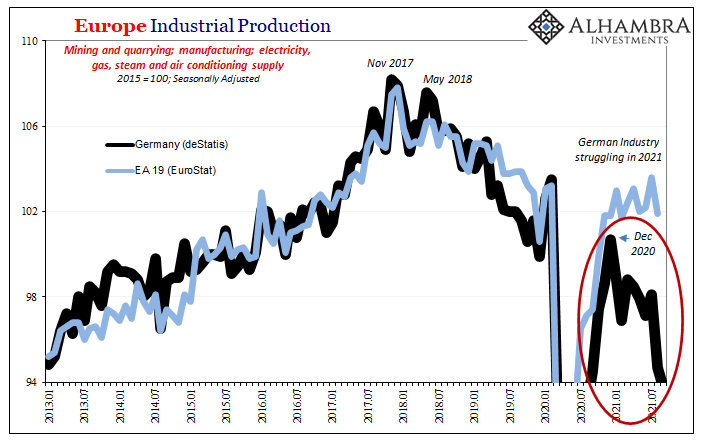

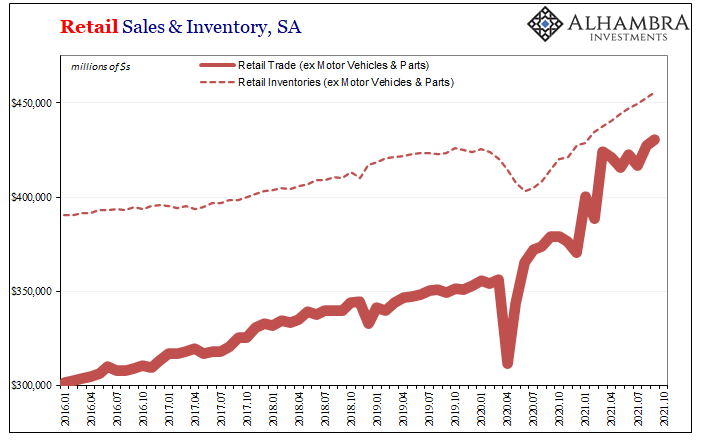

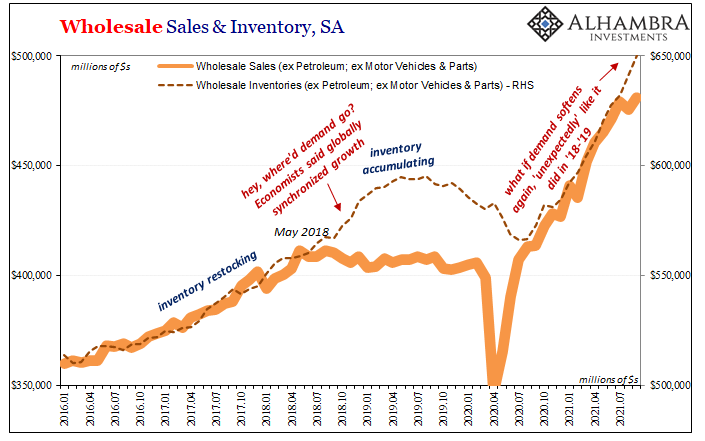

Christmas came early for retailers already experiencing a boom year. This, however, creates a bit of conundrum given that producers have suffered rather than flourished despite such great fortune at the top of the supply chain. In whichever location you look at, production has been at best questionable.

Why?

Theories abound. The mainstream is filled with those like what’s been reported as a labor shortage. With not enough workers, so it is said, this is preventing the production side from more completely matching the rebound in retail sales. Producers desperately want to produce a ton more, they purportedly just can’t seem to entice lazy Americans to get up off their government-fueled vacationer couch.

The flipside of this “inflationary” (non-economic, of course, therefore the quotation marks) boom in demand is the stinging array of costs producers must absorb first. Labor is one and the largest of these, but how much labor can producers truly afford as supply issues bite the commodity space at the opposite end of the supply chain?

Rather than labor shortage, maybe too many around the global production economy feel the same pinch as these sawmillers:

In the United States, sawmills are facing a labor shortage as workers are unwilling to work in such dangerous conditions at low wages.

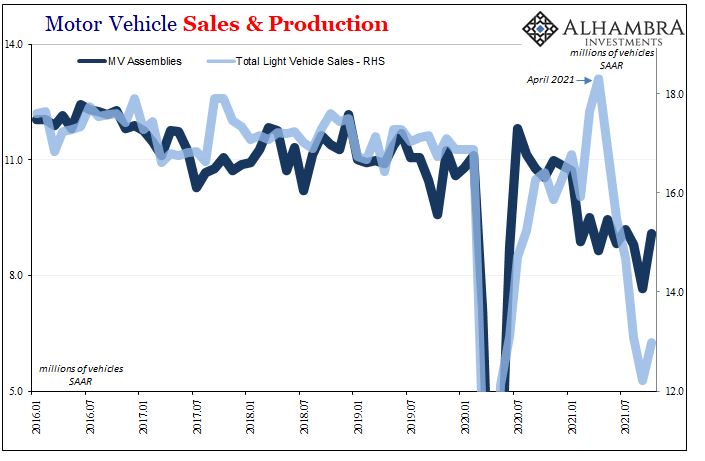

OK, if not necessary a shortage of labor, what about the supply problems? The automobile sector, in particular, is utterly plagued (so we’re told) by grossly inadequate supplies of necessary materials, only beginning with semiconductor chips.

Again, so it goes, producers would be producing a lot more if only they could get their hands on enough raw materials.  Or it might be those on the production side – outside of autos – acting quite cautiously given this overall set of various imbalances only beginning with the hellish costs of those very materials. After all, if prices for certain inputs are rising faster than even the fastest consumer prices paid up at retail and wholesale, profitability actually suffers down here where it all gets made.

Or it might be those on the production side – outside of autos – acting quite cautiously given this overall set of various imbalances only beginning with the hellish costs of those very materials. After all, if prices for certain inputs are rising faster than even the fastest consumer prices paid up at retail and wholesale, profitability actually suffers down here where it all gets made.

In that sense, producers sure would be prudent to proceed cautiously regardless of what the economy appears to be doing in nominal terms.

This would include any additional costly investments otherwise needed to better match current levels of activity, as we noted not long ago.

Part of the problem is post-pandemic behavior; locked down originally due to governmental indifference, consumers began buying even more goods online than they had been prior to 2020. This required retooling much (too much) of the way goods are handled from producer to wholesaler to retail delivery.

It is its own bottleneck that in this environment where costs are outstripping selling prices, creating more capacity might not be such a great idea unless absolutely necessary – especially if anyone isn’t one thousand percent sure the demand for goods is going to be there for the long run in order for all of it to pay off.

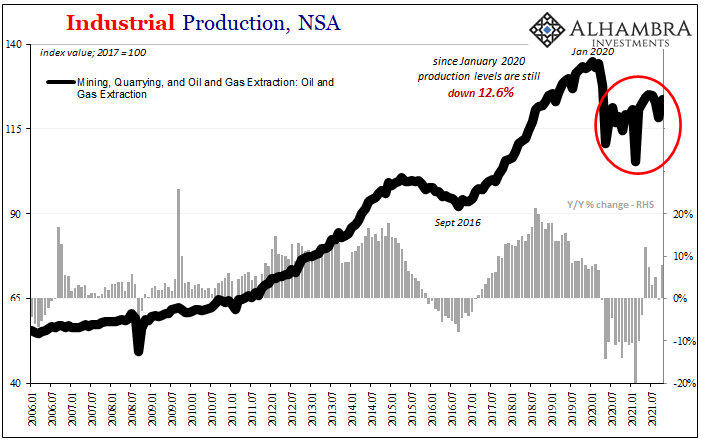

This surely seems to be the case in the energy sector, where selling prices are far more closely matched from top to bottom in the supply chain. Oil to the eighties and yet:

In all likelihood, there is some combination of these factors which has kept a serious lid on the global economy’s production side. The US goods frenzy has continued, and for that combination it just hasn’t trickled (let alone flooded) its way down to the opposite end of the goods.

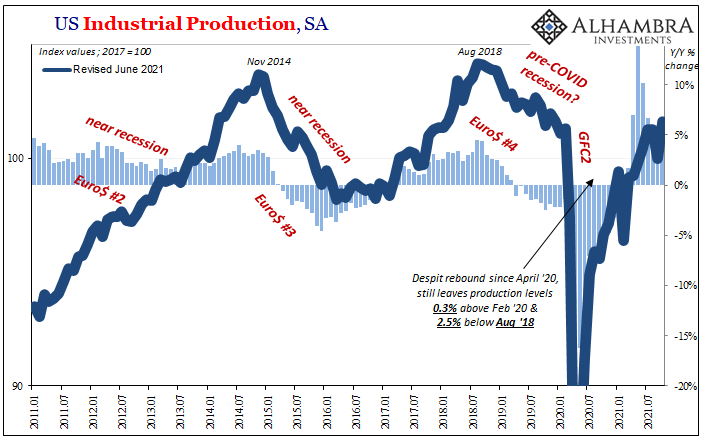

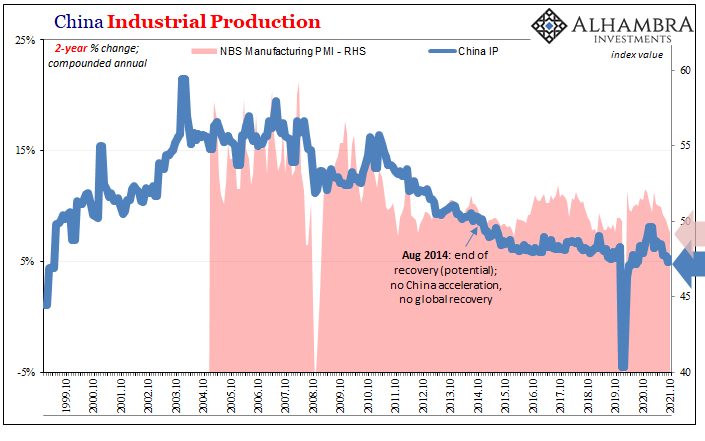

The best illustration of this might be US Industrial Production, among the better set of production numbers in the world right now – and they aren’t even good. It took until October 2021, the latest update, for overall output to just equal February 2020. And still production remains an astonishing 2.5% behind August 2018.

So, when we say something is suppressing industry that part is indisputable. What, exactly, is doing the suppressing, that’s open for interpretation. Shocking no one, I believe it much less (OK, nothing) labor shortage or supply squeezing and more recovery shortage due to uncertain future demand (including the very real possibility of an earlier early Christmas hangover) combined negatively with the unfavorable, upside-down pricing structure.

It might make a whole lot more sense to run operations as lean as possible until the economy gets over this hump of artificiality with these so many imbalances. And if you’re leaning more pessimistic already about “then what”, so much the better to stay lean and cautious.

Stay In Touch