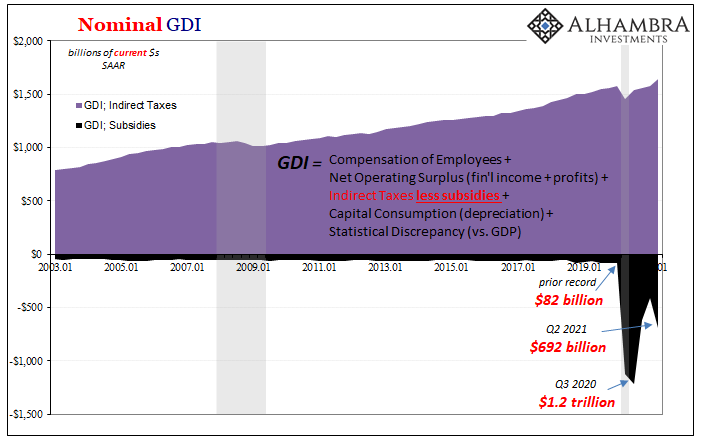

The second estimate for second quarter 2021 GDP didn’t change much, or anything. However, coincident with this “expenditure side” data release the BEA also completed its full preliminary assessments of the “income side.” GDI, in other words.

What’s interesting on this other side of the output ledger is something called Net Operating Surplus (NOS). And it is NOS which frustratingly takes the additional month for the estimate to appear among the GDI line items.

What is NOS? What is GDI?

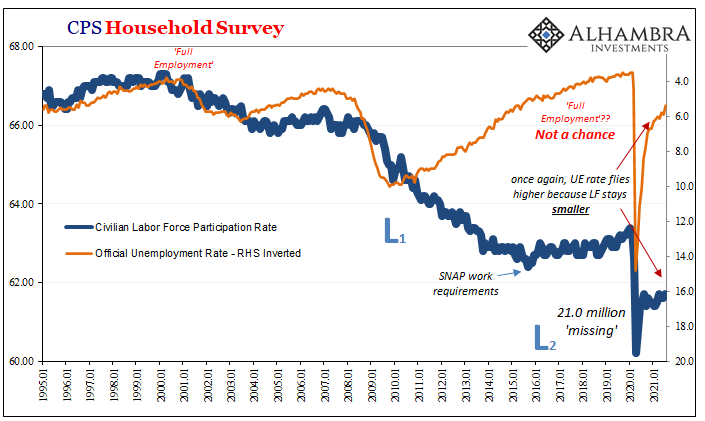

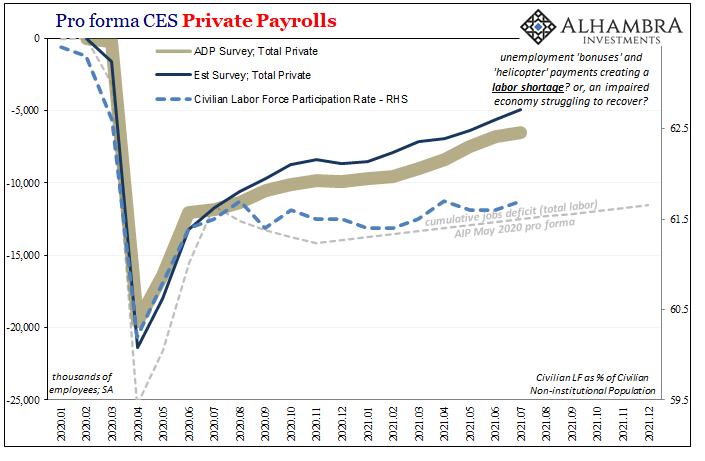

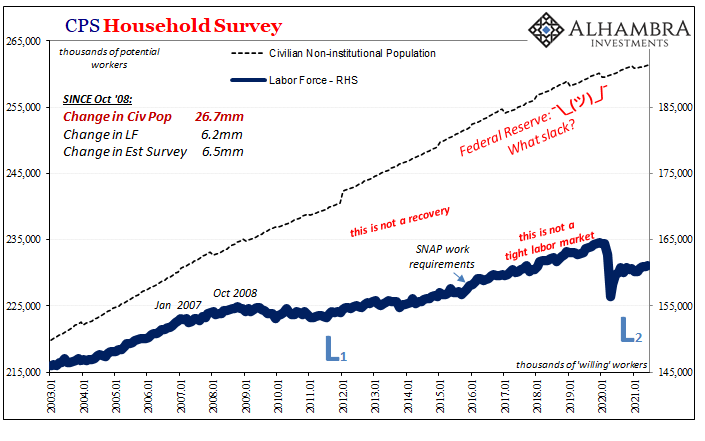

I went through the accounting last October fishing for data which might best explain the discrepancies between GDP (or I) and lackluster labor. The media had, and still has, whichever wave of COVID and nowadays lazy Americans who don’t want to work for the additional $300 UI weekly, with which to make a weak economy fit the strong narrative.

Neither of those seem to me anywhere close to completely explanatory.

Further waves of COVID and generous benefits paid to idle workers are part of it, but they cannot be all of it; where “it” is the labor data aside from the unemployment rate and Establishment Survey.

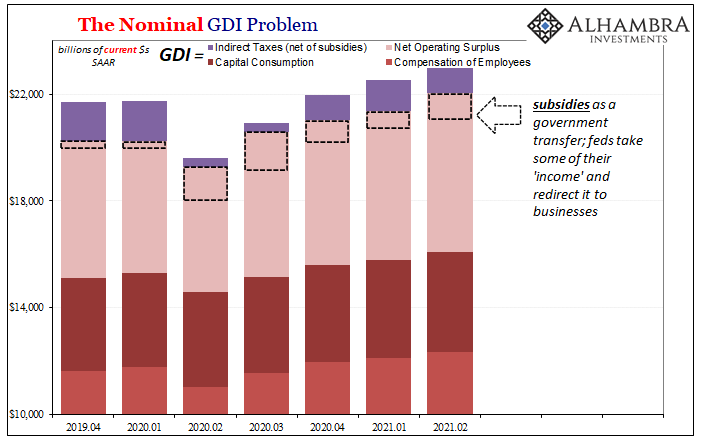

We already know corporate profits are up, some of them way up. But GDI exposes Uncle Sam’s piece and therefore might tell us something important about why maybe companies aren’t hiring or paying higher wages like they otherwise might have been if NOS wasn’t so stuffed with artificial subsidies.

That’s the crux of the disturbance; quite simply, businesses might logically and rationally view their profitability derived in some substantial part from these subsidies as temporary and therefore have been acting accordingly (a sort of Permanent Income Hypothesis for the company bottom lines). If we comb through GDI and make the necessary adjustments, what might that reveal of non-subsidy profitability and cash flow?

First, I’ll review the simplified explanation of GDI accounting (if you want the whole thing, it is here and here):

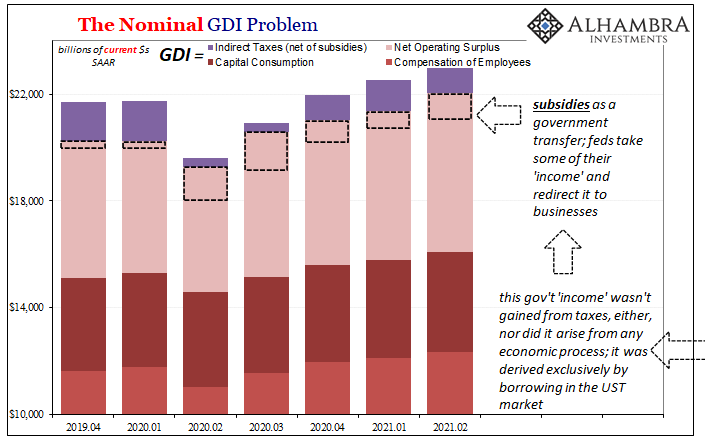

GDI consists of wages and other forms of labor compensation (including 401k contributions, among many) plus something called the Net Operating Surplus (NOS), which is really financial income along with corporate and business profits. Combined, those give us the net domestic product (at factor cost).

To that net we add indirect taxation (taxes on production and imports). These are counted rather than subtracted because in GDP/GDI accounting the government has its own income stream to pay (partly) for expenses included on the expenditure side. The balance of these taxes, however, gets reduced by subsidies paid to industries (which will become very important in a minute).

Subsidies amount to a transfer payment, and GDI doesn’t do transfers because they would be a kind of double counting. In other words, the transfers, subsidies in this case, already show up largely in corporate pockets tabulated already under the NOS.

What’s left is to add capital consumption (depreciation) and altogether we have GDI (and then a statistical discrepancy compared to GDP).

The second quarter update begins with rising GDI, rising NOS, and another large dollop of government influence. Taking the last first, the BEA believes that these transfers amounted to a seasonally-adjusted annual rate of nearly $700 billion in Q2. That was up from $400 billion in Q1, closer to the max (Q3 2020) than what used to be normal.

As I pointed out back in October, we aren’t “supposed to” deduct subsidies from anything, but I’m doing so as a back-of-the-napkin sort of calculation to get a rough sense of how much the government may be contributing to the overall financial/profit condition of the business sector.

Perhaps just as importantly, we also need to keep in mind that the funding source for these transfers is not taxation drawn from greatly increased economic activity. On the contrary, they are and have been financed by borrowing in the UST market (“good” thing the government has been able to take advantage of painfully consistent deflationary potential through collateral scarcity and liquidity concerns driving these bond prices up and keeping them up no matter how many times we hear “too many Treasuries” and inflation demands).

This means that such non-economic borrowing is finding its way via several steps into the purported economic well-being of the nation’s businesses. GDI like GDP doesn’t distinguish, but I still believe that rational businesses almost certainly do.

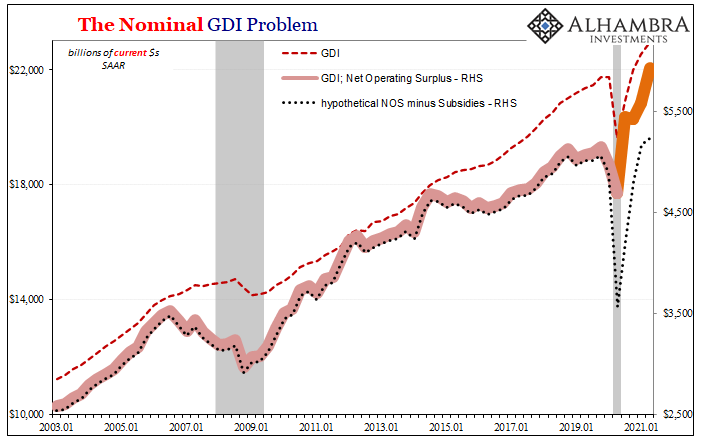

Therefore, again very roughly speaking, the BEA’s estimate for NOS shorn of subsidies embedded within it doesn’t look at all like overall NOS. On the contrary, taking them into account (dotted line above) we find that the aggregate operating condition while much better than last year’s recession isn’t anywhere close to including the federal government’s transfers in it.

And in Q2, the incremental gain was slight, meaning most of it accounted for by Treasury’s checkbook: total NOS increased at a SAAR of $350 billion Q2 from Q1, but subsidies rose $286 billion leaving a “not artificial” gain of only $64 billion.

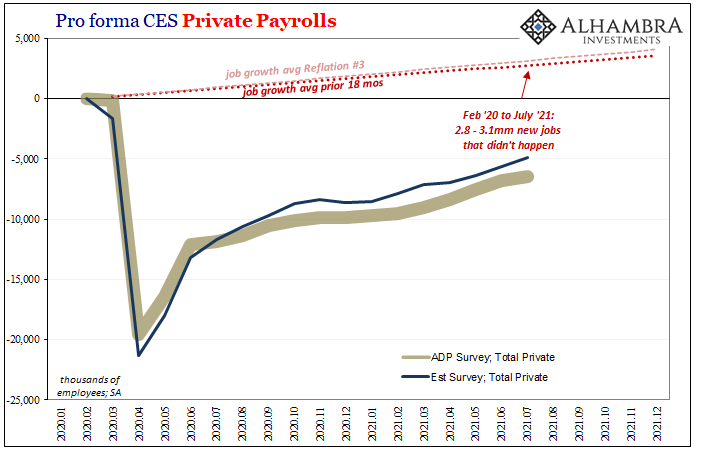

Furthermore, not in the GDI nor GDP data here, the vast majority of the economic contributions to the rebound in NOS was due to mass layoffs and the continuation (nearing a year and a half) of the huge jobs deficit ever since them. On top of that deficit, also several million more jobs that never happened which would’ve cost employers a chunk of the NOS.

You can see why the labor market situation may not quite be adding up.

In short, much of what has driven the rebound in NOS – if you believe what I’ve done here – is the combination of one artificial factor (Mnuchin now Yellen) with a 2008-style you-hate-to-see-it round of labor destruction which might be more permanent than not.

It is certainly debatable, but I have to believe this better explains the world of 2021 than COVID and unemployment payments. At the end of the day, there is no labor shortage, there are businesses who resist (because they can’t or if they can they may believe they can only for a short time under specific conditions) paying the market-clearing wage.

An eye on GDI might tell us a lot about why (sorry for that).

Stay In Touch