The lack of issuance and supply over the last almost year or so, that’s what makes the TIC data so fascinating. And relevant, if for other reasons, too. CLO issuance, according to a bunch of sources, peaked back last June. Remember that whole “recession scare” with the yield curve last summer? It wasn’t just a scare, at least not in this one key segment of corporate credit.

In a way, it therefore perfectly describes the bigger picture since mid-2019. Serious concerns last year paving the way for an incredible shock this year. In terms of the economy, we are still trying to assess the damage. Corporate credit slamming completely shut is one huge reason why.

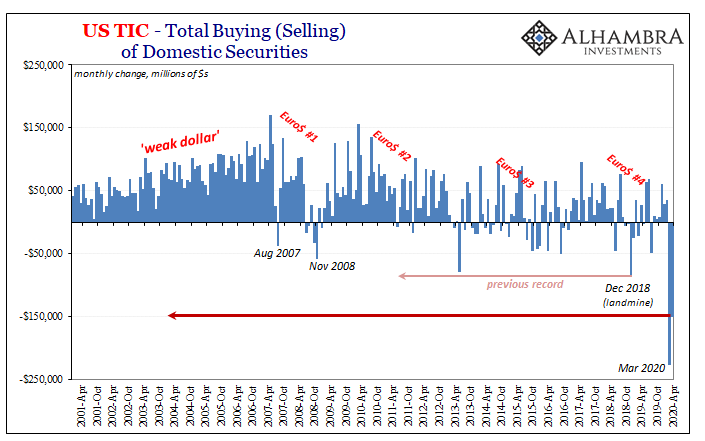

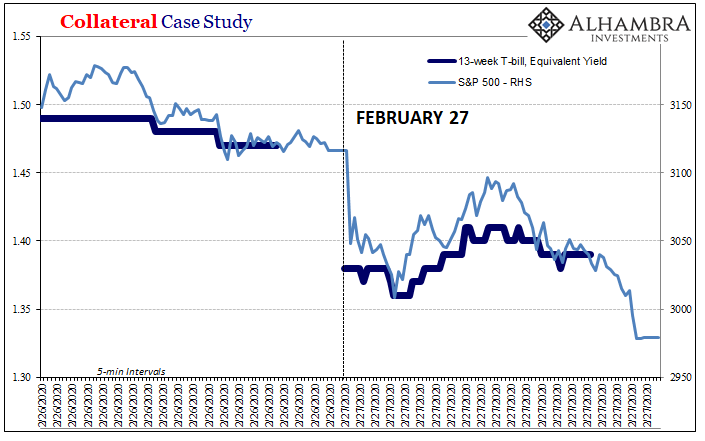

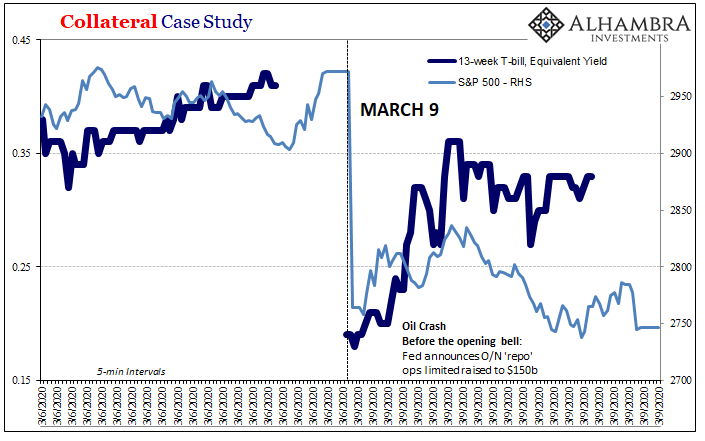

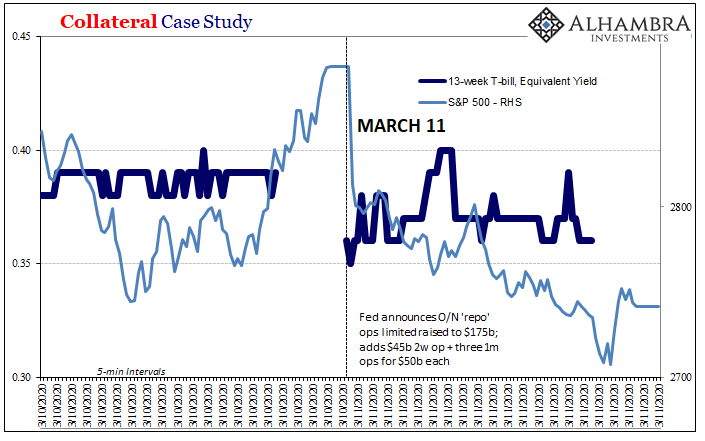

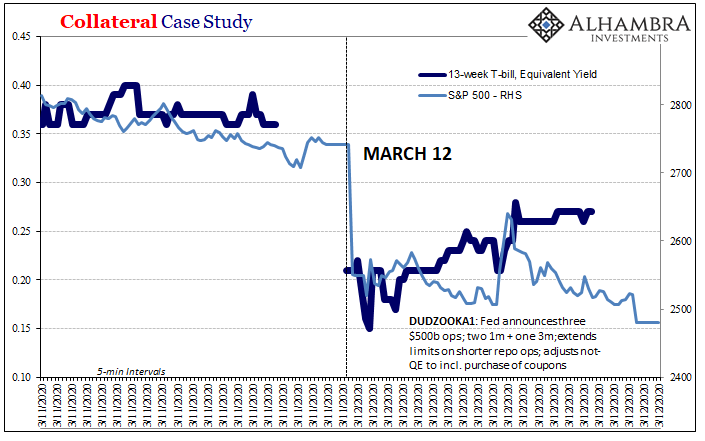

GFC2 was as well perfectly defined by what went on here. Repo and the bottleneck.

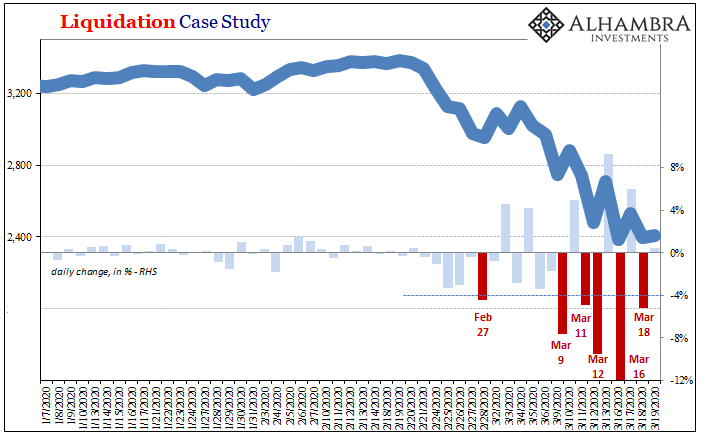

What that had meant for CLO issuance in March was plainly obvious. Jay Powell today says “we saw it coming” even though there’s only evidence the FOMC was caught totally by surprise, completely off-guard by this:

With an overflow of grim metrics in the secondary loan market, the window for new issues slammed shut in March, which produced no new institutional loan volume, the first time that has happened in a month since December 2008. Moreover, $14.4 billion of loans were pulled or postponed last month. As a result, only three loans allocated in March, all February launches. [emphasis added]

In short, there was no market for risky corporates – not just CLO’s, but all other forms, as well. So, if Jay saw it coming then why wasn’t he prepared to play his puppet show in corporates until May? The question answers itself (in more ways than one).

The lack of a market wasn’t limited to March, either, as issuance was dry as a desert in April, too. And that’s odd, in a good way, for our purposes, since CLO’s appeared as if by magic at least in TIC figures for both March and April. What I mean is, these couldn’t have been new issues, therefore where did these things come from? Why? Why then?

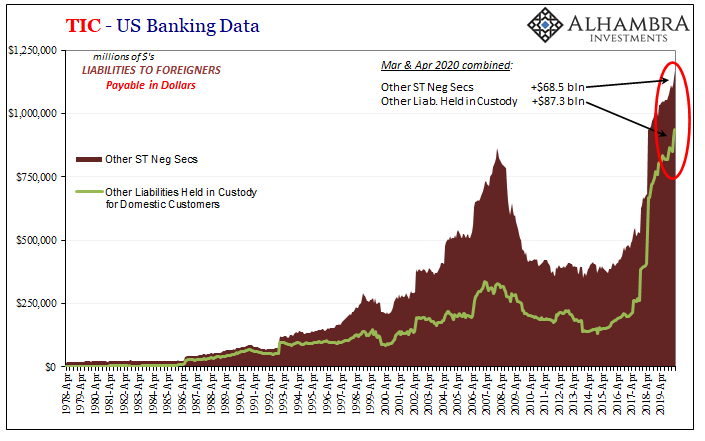

The specific TIC numbers, like everything else about these two particular months, were unusually large: Other Liabilities Held in Custody for Domestic Customers (by US banks liable to foreign counterparties) increased by $87 billion combined in March and April 2020 (green line below). That was, by far, the largest such gain in nearly two years. You have to go all the way back to June 2018 (the month after May 29) for something close (and the Treasury Department says that was due to a dislocation, improved reporting in the space or something).

OK, so let’s back up a minute. For the two years since May 2018 when I claim the events on May 29 first introduced the possibility of the bottleneck, CLO’s have been showing up in these cross-border custody figures for reasons not stated (or stated well enough). Furthermore, they continue to show up, in custody, even during the latter months when issuance at least domestically has been way down and in the last two months less than zero.

I wrote last July to where and how to begin literally translating this data:

For whatever reason(s), there’s been a truly massive increase in US bank liabilities in the form of other securities (CLO’s) belonging to non-bank foreign agents. At the very same time, for whatever reason(s), there’s been a slightly larger increase in US bank liabilities being held in custody for domestic customers.

And much if not most of whatever’s going on is being run through the Cayman Islands.

We aren’t left with too many options to consider. One would be US-based hedge and/or mutual funds bulking up on the assets of wealthy tax shelterers speculating wildly about perhaps EM corporate junk (CLO’s in dollars), buying up each and every syndicated tranche they can find and using specific Cayman Island subs for domestic US banks as their agent acting on their behalf (custody, too).

Since that would amount to a massive “capital flow” into the rest of the world, a generally very positive thing for the rest of the word, particularly EM’s, it doesn’t fit the situation one would honestly describe around the globe beginning around, say, December 2017.

If instead we start to think about all those “others”, other intriguing possibilities do line up. Custody. CLO’s. Caymans. Domestic and foreign nonbanks.

Shadow repo transformation? A gigantic collateral call?

Not that we needed it, but more good evidence for that likelihood – which is now nearly certain. The CLO’s which show up in TIC custody owned offshore via the Caymans cannot be newly manufactured securitized pools; they are almost certainly, in my view, 2016-18 vintage which had previously worked their way otherwise unseen (shadow money, after all) into collateral chains that since May 2018 have been increasingly unwilling to take them at prior values.

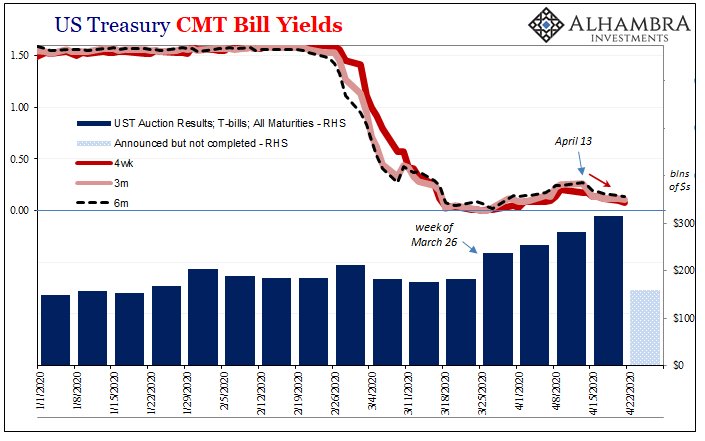

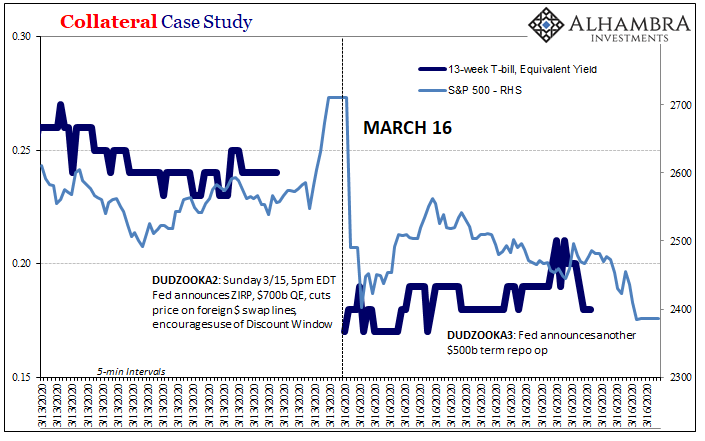

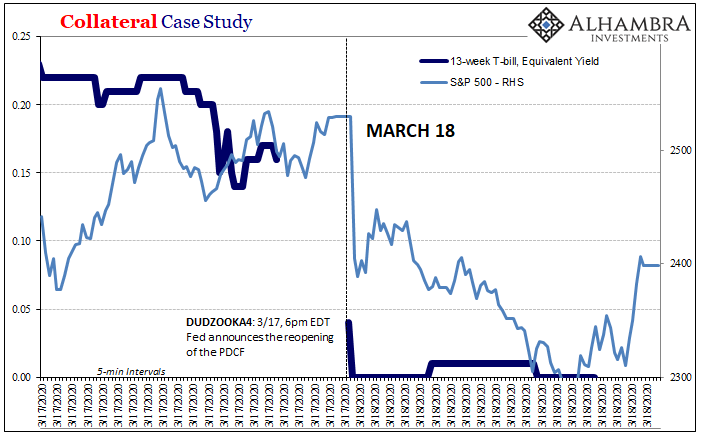

Haircuts adjusted, at some times, like March or April, very harshly requiring either an unwinding to all the related repo transactions behind them (including securities lending and transformation), which meant fire-sale liquidations, plenty of those on record; or, a desperate scramble for alternate pristine collateral (T-bills) in order to try and stay afloat a little while longer.

As in most cases, we clearly observed an overwhelming trend for both and not just in March. T-bill demand remained very high in April, too.

Until Jay Powell’s magic words could gift them a temporary (yes, temporary) reprieve.

How did these things get into the repo system in the first place? Globally synchronized growth. Not actual recovery, mind you, as the term implies, rather the idiotic attempt by central bankers to (prematurely) declare victory over the Great “Recession” and its suspiciously lengthy aftermath which by nature of its time component had thrust those same central bankers under suspicion and had kept them there for years.

What that had meant in technical terms:

Starting in 2016, however, things collateral-wise began to pick up for the first time. According to updated estimates from Manmohan Singh, the total volume of pledged collateral grew modestly from $5.8 trillion in 2015 to $6.1 trillion. But with the 2017 introduction of the slogan “globally synchronized growth” and consistent official emphasis on it, the aggregate exploded to $7.5 trillion – an increase of 23% for this money market that hadn’t really seen any kind of growth in nearly a decade.

Of that two-year change, sources of collateral had jumped by $600 billion meaning the velocity also ticked up (to 2.0 from 1.9) accounting for most of that $1.7 trillion rise.

Dealers were back to repledging again! Maybe not in the way they had been before 2008, but certainly over and above the seven years following the crisis.

More importantly, I believe, the sourcing of collateral. The vast majority of it came from the “securities lending” side of things, $400 billion more in 2016 and 2017 compared to $200 billion due to hedge funds.

Why did so much of this “visible” (which only means estimates pulled from bank report footnotes; who really knows how much more hidden in the shadows) collateral show up from the securities lending businesses? What was really behind the apparent need to transform so much collateral (thereby setting the system up for the bottleneck I’ve been warning about since at least the middle of 2018)?

Junk, man.

Central bankers aren’t merely incompetent, they are, and have been, actively harmful. Not only did they openly encourage risk-taking without anything to back up their forecasts (there was no evidence for an inflationary acceleration in the US let alone globally), even after what had really happened during GFC1 (repo collateral, not subprime mortgages) officials still take no account of this side of what is the ultimate backbone keeping the world’s reserve currency system in motion (or not).

It’s not merely a minor blind spot, it’s an inadvertent acknowledgement of the thoroughness of this official corruption.

And these are just rough estimates. Despite an increasingly compelling and widening academic investigation about the importance repo and more so repo collateral, these remain outside of the mainstream. Certainly outside of most if not all monetary policy considerations. Collateral still, to this day, does not factor for people like Jay Powell.

I wrote that last December. For Mr. We Saw It Coming, Powell sure didn’t see it coming. He doesn’t even know what “it” is, let alone where to begin looking for “it.”

Fire them. Fire them all while we still can. The bottleneck ain’t done, the same fault-lines still underneath, it had only revealed itself in a big way (by crushing every market) for the first time in March.

Stay In Touch