One of Candidate Trump’s biggest priorities was to renegotiate NAFTA. Seen as an accelerator for harm not just inside of the nation’s rust belt, the incoming administration made it a top priority. Blaming the trade deal for the loss of 700k manufacturing jobs, Robert Lighthizer, the US’s top trade official for the renegotiation process, said in August as talks got underway, “For countless Americans, this agreement has failed.”

Canada and Mexico, of course, don’t quite see it that way. Officials from those two countries struck a very positive tone in sharp contrast. They signaled a readiness to redo the treaty, but only insofar as it might be “modernized.”

Despite what looks to be contentious bargaining, the conference was put on an accelerated schedule. Round 1 started in August and was to take on one of the most crucial, and combative, parts – rules of origin. In all, there was expected to be seven rounds to the process, all completed by December, early 2018 at the latest.

The condensed nature of the renegotiation is actually being pressed by the Mexican delegation. Current President Enrique Peña Nieto is prevented from seeking a third term, making next year’s election an overriding concern. Economy Secretary Ildefonso Guajardo, that country’s lead representative, repeatedly warned throughout early 2017 that no new NAFTA agreement would be possible during the 2018 election campaign.

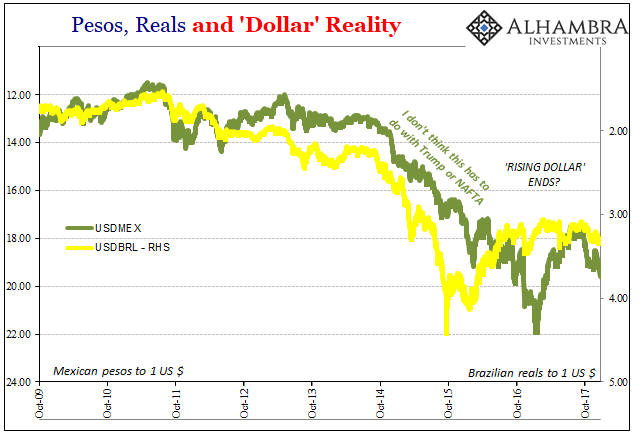

There seems to be a lazy shorthand emerging with regard to these talks anyway, and the implications for their outcome. In other words, the mainstream assessment appears to see them as a negative especially for Mexico. Whether or not that’s true doesn’t really matter; what does is that whenever the Mexican peso falls against the dollar it is immediately blamed on whichever round of renegotiations happens to be most recent.

When the peso was pounded throughout October, for example, that was surely because of Round 4.

After rallying for much of 2017, the peso has tumbled more than 7 per cent against the dollar over the past month, making it the worst-performing emerging market currency over the period.

The fourth of seven rounds of talks on renegotiating Nafta, a landmark free-trade deal between the US, Mexico and Canada that came into effect in 1994, has been particularly harsh on the peso in recent days.

Its initial start lower was blamed on the third group of talks then taking place in Ottawa. It would seem somewhat irrational to suggest a new potential NAFTA was the cause of the peso’s problems at that point, particularly since Round 3 ended in a high degree of acrimony and ultimately pushed later rounds into 2018. Round 4 was no better.

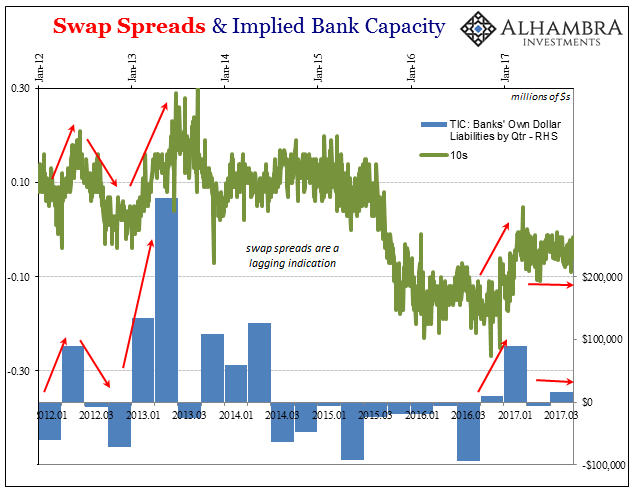

This is the type of groping for narrative that has become commonplace in an age where certain kinds of possibilities are removed from mainstream consideration. In the repo market, for example, a sudden surge of repo fails for many can only be due to a huge parcel of UST shorts betting on the recovery narrative, to the explicit preclusion of all other possibilities. It doesn’t matter that in the past Treasury yields (particularly the long end) are generally lower for them, or that repo fails typically group with other indications suggesting instead troubling liquidity issues, we are told constantly that those things cannot happen so far past the events of 2008 especially given all the global money printing.

Yet, there are connections to be made, “dollar” problems so clear that it reveals instead the naked agenda of those unwilling to talk about them. Preferring NAFTA (or still the now faded whispers of 2a7) is an indication of at best laziness.

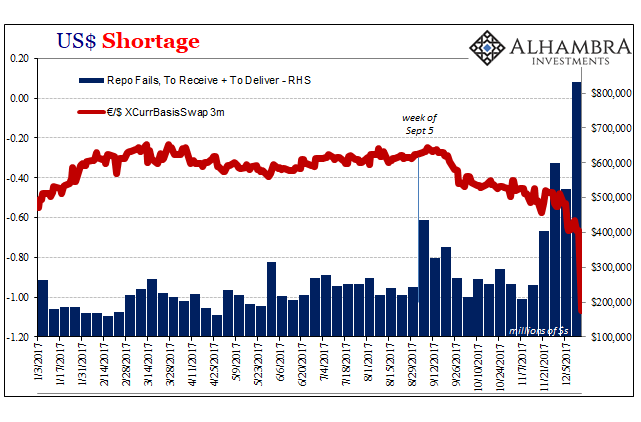

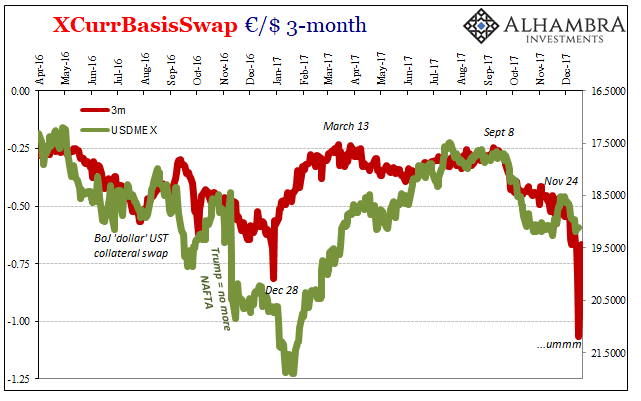

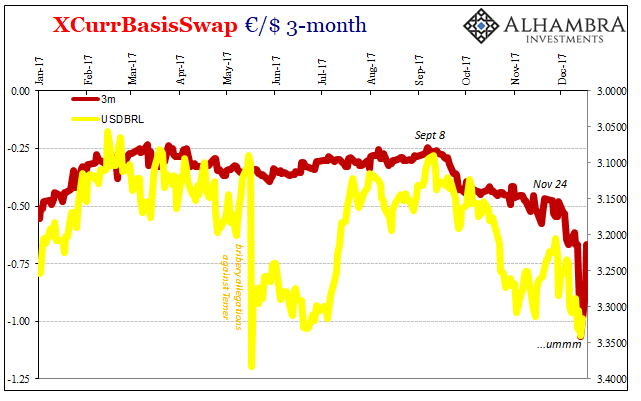

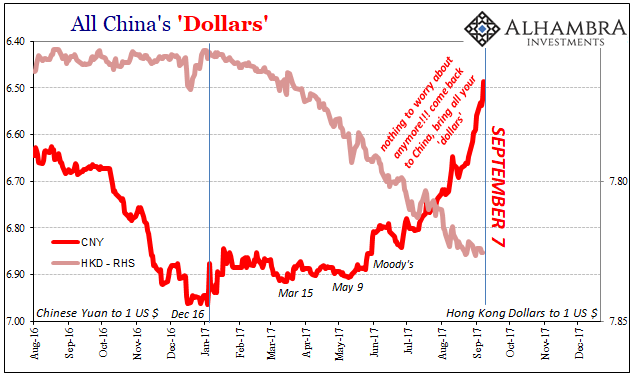

Repo fails had spiked the week of September 5, only to be outdone by those in the last week of November. Between those two weeks, global FX basis was dragged drastically lower – until the middle week of December when especially dollar-euro cross currency swaps fell off a cliff reminiscent of 2011.

Unsurprisingly, the FRBNY reported last week that during the crash in the basis, repo fails jumped again – this time to more than $800 billion! The proportionality of that last week is key here, leaving nothing to the “nothing to see here” lack of critical thinking. Repo fails, like the negative basis, are monetary issues of negative supply and troubled redistribution; all related to balance sheet capacity.

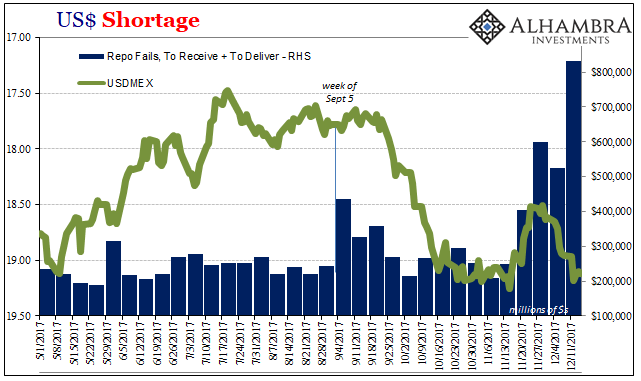

That was nearly twice as much as recorded back in September when all this weird (for the mainstream) stuff began. The connection between cross currency (negative) basis and repo fails is an easy one to make; and so is the Mexican peso.

If we look upon currencies in the modern eurodollar way, their movements tell us about eurodollar conditions rather than things like interest rate differentials (expected and real), local monetary policy, or economic considerations including trade agreements. A falling peso might indicate instead localization of a larger “dollar” and still unsolved issue.

It starts to look less and less like NAFTA and more and more like “dollar.” All throughout the first seven months of 2017, the peso had erased a lot of its losses from the previous year despite what everyone knew was coming later in 2017 with regard to trade renegotiation. Yet, it didn’t fall apart after Round 1 or 2, but the week after the fireworks in repo and coincident to a clear change in the basis regime.

The peso is still falling this week even though Banxico, Mexico’s central bank, undertook some $500mm in two foreign currency hedges to staunch the drop. They didn’t work, as the exchange rate fell to nearly 20 again for the first time since March.

Mexico, however, is not alone in its currency plight. If it was, the “blame NAFTA” excuse might be seen with some minor plausibility. But a whole lot shifted in early September, and then again in the middle of November.

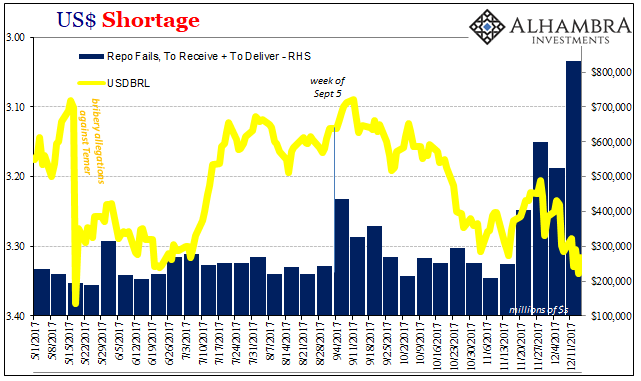

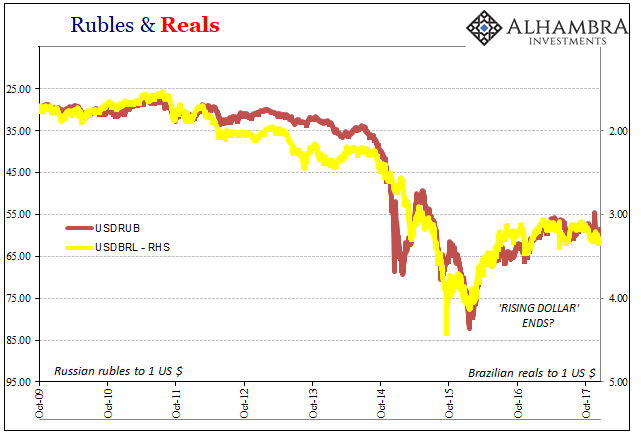

Like Mexico’s peso, Brazil’s real had enjoyed a serious rebound from its “rising dollar” lows set during the “global turmoil” of that prior period. Apart from a massive selloff in mid-May over allegations the new Temer government was also like the previous Rousseff administration engaged in bribery, the real had at least stabilized around and even above 3.15 for much of this year.

That all changed in September, when the spike in repo fails and the changing basis pushed the currency below 3.30 again, back to lows where it was on that dramatic day when the (alleged) corruption news shook Brazil so very deeply.

To put them in perspective, these moves in either currency are small in comparison to those of 2014-16. That doesn’t make them any less noteworthy, though. For one, neither the peso nor the real (nor the ruble, for that matter) have come anywhere near retracing their prior collapses (and those were not singular events, either, but clusters of selloffs all bred by the same kinds of global “dollar” conditions). “Reflation” in the second half of 2016 was a real trend, but noticeably limited almost everywhere including these monetary pieces.

What happens if that idea, reflation, picked up in some indications of balance sheet capacity is now long over? There was already a good deal of evidence that this was the case long before the events of September.

It might propose, then, if not a full-throated resurrection of the “rising dollar” (and we shouldn’t expect one) then at least the very fertile conditions for that to begin happening (again, it’s a process not a single event) all over. It would not necessarily work out in the same way, nothing ever truly repeats, after all we are still working through responses to the last one.

Which brings us to:

Stay In Touch