The recession of 1980 stands out in US economic history. It was by several measures a severe contraction, yet it only lasted a very short while. Contemporarily, it was believed to have been limited to just parts of two quarters. The current estimates describe it as a total of seven months from January to July 1980.

That stands in sharp contrast to both the recession preceding it (1973-75) as well as the one that immediately followed (1981-82). Both of those are considered in the popular imagination more traumatizing. In comparison to the 1973-75 event, the recession in 1980 was outwardly entirely similar – right down to a repeat of oil crisis and inflationary circumstances. Again, the difference was not depth but length.

To explain the discrepancy, Princeton economist Alan Blinder in 1981 wrote a paper, published by the Brookings Institution, that noticed what is today a common element of economic analysis. In his time, however, economists had for a long time before ignored a crucial sector of marginal economic changes. This part of GDP, or GNP as was in use then, was incredibly small which is why it was for a long time practically ignored. As Blinder wrote:

Relative to its importance in business fluctuations, inventory investment must be the most underresearched aspect of macroeconomic activity. A hot topic in the 1950s, research on inventory behavior apparently went out of style in the early 1960s and languished during the 1970s. But there was never any good reason for work on inventories to fall out of fashion. The importance of inventory movements in business cycles did not end in the early 1960s.

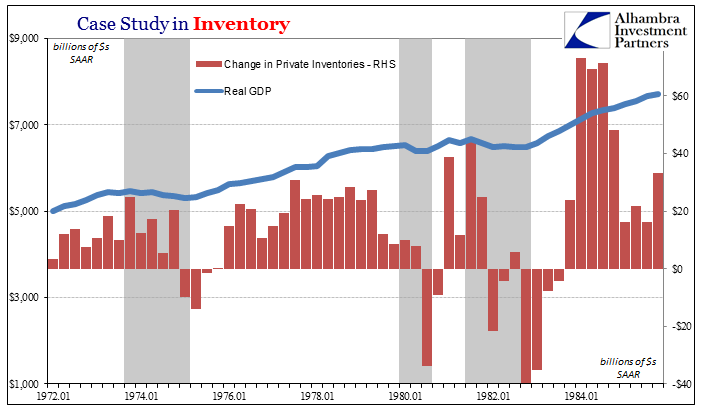

Indeed, if there was a major difference between 1980 and 1973-75 it was, as Blinder described, calculated, and at great length regressed, the timing of the inventory liquidation. It is this latter process that usually triggers, or at least signals, the recovery. Almost like a stock market correction or crash, capitulation among businesses is a healthy part of moving forward.

In terms of GDP, the changes in inventory do seem like a trivial matter. Yet, in 1973-75, the recession was long and drawn out, with that final inventory capitulation not arriving until five quarters in. The same, mostly, repeated in the 1981-82 recession, with an even more dramatic liquidation right at its official end.

The 1980 recession, by contrast, was met with liquidation very quickly and was a very sharp one at that. Once that happened, contraction ceased and immediately the economy began to recover.

This is not to say that inventory is the only factor in recession or recovery, nor is it in the scope of this article to propose reasons for the differences in especially manufacturing behavior in 1980. The purpose is instead to refresh our appreciation for the important role that inventory plays as a cyclical factor.

If we are interested in investigating a potential path for the US economy, and by extension the global one, in 2017 it has to start with inventory. Already this year has disappointed in many ways and across many accounts. What was supposed to be, for many, a renewed economic trend worthy of “rate hikes” and the claims about conditions that would accompany them has been left with too much of the same weakness.

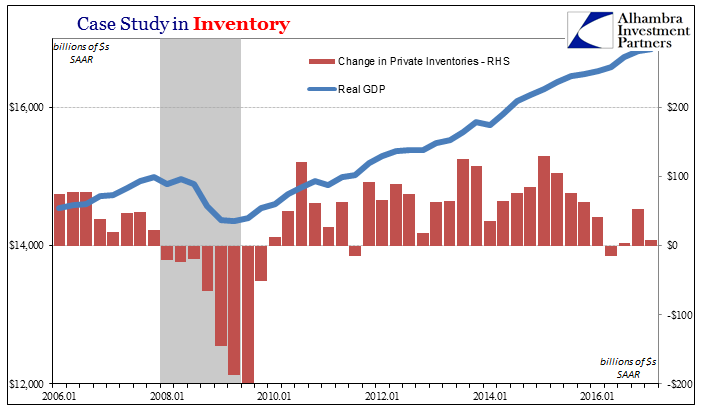

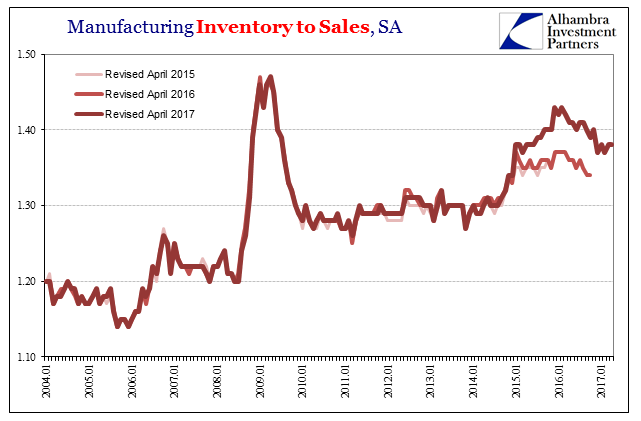

Though the downturn in 2015-16 was not a recession, at least not officially, it was a significant and significantly severe event so as to invoke cyclical processes. Inventory was a clear part of what became a two-year long manufacturing recession, shallow though as it may have been. But according to GDP figures, the inventory response at its end was far short of liquidation.

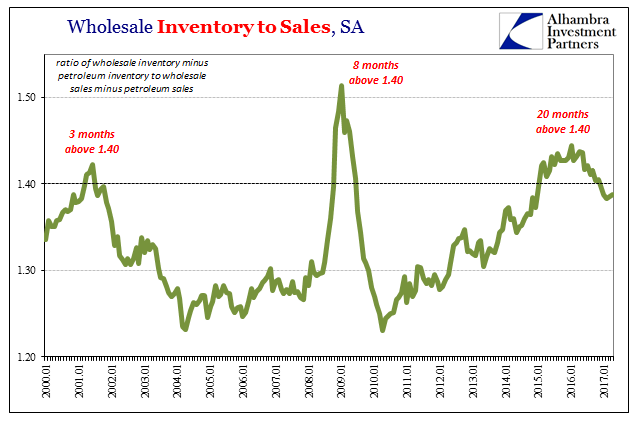

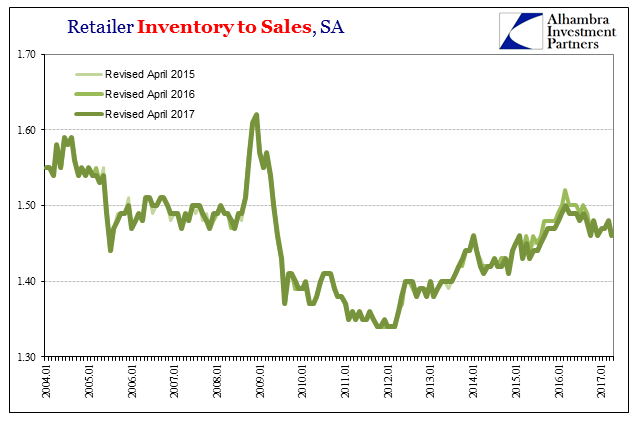

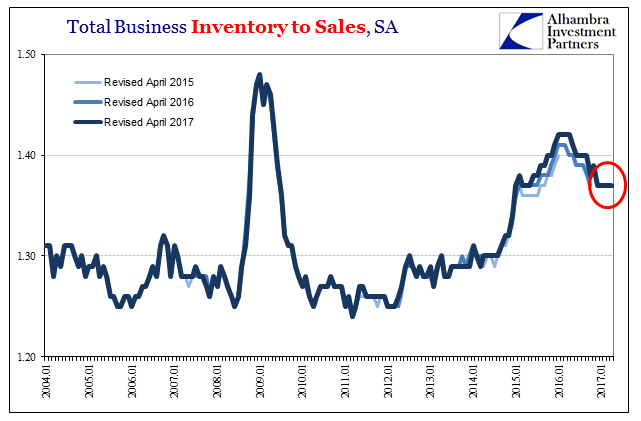

That calculation and the interpretation that goes with it is matched by data found across several series. The Census Bureau’s various accounts of inventory-to-sales, for example, clearly suggests first the downturn and then only a small, partial adjustment to it. At the wholesale level, excluding petroleum, inventories remain as high as they were during the dot-com recession, not normalizing even slightly to conditions and levels that existed in 2014 before the slump fully manifested.

In Alan Blinder’s analysis, it was retail inventories that mattered most, but in a rebuttal published also in the same Brookings collection authored by Larry Summers, the case for retail inventory isn’t as convincing as it is for the whole supply chain.

Blinder makes an overwhelming case for inventory investment as an important component of business cycle fluctuations. However, he is much less persuasive about the importance of retail inventories. The disaggregation of manufacturing inventories into three components ensures that much of their variation will be relegated to the “all other covariance terms” category…Finished goods are stored between the time they are finished and the time they are consumed. It is of relatively little economic significance whether the appliance that will someday be mine today sits in a wholesaler’s warehouse or a retail store’s showroom.

I think most people today would agree with Summers’ assessment, and thus the crux of the current economic condition. It’s not that retailers have persisted with low levels of inventory this year, it’s that it is more so a very clear imbalance of wholesalers as well as manufacturers (manufacturing inventories include goods in all stages of production, from raw material to finished goods, though much less of the latter), and therefore an aggregate, economy-wide issue.

It has left the whole of the domestic supply chain, which incorporates imported products especially in the wholesale channel, extremely bloated both as a comparison to the post-Great “Recession” period as well as the business cycle preceding it. This year so far, little progress has been made so that renewed restocking might reignite continued lagging production.

Many economists and those in the media who listen to them (or are forced to by rigid editorial standards placing total emphasis on only credentials) have contended that none of this really matters because ours is a service-oriented economy. It was common throughout 2015 to see stories written, or speeches given, laced with the idea of 12% manufacturing. In other words, they wished to dismiss clear weakness in the production of goods as only that small portion of GDP and therefore in their view it really didn’t matter all that much.

These same economists and their media, however, were the same people who have been forced to clarify the circumstances of that period to finally admit there was a substantial if to them “unexpected” economic slump, and to some very serious degree. Rather than having been a mystery, perhaps manufacturing wasn’t then, and isn’t now, so unimportant especially when it comes to setting the overall, marginal economic trajectory. After all, a huge portion of the so-called service economy is nothing more than the selling and transport of goods.

The usual symmetry of cyclical circumstances, which apply to near-recessions as well as full ones, dictated that in 2017 there should have been a familiar and inarguable acceleration. There hasn’t as yet and increasingly it appears there won’t be. If that is ultimately our situation, and the data is uniformly describing it this way, the stubbornly high levels of remaining inventory are very likely one of the primary factors, if not the primary factor, in holding the world economic system in its weakened, almost perpetual near recession-like state.

Stay In Touch