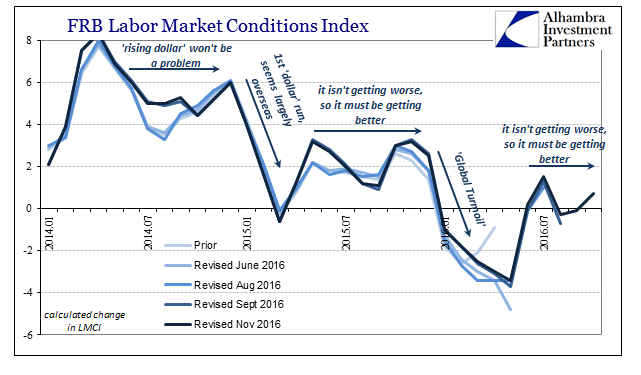

The LMCI was positive in October for the third time in the past five months. Revisions are to be expected in any statistic, but more so with the Fed’s factor model by its construction where it has to predict certain parts of its nineteen inputs. Not all those statistics are readily available when it is published and many undergo benchmark revisions themselves, so it is perhaps somewhat noisy if still at the same time exposing the idea of precision as more a fantasy than reality.

With those revisions in mind, as well as those that are surely to come, we are left with a labor market proxy that still very much fits our overall narrative. The economy is swinging from one “dollar” blow to the next. Right now happens to be one of those pauses which has allowed a measure of optimism to develop (so much that Alan Greenspan has been heavily booked again of late) but also some real economic “improvement” at least in that the “dollar” isn’t directly siphoning actual activity right at this moment (weak but not getting weaker). Monetary irregularity is a real problem, not just theoretical. During the huge, global liquidations in January and February, as last August, we will never know how much activity was withheld or foregone because of inflexible or difficult finance, but there can be no doubt that there was some and that it was significant.

The problem is that once the “dollar” pressure is removed that discontinued activity is either lost or permanently altered; only part (at the margins) is delayed. Again, this makes sense on a personal or individual actor level as conceived of in real economic functions as risk. You intend to do something in January only to find yourself on the hook for being unable to fund that thing, so when conditions do somewhat improve you may have reconsidered whether it was worth the effort in the first place.

It is this process that we find all over the place; in various accounts and in various jurisdictions. The LMCI is just another one. Despite all the revisions, the “dollar’s” influence remains as prominent as ever.

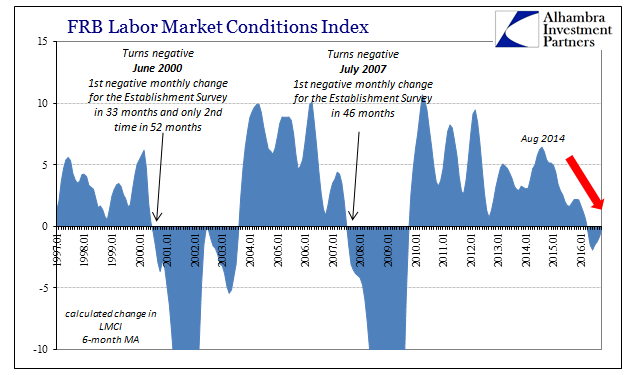

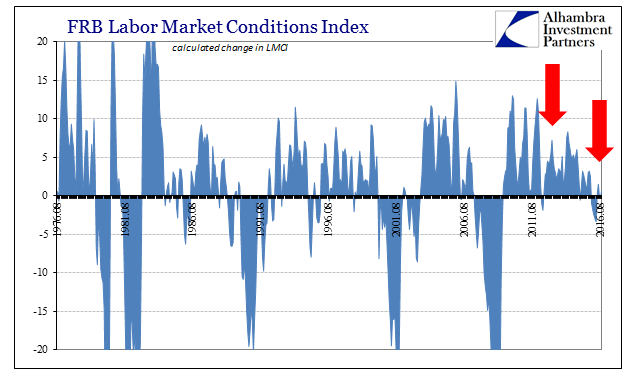

The two prior “dollar” waves are unmistakable, as are the spaces in between – the past few months counting as the latest of those latter. What we can’t accurately analyze (forget measure) is just how much damage the economy has already absorbed in those two “dollar” episodes. All these statistics like the LMCI suggest is that it is more than reasonable to believe that there has been significant impairment, even if we can’t immediately tell by how much. As I wrote Friday with regard to the payroll stats, the “quantity” doesn’t really matter as it is this pattern that tells us everything important:

What we know with some solid assurance from this data is that the economy in 2016 is appreciably weaker than it was even in 2015, and that this has occurred in an overall economy that still hasn’t recovered from the Great “Recession.” As the IMF declared through its modeled revisions, from that we can claim that the recovery didn’t come and further expect that it never will. That’s what this unemployment rate, as well as the slowdown in the headline payroll figures, actually means.

In other words, there can be no doubt that the economy really did slow starting in 2015 and despite all claims to the contrary it wasn’t a temporary misstep. The fact that it did slow so much as to be picked up in employment figures of all types is what is relevant, especially since the economy had never recovered from the Great “Recession.” That the LMCI, as other statistics, follows very closely the “dollar’s” input simply shows cause with effect. The economy isn’t actually getting better, it is for now just not getting worse.

Stay In Touch