The second most-often question I get asked is, OK, smart guy, since you say the current eurodollar system is irrevocably broken, what do we do about it? [This comes right after the most popular question, um, what is a eurodollar?] I typically avoid answering for two reasons. First, since hardly anyone is ready for the first question, it is somewhat wasted effort to begin seriously game planning into the second query.

The second reason is crypto. I find enormous potential future possibilities particularly where digital technology can offer a solution to what it is that is broken about the eurodollar. However, this then gets mixed up in the current pricing bonanza (bubble) of so many various digital schemes, many of whom won’t survive, which I believe is a totally separate (and misguided) issue.

Briefly, investors and speculators have piled into the crypto space believing they need shelter from some looming dollar collapse (which is always just around the corner). In other words, the store of value function for what people hope is a functioning digital money. In the current frame for discussion, it’s sometimes impossible to get past this gross misperception.

The dollar, or should I say, eurodollar, isn’t going anywhere, not yet.

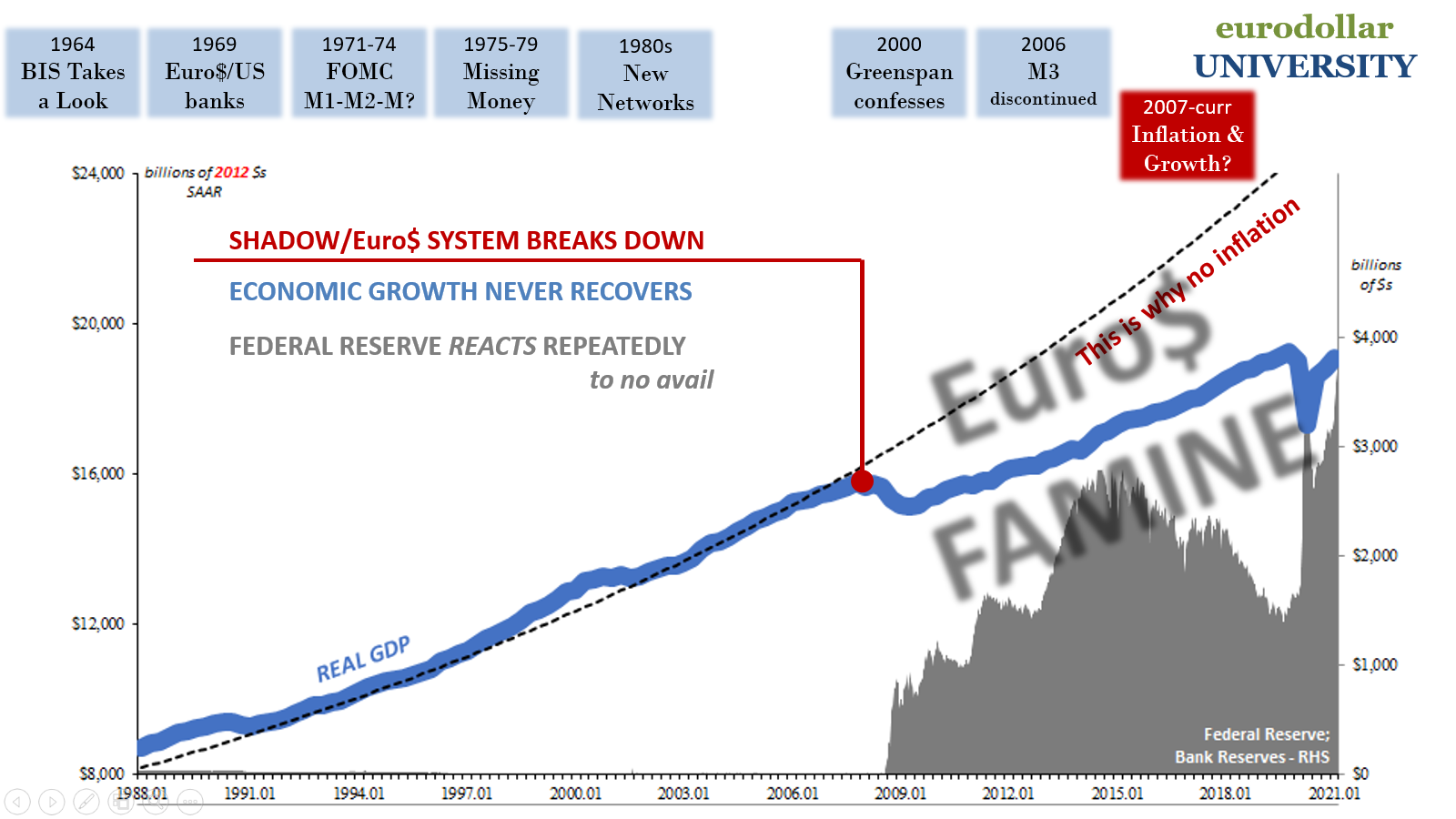

And that’s both the problem as well as the opportunity. The malfunctioning eurodollar (since August 9, 2007; a breakdown forewarned a year earlier by inverted curves, among other things) has opened the door for a competing currency system – but there are no realistic alternatives anywhere close to ready to fill the bill (pardon the pun).

This isn’t store of value money, it is medium of exchange along with, to a substantial degree, its unit of account. There is where many people get the current eurodollar arrangement all wrong; it doesn’t really have any store of value function, such was handed off to financial markets (especially Eurobonds) long, long ago.

And that’s another fertile subject for another day (including how repo therefore collateral is basically the link between store of value in the eurodollar becoming a useful medium for exchange).

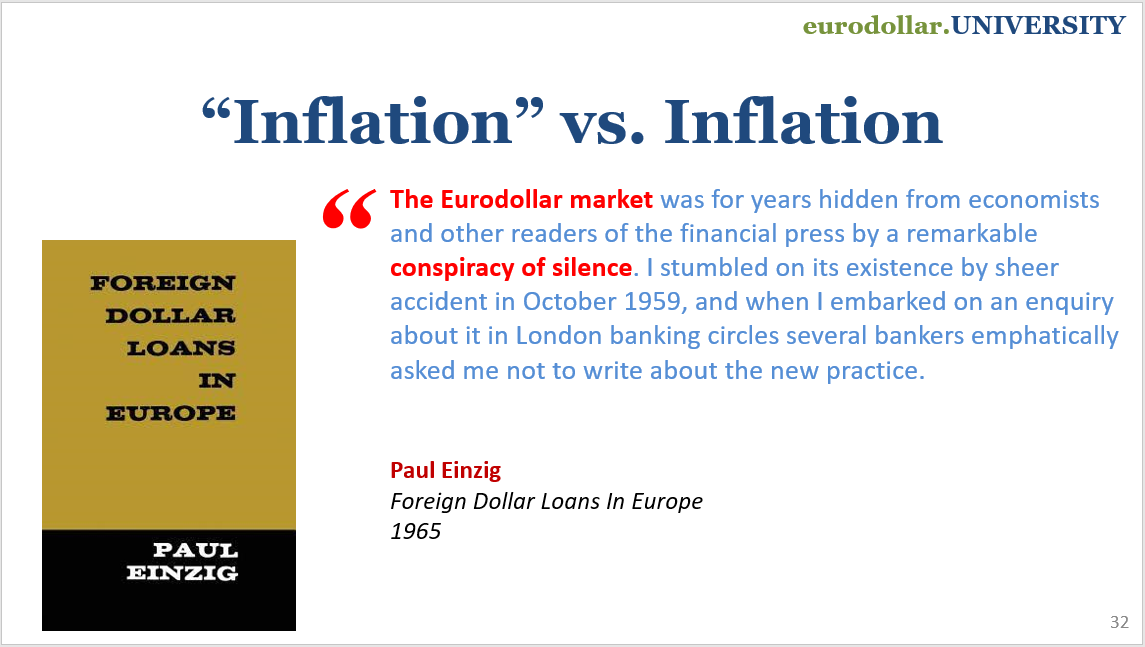

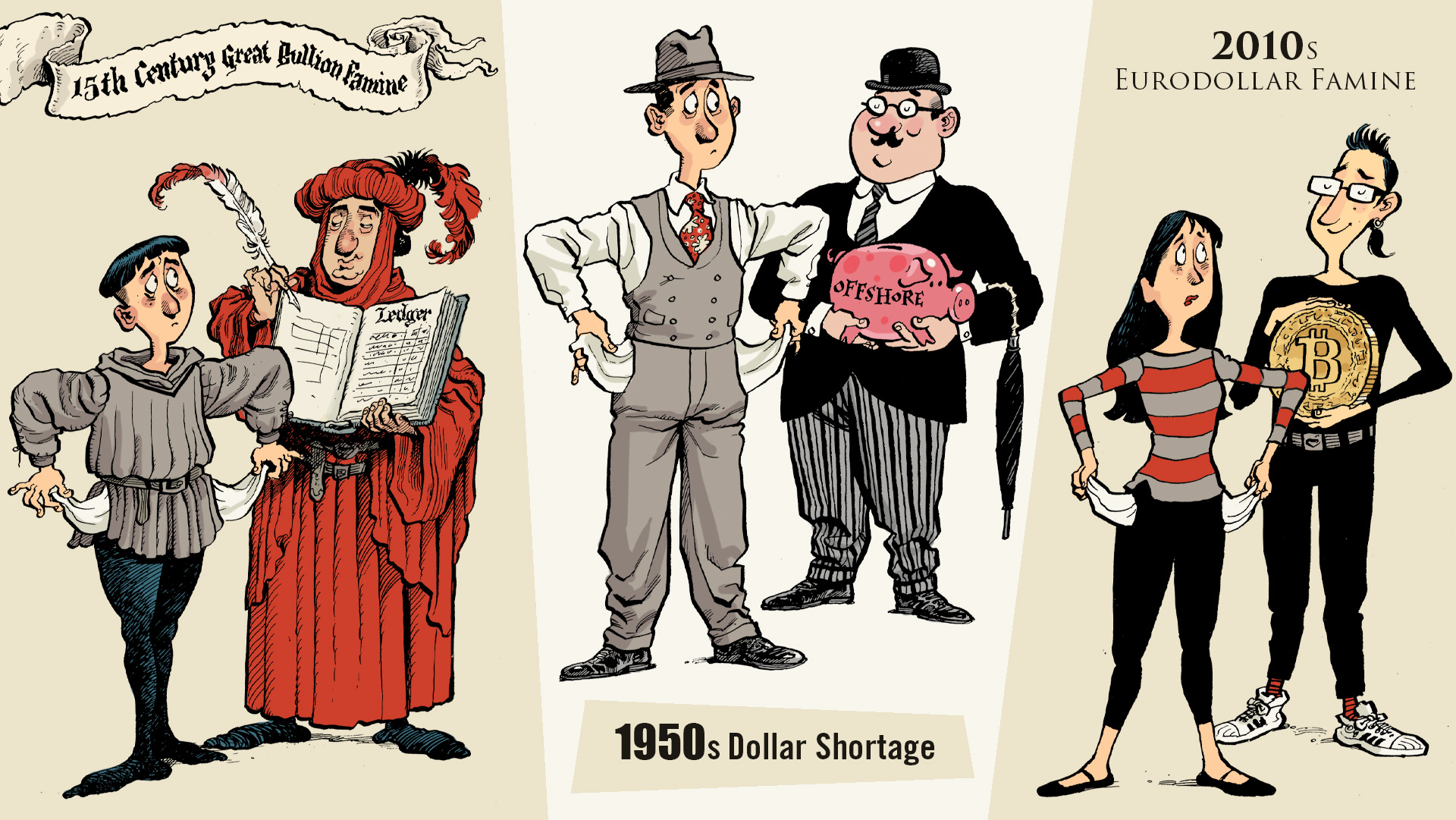

The eurodollar is a form of fictive currency, or ghost money. Basically, a ledger system which arose in response to the tight money era during Bretton Woods’ short run (Triffin’s Paradox). By elegantly getting around Triffin and gold exchange, the eurodollar proliferated as a pure ledger arrangement.

In doing so, however, it sowed the seeds of its inevitable demise; inherent instability which needs to be addressed as a medium of potential exchange.

To see what I mean, and to hopefully better understand why some digital currency format of the future might be an eventual suitable replacement, instead of getting lost in the myriad of details behind the ledgers and the historical proliferation of products which make up the current monetary system, today we’ll stick to just big picture concepts.

Start with the high level theory and eventually work our way down from there.

Money itself is not wealth or riches, rather these are tokens, a useful tool for managing efficient commercial transactions; the machinery of exchange, as someone (Henry George) once wrote.

Under a hard money or fixed money system, it was hard to come by – and that was its whole point.

Unfortunately, scarce money, while alluring as a romanticized ideal (I know, I was there in my youth), historically it always ends up in a mess. Restricted, static money tends to pool at the worst times, hoarded which then becomes deflationary currency and then deflationary economy.

Depression. The worst of the worst, all-too-frequently.

The banking system, in part, became fractional reserve as a means to achieve a greater level of elasticity – to take some of the sting out of those times when hoarding rears its ugly deflationary head.

An obvious downside to elasticity is the potential for too much currency, or inflation (including asset prices, which we won’t get into here); the very outcome hard money advocates seek to avoid. Either way, the money creation function is either wholly exogenous (hard money) or partly so, meaning some form of currency to be issued from money reserves by almost always private banks.

The whole purpose of the monetary system is to most efficiently match the supply of money/currency with the productive demand for it. This is where the intermediation function is supposed to come into play as distinct from money creation.

There are, or used to be, specialists who, while nowhere near perfect, could better match (using all manner of financial indications) the supply of money with legitimate demand for it. Not always banks, sometimes just wealthy individuals, either way a system-wide process of sorting the good potential real economy and financial projects from the utter insane and doomed-to-fail.

Any economy without intermediation is itself doomed when too much stupid and insane poisons the process (exactly the hard money argument).

Under a fractional reserve system, banks were specialized as to this intermediation, but also undertaking a partial role in the money creation function, too (the actual fractioning of reserves). With limitations provided by limited abilities to expand money and the discipline required by it, intermediation was, in reality, a relatively healthier combination of sorting economic and financial projects.

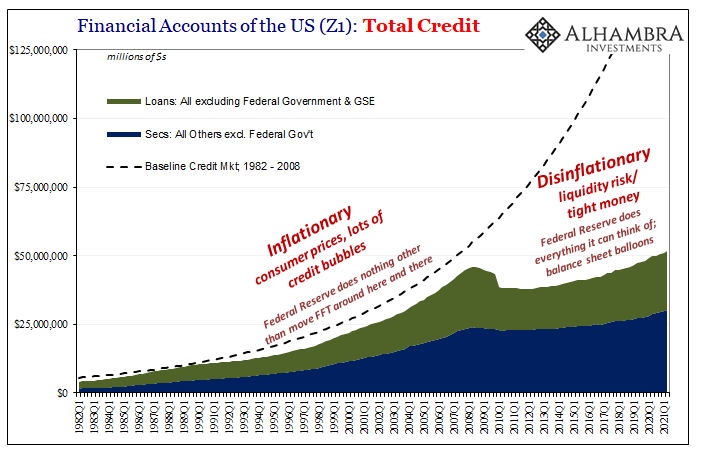

The rise of the eurodollar, however, totally upended these relationships and roles. As a reserve-less, ledger (or ghost) money system, the intermediation function of banking was then combined with the money creation function in total.

It was a recipe for, quite literally, inflationary currency (see: Great Inflation). Yet, it found its footing, or another one, eventually when in the eighties some more effective intermediation was briefly reintroduced despite maintaining a full handle on the money creation function (the public kept entirely in the dark about this).

The combining of the two major functions perhaps predictably grew out of hand once again especially around the late nineties (as the products were really proliferating), which simply meant that banks and the systemic ledger could grow (mostly) unconstrained. When doing so, it overwhelmed its latter sense of intermediation: overabundant ledger money supply leading to anyone and everyone getting money, loans, or whatever form of credit; that’s how we ended up with something like subprime NINJA mortgages.

The more money created on the global eurodollar ledger, the more it appeared to be safe to do increasingly stupid things along the way – intermediation was effective obsoleted by that unlimited money potential. Because the money creation function had gotten so out of hand, it seemed to even the most formerly prudent participants (like HSBC, for example) there was no more need to intermediate since everything, including the insane stuff, just seemed to work out more than fine.

But only so long as the money creation function could keep on unimpaired.

Thus, August 9, 2007, really was as if the world stopped.

We don’t need to go into the details of the first GFC here, either, again just as a top-level review we need only acknowledge how despite the impairment in the systemic money creation function (balance sheet capacities, therefore ledger) the intermediation function was left right where it had been before. Nothing was done to re-separate out the two.

In fact, everything about every official non-money monetary policy response from whichever “central bank” pretending to be a central bank was about getting the public, mostly, to believe we would, by bank reserves alone (QE), just go back to before the crisis and reset.

As if it would be 2005 again, only this time without all the subprime mortgages.

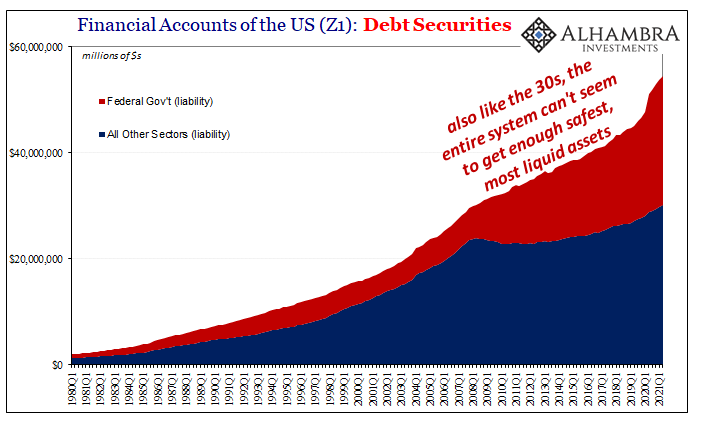

In reality, with an unfixable money creation function still paired inside the banking system (acknowledging the secondary role of bond markets and non-banks) with intermediation, the risk pendulum quite understandably swung entirely in the other direction: we went from unlimited, or nearly so, bank-created ledger money overwhelming intermediation to chronically impaired ledger money making risks so high, reality as well as perception, there’s no point in even doing intermediation since the (risk-adjusted) returns aren’t going to be worth the effort.

Pre-crisis, therefore, no intermediation leading to everyone getting as much credit/debt as they could handle to post-crisis no intermediation leaving out most of the rest apart from only the safest and most liquid borrowers.

This is, of course, the details behind the interest rate fallacy – interest costs we all track for those safe and liquid, such as governments, fall and stay low while the effective costs for riskier borrowers (not just Mom and Pop tiny firms) which we never see because those costs are prohibitively high, and so the intermediation never happens.

Low rates do not equal stimulus, they are a systemic nod to the breakdown in money creation blighting, in the opposite way from before 2007, intermediation.

In very simple terms, for our purposes, the high-level answer is to back out the money creation function from the intermediation function. This doesn’t necessarily mean we have to go back to where banks are intermediating some exogenous money creation(s) – but it doesn’t necessarily preclude the option, either.

On the other hand, since we’re already on a distributed ledger money system, the eurodollar, and have been for more than half a century, digital currencies just might hold some legit promise possibly even as an overlay to existing methods; as a more widely distributed ledger which doesn’t require specialized businesses like banks to keep track of transactions on our behalf (that’s all modern-day banks really are, glorified bookkeepers).

Bookkeeping is easily replaced. Blockchain.

And the money creation function to go along with it can be encoded in the form of whatever digital currency itself – something, believe it or not, which is already being done on a primitive basis.

I’m talking about technology which already exists, digital currency formats like algorithmic stablecoins. While I don’t think these are ready for primetime, either, they are a step – perhaps giant leap – absolutely in the right direction (a topic for another day; briefly, my objection is that they attempt to match demand and supply for the coins by holding the coin’s price stable; a more advanced therefore realistic systemic stablecoin of the future would have to consider far more than a stable coin price)

Again, the goal is to efficiently match the supply of money with reasonable demand for it. And, as discussed above, “reasonable demand” is left for intermediation. Whether some form of next-step banking or, potentially, decentralized finance – defi.

A highly intelligent and complex algorithmic stablecoin system running alongside defi credit pathways, dynamic (not static) money creation established separately from intermediation, it’s a highly idealized yet potentially viable set of solutions that the more I look into the future the more I see them as at least reachable.

The devil, as always, is in the details; many a slip twixt the cup and the lip.

And there are a potentially overwhelming number of details and schemes left to be studied, broken down, and then worked out. But that’s the good thing, in a sense, given our current broken eurodollar medium of exchange there is enormous opportunity for its replacement, and that is what’s actually driving the technology investments, not the dollar-go-boom store of value belief in each’s price right now.

Given enough time and competition, that opportunity alone is utterly huge incentive, and so the entire digital space will keep moving forward toward what we hope is that unifying point; in this case meaning smartly separating those deeply fundamental monetary functions that were jumbled together in the backrooms of London City almost seventy years ago with hardly anyone ever noticing, reporting, or monitoring (benign neglect).

In very simple terms, undo the mistakes of the past. Far easier writing about it than actually doing it.

Stay In Touch