China’s Caixin Composite PMI came down a little bit in the month of September 2020. According to the latest update, the country’s manufacturing sector index declined by a small amount while services accelerated only modestly. Combined, the manufacturing side worked out to contribute more to the composite than services, so the score for last month dropped to 54.5 from 55.1 in August.

You wouldn’t know it from the press release which covered only the one part:

China’s services activity expanded at the fastest pace in three months in September with a sustained increase in total new business, a Caixin-sponsored survey showed Friday, adding to signs that the sector’s post-epidemic recovery is gathering speed. [emphasis added]

For news outlets that reported on the composite as a whole, it wasn’t much better. Recovery. Up sharply. Soaring. These are the terms you see frequently associated with Caixin’s PMI’s in particular. Technically, you could make the case that these interpretations are being used appropriately.

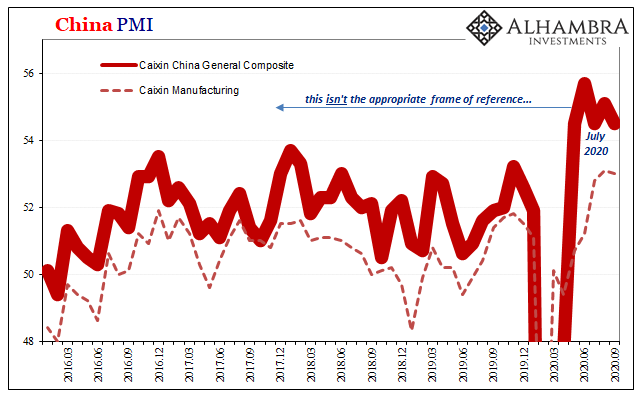

Take a look:

It certainly looks terrific from the point of view carved out above. In the middle 50’s for all three, manufacturing plus services thus the composite, these are levels none of the indices have reached in a very long time.

How is that not soaring?

In the US and European PMI’s, theirs can’t even manage to equal 2017-18’s lackluster growth conditions. Here in China, in these particular surveys which are focused on the “private” economy, the more medium and small businesses beyond the state-owned behemoths, the Caixin PMI’s have overflown not just 2017-18 but also 2013-14.

At first glance, it seems pretty darn V-like.

Unfortunately, it’s not. Being slightly better than the troubling Chinese economy of the last decade would be great if it was following a modest downturn like the one China experienced at that tail end of 2015 and beginning 2016. If there had been a 55 or 56 in the Caixin figures in late 2016, that would’ve been at least somewhat consistent with what everyone had in mind heading toward 2017’s globally synchronized growth.

What everyone had in mind was stimulus actually working as intended, for once.

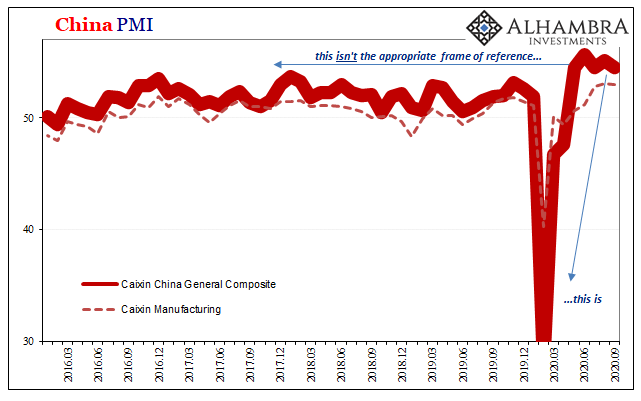

Instead, while 54.5 looks awesome by comparison to the continuous lethargic failure up to and including early 2020, it looks downright short of the goal when seen from the proper perspective of February, March, and April.

Where are the 60’s? The 70’s?

Not only do such true V-like PMI numbers remain elusive, in China as everywhere else, there’s another perhaps even bigger problem once more showing up in these kinds of figures. The Caixin Composite, you’ll notice, peaked all the way back in June, meaning for the entire three summer months it’s been sideways at this already-insufficient level.

A potential slowdown way, way short of the goal in yet another set of global economic accounts – and those for a country who should be far and away leading the way back from where it all started earlier this year. China has had a two to three-month lead since COVID, and the unnecessarily panicked response to it, showed up there first.

This right here is pretty good example of why the mainstream narrative has changed so much in the past few weeks. It started out like this: the economy was turned off like flipping a switch, pure non-economic reasons using China’s coronavirus-fighting example. Thus, since shutdown itself is only non-economic in nature it should be relatively easy to flip the switch back on so that within no time at all everything just goes right back to where it was almost on autopilot.

And then just to make sure, every central bank and central government around the world, China’s, too, conducted “stimulus” of often massive size (not China’s, curiously) which was supposed to have guaranteed the success of this original “V” trend.

But since summertime, more and more we see pretty conclusively how that never happened. They flipped the switch and out popped gigantic positives, sure, including the “soaring” PMI’s of China’s Caixin, but it’s sluggishness and now the slowdown way short of the finish line which has actually been the whole thing.

In response to the latter, forget the former, the “V” narrative has undergone a sizable alteration of late. The first “V” didn’t work out, but so what? The failure of it can only mean more stimulus! Hurray!!

Central bankers and governments have, obviously, obliged this new “V” format without, equally obviously, addressing its very obvious shortcomings. Stimulus was already supposed have worked once, keeping that first “V” on track, it didn’t work so new “stimulus” will allegedly guarantee instead what is really a second shot at a lesser “V.”

Here we are yet again staring in the face of another outbreak of QE2 syndrome. The first one, whatever form of stimulus, didn’t work so we’re told to celebrate how it didn’t by welcoming the same ineffective idea done twice (or more). It’s not rational, it’s rationalizing. And it might work well in certain markets, like Western equities, but for workers and the labor market pretty much everywhere it’s a repugnant and harmful sideshow.

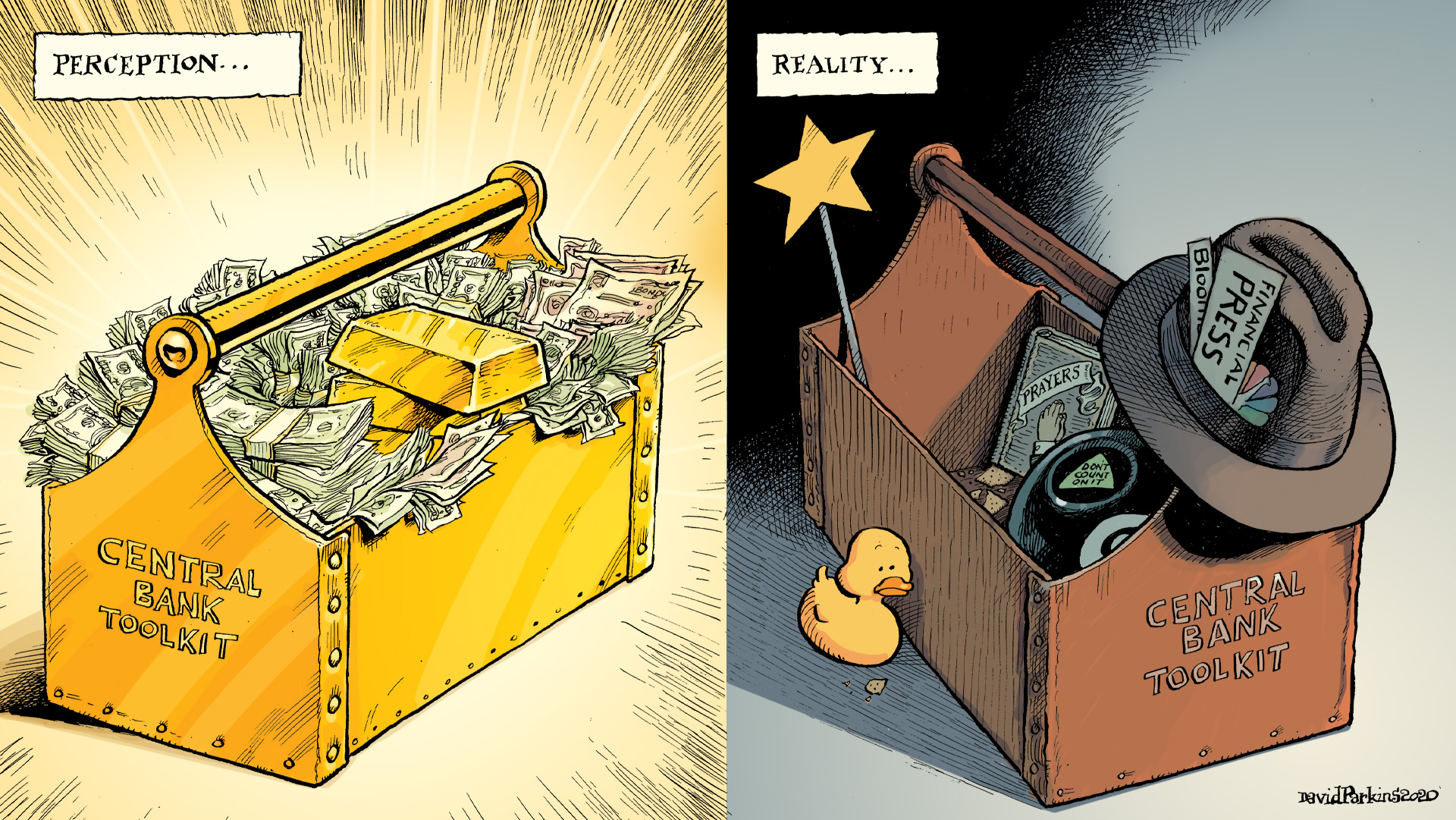

For one thing, these central bankers have no idea how QE’s supposed to work, either! I’m not making this up. I already wrote about Bill Dudley’s 2014 testimony to that effect.

Here’s a recent study published by the Federal Reserve about the Fed’s infatuation with the Effective Lower Bound (ELB) and thus QE’s role in circumventing it especially when this ELB is down close to the ZLB (Zero Lower Bound). Published at the end of August concurrent with the updated inflation targeting nonsense, author Michael Kiley sums QE up this way:

Within the DSGE model, QE stabilizes markets through relaxation of financial constraints facing financial intermediaries, in a manner akin to the mechanisms that appear to have motivated Federal Reserve actions.

Catch that? That second clause is a doozy, a true beauty of a dodge. How does QE work? What Kiley is saying is that they don’t really know, but QE just fixes whatever is wrong; “in a manner akin to the mechanisms that appear to have motivated Federal Reserve actions.”

In his words, something happens in financial markets unleashing “financial constraints” on financial intermediaries, provoking the Federal Reserve to respond with QE, and whatever that something is QE just magically focuses on “the mechanisms” that have gone wrong and takes care of them freeing up the financial intermediaries to keep feeding credit to productive economic investment (the macro association DSGE models associate with financial markets and intermediaries).

That’s some serious deus ex machina right here.

They have no idea how it works so they just assume that it does in whatever way the world needs before plugging that assumption into the DSGE models which spit out numbers which sound objective enough to further the fairy tale about successful policy programs even as those same models struggle to explain the lack of full recovery (R*) in QE’s wake everywhere QE ends up being tried.

The reason to bring up Kiley’s work here is that it has caught some recent attention, though not for these reasons. According to the simulations he ran, constrained at the ELB close to the ZLB, as the US system finds itself right now, this means QE would have to be extra-huge in order to give monetary policy any chance to overcome such a large demand shock. With the first “V” narrative falling apart, and on to the second version, Kiley’s estimates might be seen as an official Jay Powell roadmap.

Perhaps twice as much as what’s already been done by the Fed. Party-time, baby!

More seriously, this is hugely important, such huge scaling because:

Additionally, the medium-term scarring on economic potential can be large, and mitigation of such effects involves persistently accommodative monetary policy to support investment and long-run productive capacity.

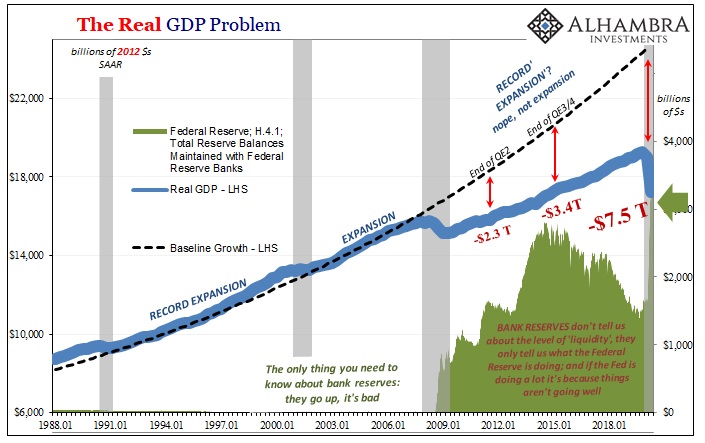

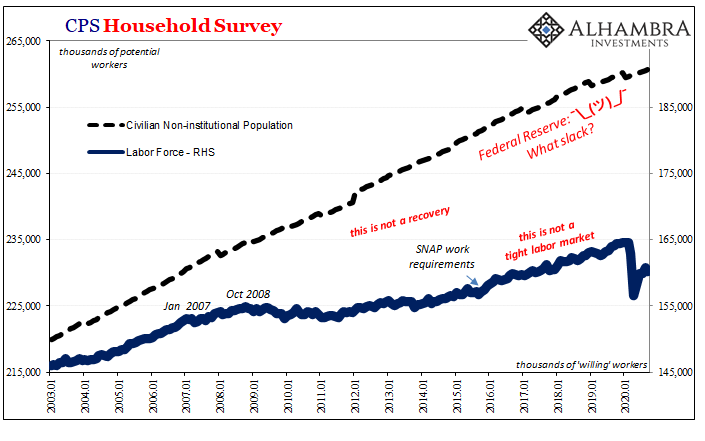

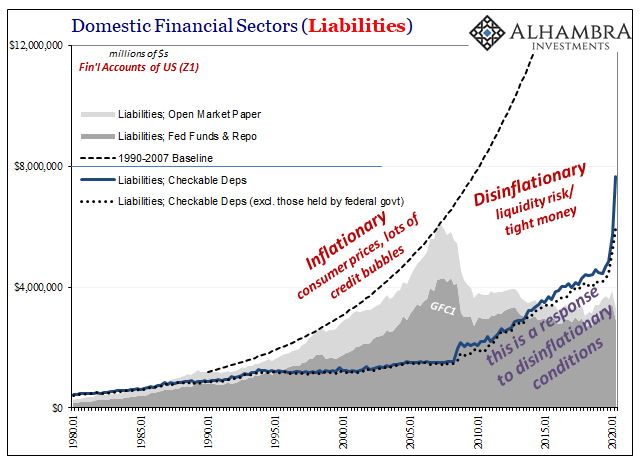

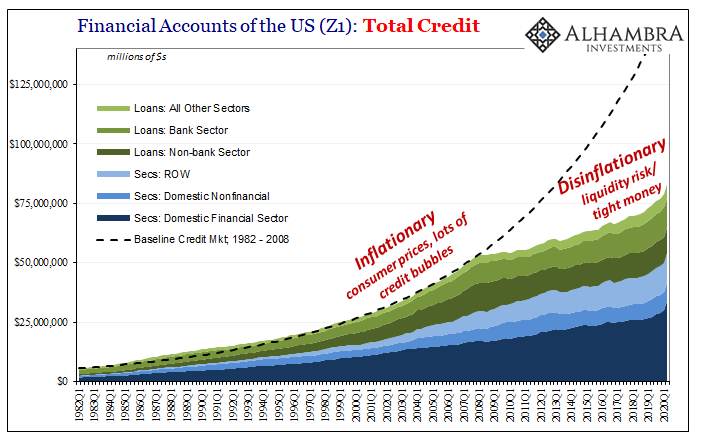

In other words, if “stimulus” isn’t effective then the economic damage the unmitigated shock might cause can be severe and more than short run. You don’t need statistical models to tell you that, we’ve got tons of receipts:

Which brings us back to the second try at a “V.” The first dose of “stimulus”, monetary plus fiscal, in the US like China didn’t do it. That much is apparent just by the change to the “V” narrative itself.

So, we’re told more of the same is cause for broad, uniform optimism when perhaps it instead leads us to a necessary second look more toward the direction of “medium-term scarring on economic potential” which Kiley admitted “can be large.” Just what happened when QE1 fell flat leading instead to QE2 then 3 and 4 but never recovery.

We still haven’t recovered from “the mechanisms that appear to have motivated Federal Reserve actions” a dozen years ago which is obviously relevant to those same actions and motivations appearing in 2020 (as well as, importantly, last year in 2019). The QE2 syndrome is actually a stark warning; if these people are “motivated” to do what they call “stimulus” for a second time (and more) it just isn’t a good sign at all.

Put that back together with the ludicrous change in “V” narrative, and we’re living an economically Orwellian orgy. They said “stimulus” would make the first “V” an easy accomplishment, but when it didn’t the promises of more “stimulus” and now a smaller “V” are both guaranteed again and supposedly worth even greater excitement.

This is “a manner akin” to pure madness. Sadly, however, it’s not unexpected even after the last dozen years of intellectual, and economic, darkness. The utter ridiculousness of interest rate targeting on the one hand, and the pure sophistry about QE on the other. These are actually what is anchoring the new “V” optimism. Jack’s infatuation with his beanstalk made more sense.

Stay In Touch