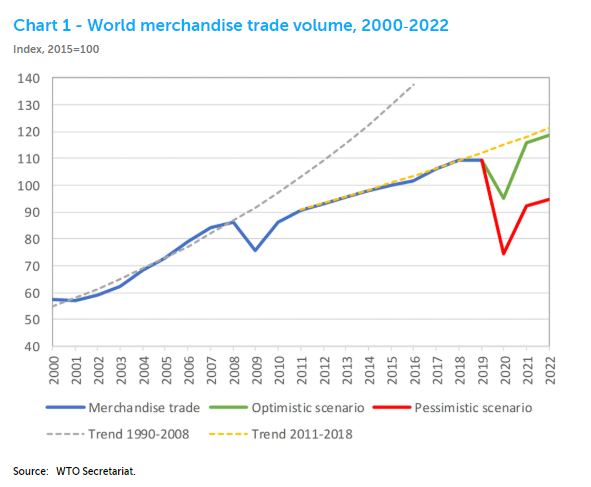

The good news: the World Trade Organization (WTO) has crunched the numbers for 2020’s horrific second quarter and where global trade is concerned it may not have been as bad as first feared. Make no mistake, it was bad but not crashing down as far as the most pessimistic of the dreamed-up scenarios.

Given where things stand now with only partial data and related soft figures to go on, the organization believes trade volumes across the global economy suffered a 14% reduction in Q2 from Q1. It had been thought the worst might get down past -15%; which in terms of trade volumes would have been nightmarish.

Where the good news ends, though, is where the most important parts come in. While it might seem reasonable that if the trough isn’t as bad as feared then the rebound should be better; so far that isn’t looking to be the case. On the contrary, for this higher low the initial indications are, well, more like lower highs.

However, as WTO economists warned in June, the heavy economic toll of the COVID-19 pandemic suggests that the projections for a strong, V-shaped trade rebound in 2021 may prove overly optimistic. As uncertainty remains elevated, in terms of economic and trade policy as well as how the medical crisis will evolve, an L-shaped recovery is a real prospect. This would leave global trade well below its pre-pandemic trajectory.

Let’s not forget: their “V” wasn’t actually much of one to begin with.

As I’ve written from the very beginning, the real nightmare was never going to be Q2 2020 – it was what kind of recovery might follow from it. Time is the major component in all things. More and more the dreams of the “V” recovery are being overtaken by sluggishness on this “good” side of however bad.

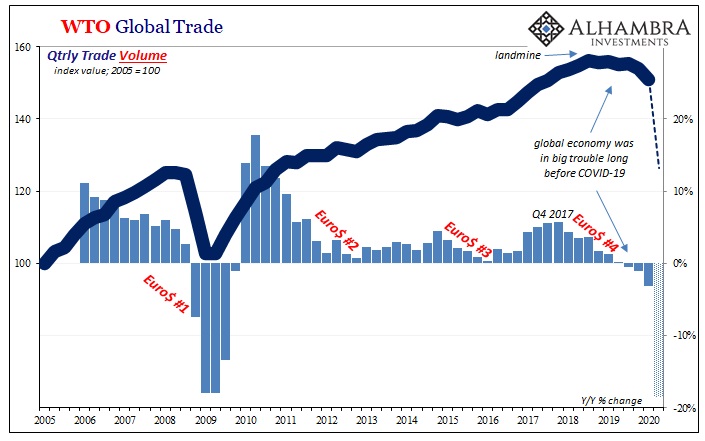

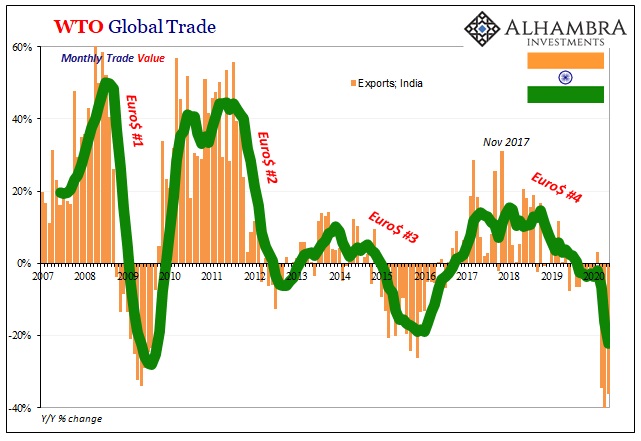

A big reason why, I believe, is what you see above in how the global economy was behaving long, long before we got to COVID. Throughout what had been an atrocious “recovery” from GFC1 and its Great “Recession”, both words fully deserving their quotation marks, still trade volumes hadn’t once declined on a year-over-year basis.

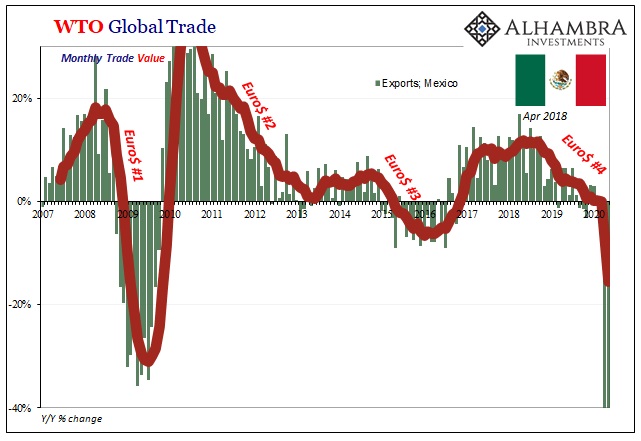

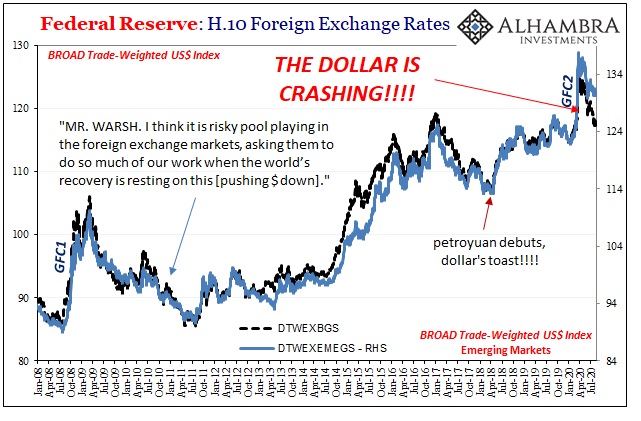

But Euro$ #4, the nastier of the subsequent three, had changed all that. While Economists kept blaming “trade wars” (remember those?) economic data instead fit seamlessly in the monetary/liquidity picture painted carefully and in painstaking detail by bond markets (and even stocks, to an extent).

The world was already in big trouble as 2019 came to a close. The WTO even manages to admit that much:

Global trade growth has been slowing since the fourth quarter of 2018, finally turning negative in 2019Q3. The seasonally-adjusted volume of world merchandise trade was already down 3.0% year-on-year in the first quarter of 2020, a decline that only partly reflects the effect of the COVID-19 pandemic. [emphasis added]

Truly strong economies rather than those which are modeled to be that way can weather the worst storms far better. Weak economies, by contrast, when they get hit with a serious dislocation, they aren’t going to going to be able to come back from it so easily. And it won’t matter how many sold out puppet shows are run by central banks.

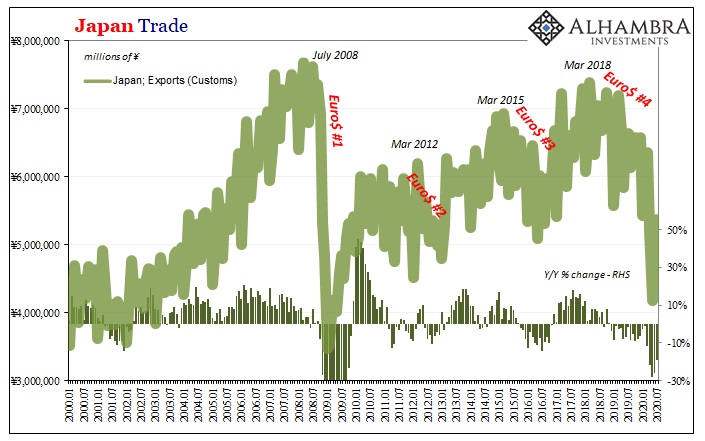

Of the hard trade data we do have coming in for the months of June and July, it’s not good. Japan’s Customs Bureau, for example, reported on Tuesday that for the month of July 2020 Japanese exports fell by 19.2% year-over-year. It was only a modest improvement from June’s -26.2% and not much different from April’s -21.9%.

Like the WTO’s figures, Japan’s have suggested not as deep of bottom (where other places have; see below at the bottom) – but now not as steep of a rebound, either.

Those exports estimates for July include several months of reopening to go along with enormous “floods” of “stimulus”, both fiscal and monetary, in practically every part of the world. The Japanese have been a dependable global bellwether for especially gauging trade conditions more broadly.

Japan, so far, isn’t proving to be an outlier meaning that this lethargic rebound can’t be blamed on the yen or specifically Japanese factors.

While global trade isn’t the whole of the global economy, a globalized economy is often directed by how much trade takes place within it. Ever since 2007, and even before, the overall trajectory for the world has been set by these massive volumes being sent from one place to another and back again.

The world isn’t all trade, but at the all-important margins it does run on trade. Therefore, should the “L” scenario within it prove to be the case, then that bodes ill for the whole rest of the global economy. Just like 2018 when globally synchronized growth was universally projected to liftoff into accelerated expansion worldwide, Euro$ #4 had already turned it around (as you can plainly observe in places like Germany as well as Japan) and into a globally synchronized downturn months before the term “trade wars” entered anyone’s vocabulary.

Without a turnaround in trade there won’t be enough momentum, at the very least, for a completer and more thorough turnaround in everything else. And that’s the nightmare, not the depths of Q2 2020 rather the time it might take getting out of them. If the world economy spends any prolonged period just trying to get back to where it was in Q4 2019, as increasingly looks likely, more shoes will drop.

I wrote this nearly four months ago:

No one is downplaying the severity of the situation, even the worst offenders deserve some limited credit here. Where they’ve offended is in overplaying both the starting position and then their ability to limit the downside and pick everything back up on the other side. In between is not really the issue.

We’re only getting data on the first part of it, and already it’s enough to make you sick. They bungled 2008, badly. They botched everything about the last two years. And now the first steps into the current crisis couldn’t have gone worse.

The depths of the current crisis may not be as bad (and yet they still may be), but in the end it’s where we go from there which is, as I said, everything – and everything is (still) going against us.

Stay In Touch