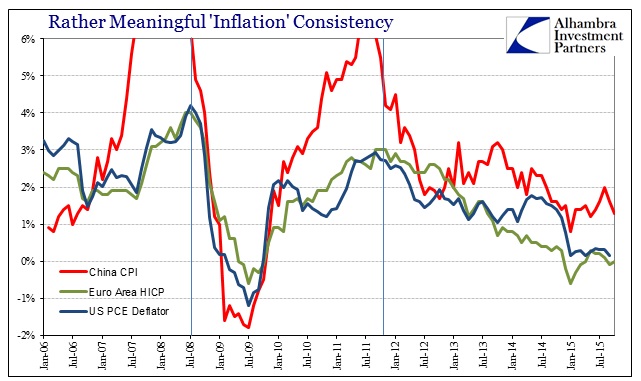

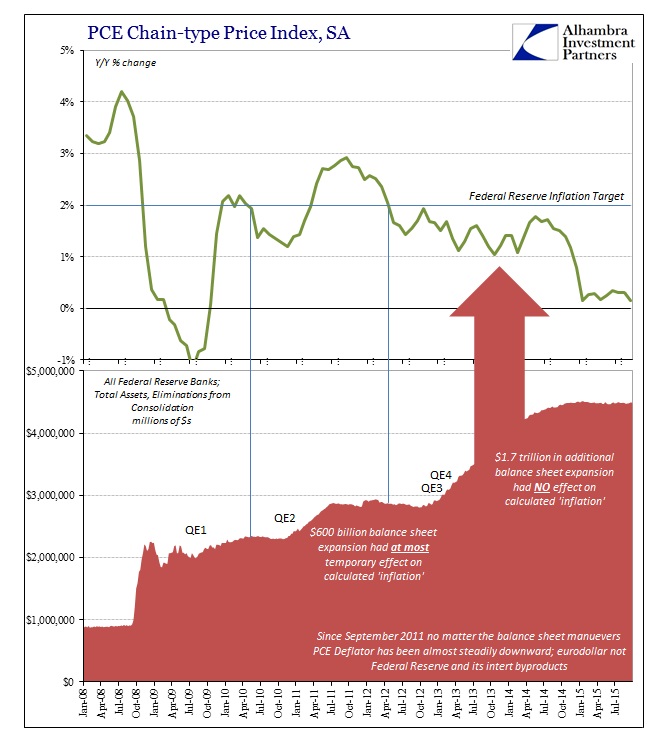

How about neither? It wasn’t ever considered, but this is an especially important and relevant point. The ECB and Fed departed upon fully separate courses but yet ended up in the same place anyway, as by 2009 there wasn’t a part of the globe in serious downturn. By even the count of the orthodox view of “deflation” (which isn’t really deflation, but that is another story), consumer price indices all over the world charged on that count; by July 2009, the US’ PCE Deflator, Europe’s HICP rate and even China’s CPI were all three negative. The imputations of “scaremongering” had faded by then as did the supreme confidence of economists (at least until it was safe to refocus completely to “saving” the system instead of adjudicating what had happened and why it was so wrong). All that occurred despite more and more “money supply” intrusions by the Fed and other central banks.

By the week after Lehman failed, the “money supply” figures had become truly staggering – and yet, it still didn’t prevent anything of the worst of the Great Recession. The fact that the economic event was and is referred to in that manner stands in sharp rebuke of the Fed’s money supply tactics no matter how large.

The Federal Reserve will pump an additional $630 billion into the global financial system, flooding banks with cash to alleviate the worst banking crisis since the Great Depression.

The Fed increased its existing currency swaps with foreign central banks by $330 billion to $620 billion to make more dollars available worldwide. The Term Auction Facility, the Fed’s emergency loan program, will expand by $300 billion to $450 billion. The European Central Bank, the Bank of England and the Bank of Japan are among the participating authorities.

At the time, those numbers were unthinkable in scale but still proved equally ineffective. By October 23, 2008, swap spreads had rapidly compressed to the point that the 30-year spread had for the first time turned negative and rejected a great deal of core orthodox theory. The markets would even dump again, as swap spreads were suggesting, in early 2009 as the economy globally bled extraordinarily in what sure felt like depression if only with SNAP lines instead of breadlines.

In other words, it’s as if the “money supply” contracted even though the Fed had offered what it believed far, far more than “enough.” At each stage of the crisis, however, such a position was continually refuted by the very fact that every “answer” was met with worse conflagration (not to mention, very importantly, that only banking “money” was involved as actual currency available for commerce was never at any time imperiled; the only panic was purely financial and debt, not money). In truth, the Fed had become detrimentally uninterested in modern money so that by August 2007 it stood ready to enact the ideas first written in 1963 to counteract financial seizure of the kind of 1930.

Milton Friedman even delivered a speech in 1960 that professed the same kind of ignorance only in the generation before him:

The profession of economics as a whole then shifted very radically from one course to another. From a general belief that the stock of money and the changes in it are tremendously important in controlling economic affairs, the profession shifted toward the view that money has little importance and does not matter except in rather trivial ways. It shifted toward the belief that the important things to look at are the flows of investment expenditures, on the one hand, and consumer expenditures, on the other. It was said that if these are taken into account, it really does not make much difference what happens to the stock of money.

And back again, as the “profession”, against its own infrequent but devastating admonitions, swung all the way back to monetary genericism. In this age, though, economics took great care about the “stock of money” only to set all considerations aside about the type, style or exact intermediation pathology of it. By thinking it had solved the great money supply issue, monetary economics devolved into nothing more than that single factor.

At the same time, of course, banks and banking underwent a radical shift, perhaps unlike anything ever seen in human history (as I would argue), to which central banks replied with a determined shrug. In the midst of great crisis, there was still no great effort to re-examine all that had been set aside in favor of generic money stock views. In the years since, nothing. Even in the small spaces where more wholesale consideration have penetrated (such as the minor disturbance a few years ago about shifting to a repo rate benchmark in monetary policy rather than the federal funds rate which “governs” a dead market) it has flamed out in favor of the confusing status quo.

That is the constant of this age, tracing back to August 2007; economists remain in a perpetual state of confusion particularly about how unsatisfactorily the economic affairs of the world have been conducted. That stands now in almost as great a chasm as early 2008, since 2015 has seen a dramatic shift in the ground for each side; “Main Street” again suffers this “phantom” downturn (it’s only a manufacturing recession, you see) while economists are full of the unemployment rate and a pending rate increase (even though it has, somehow, been delayed already by almost a year).

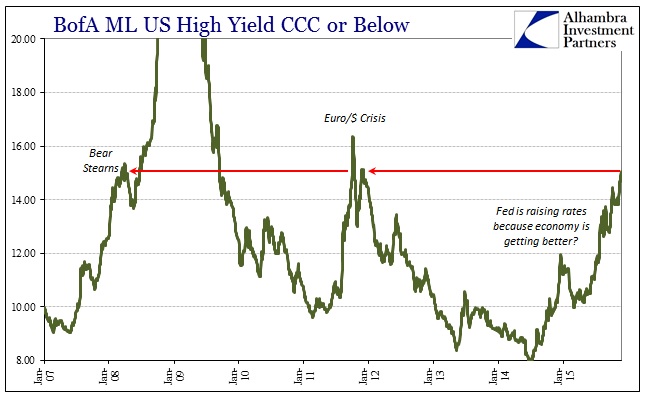

Such a contrast has been brought, as it should, to asset markets themselves. Writing for Invesco on August 11 (what timing), Scott Roberts, co-head of their High Yield Team, wrote:

We continue to be constructive on the high yield bond asset class despite the possibility of increasing interest rates. That’s because high yield bonds have historically performed well in rising rate environments. Why? Rates typically rise when the economy is expanding, signaling that companies tend to have increasing earnings and can better service their debt.

Their central point is as Yellen’s and Bernanke’s, namely that “money supply” has been taken care of and so the recovery will have to continue apace. All that was, or still is, missing is the factor of time which has lagged far enough, in the orthodox view, to finally put to rest all the negativity and lingering after-shocks of the Great Recession that wasn’t supposed to be. The simple equation of continued “flooding” of money supply plus time is unequivocal for the mainstream projection.

We appear to be doomed to history, as misreading the first time produces the repetition. It sure seems as if the global money supply of “dollars” is once more receding, as in places such as Brazil, China, Russia and even Switzerland have found themselves far more like 1931 than 2003. Of course, in minor turns, that fear has also extended to the US more and more over time this year; “transitory” no longer being spoken and written as forcefully or even much at all (except by people like me who point out the significance of it no longer being spoken and written much). If rising interest rates mean a healthy economy, and they do, and high yield performs very well in that circumstance, why is high yield on the verge of re-enacting 2011 if not early 2008?

The BofAML High Yield CCC or below Index rate is above 15% again (as of Friday), the same as it was not just in some of the worst days of 2011 but of equivalent to when Bear Stearns failed. In that respect, junk bonds are a prime indicator of actual, wholesale “money supply” which suggests not confusion about the downdraft in the global economy, US included, rather both explanation and projection.

In that regard, the issue of money supply continues to be quite simple even if the evolution of money has taken it beyond the absurd in operative condition and fact. In other words, the financial and economic system continues to conduct itself on ancient principles about money just with no longer any appreciation for what that might actually be. Interbank, global wholesale “dollars” are in full retreat meaning that the only open question is how much damage might be done this time.

Stay In Touch