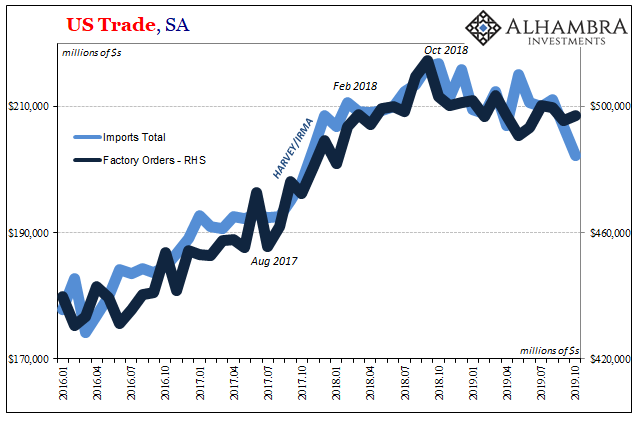

For US importers, October is their month. And it makes perfect sense how it would be. With the Christmas season about to kick into full swing each and every November, the time for retailers to stock up in hearty anticipation is in the weeks beforehand. The goods, a good many future Christmas presents, find themselves in transit from all over the world during the month of October.

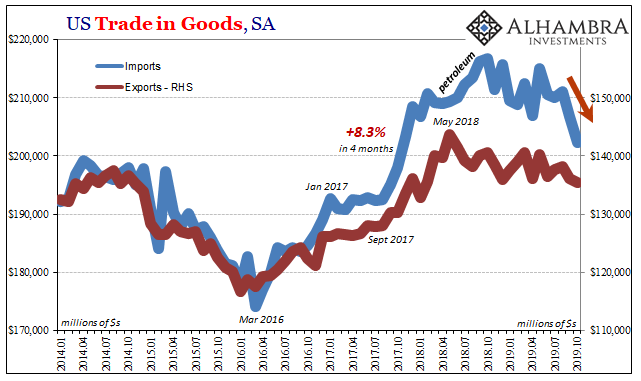

For the Census Bureau’s trade data, that means this is the month that shines above all the rest. The greatest monthly totals for any year can be found during it. The big one, the top dog. According to the latest estimates for 2019’s turn, that is still likely to be the case. And that would be a big problem.

Americans still love to spend on Christmas. Jay Powell keeps saying the economy is strong and we can all thank the underlying labor market for that. Strong labor market should mean great Christmas in the goods economy.

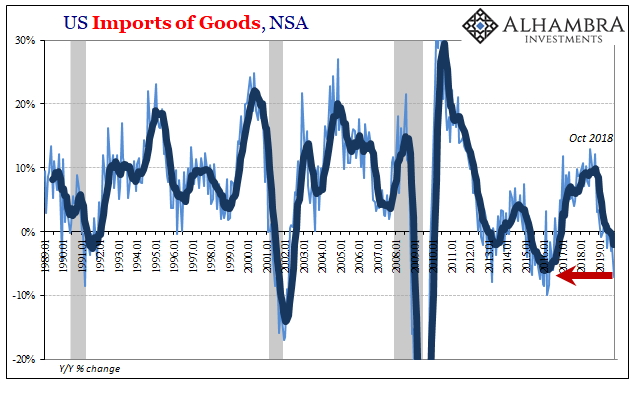

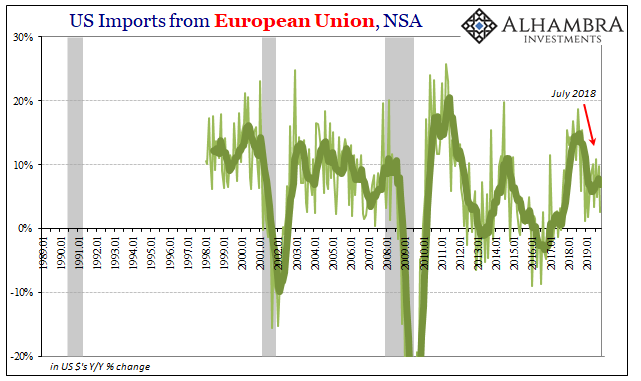

But if that was in any way true, how does he explain such a pitiful October on the import side? If retailers are expecting big things this holiday season, they sure aren’t acting like it. For this crucial month, Census says US imports were astonishingly 7.2% less than they were during the same month of 2018. Someone is missing something.

A lot of something.

At -7.2% (unadjusted), that puts the current pace more in line with early 2016 and the worst months of Euro$ #3. A time very near to recession. Therefore, hard if not impossible to reconcile that near recession with the current mood dreaming about an upswing.

Talk of recession was near constant a few months ago but has largely disappeared, and yet here we are starting to see the acceleration to the downside all that talk had been anticipating. This isn’t the only account showing that downward acceleration, just another key measure of, or proxy for, broad US demand.

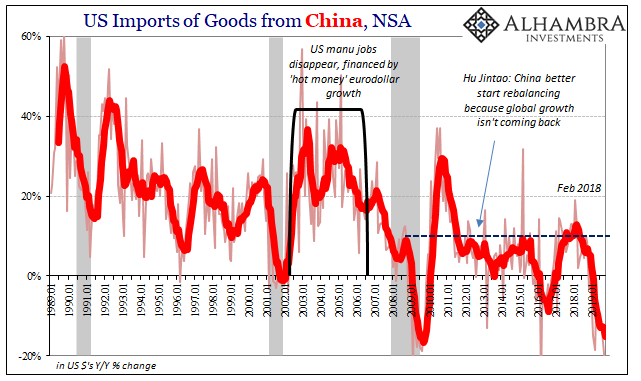

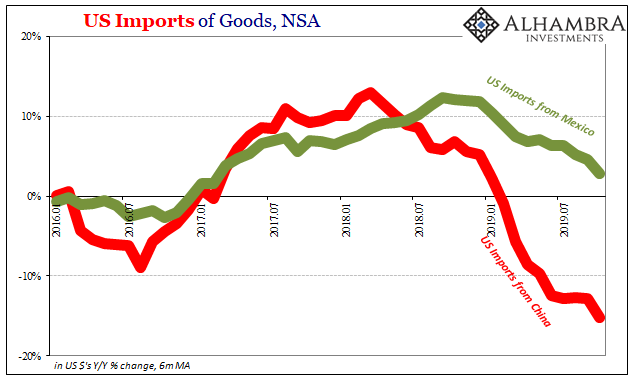

And it doesn’t make any sense in terms of the dollar or trade wars, as they are conventionally understood. A rising dollar means imported goods should be cheaper to buy; the only place where that’s not true is for those products coming out of China. The trade wars have definitely taken their toll on those routes.

The latest estimates put imports from China down more than 23% year-over-year, a definite squeeze and price-driven distaste. The trade levies are working.

But if Americans are importing so much less from China, why aren’t they importing so much more from other places? Again, the dollar plus the lack of additional tariffs on them should, ceteris paribus, make goods produced elsewhere so much more attractive. There shouldn’t be a big net difference.

What we find, however, is that again there is no such thing as ceteris paribus. A useful assumption for making statistical models, in the real world full of complexities it is an invitation for self-delusion.

A rising dollar does mean relative cheaper imports, but it also means growing serious economic weakness pretty much everywhere around the world. Including the United States. That’s the big (and pretty obvious) correlation left out of the Economics textbook, the more important side of CNY DOWN = BAD (meaning, US$ UP = BAD).

So, while imported goods from, say, Mexico might be cheaper still, there is less and less demand for them at any price (or from, say, Europe).

The US is definitely importing a lot less from China at the same time it is importing now a lot less, period. The one is the minor effect of trade wars (in the overall scheme of things; the Chinese probably don’t think of it as a small issue), the other is the more important and impactful, quite predictable result of the global dollar shortage. The eurodollar squeezing the entire global economy if not all at the same time and in the same way.

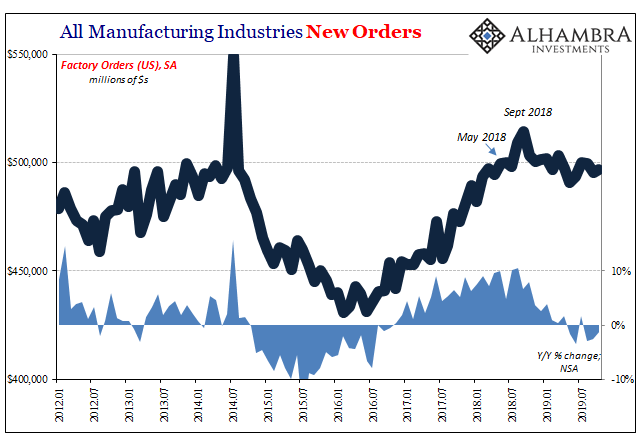

It doesn’t just apply to trade, either. At the same time American businesses are stocking way less of imported goods, they are also demanding less from domestic producers, too. It is, again, overall US demand which is falling.

In the runup to Christmas 2019, retailers have been ordering less from US factories. Factory Orders domestically are now falling steadily and have also seen more downside in recent months than the weakness-is-behind-us narrative would have.

It just doesn’t fit, at all, the view of the labor market being this unbreakable source of strength which, along with three and only three rate cuts, will see us all through a temporary, “transitory” mild patch of uncertainty.

This is now a full downturn, plain and simple. The fact that last Christmas was a total bust and retailers aren’t thinking anything better for this one is hardly the projection for a stable economy let alone one that should already be accelerating its way into 2020. The second half rebound never showed up. Shocking, I know.

Globally synchronized downturn took a little while, but, as we’ve said all year, the US was just following places like Germany and China as they absorbed the more immediate effects of the global dollar shortage first. That’s the bad news. The question of recession is mostly academic at this point; how much downside this particular downturn might still have left in it.

Stay In Touch