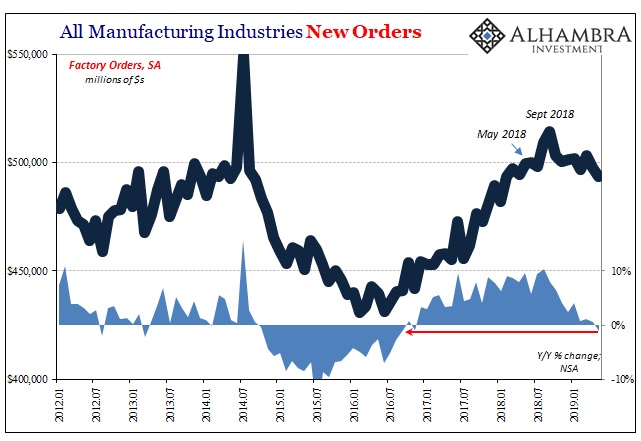

The US manufacturing sector may not be in as bad a shape as its German or Japanese counterparts, though it appears to be catching up on the downside. The Census Bureau reports today that new orders for all types of goods in all industries fell 1.6% year-over-year (unadjusted) in May 2019.

This was the first minus sign for the broad category which includes both durable and non-durable goods manufacturing. Orders hadn’t fallen on annual basis since 2016.

It is further evidence that the supply chain is being forced to adjust to the inventory pile up from the end of last year. Despite the unemployment rate, the slowdown in consumer spending has persisted. With inventory levels running too high, retailers and wholesalers are starting to order less new product while they try to work through what’s already on hand (but wasn’t expected to be).

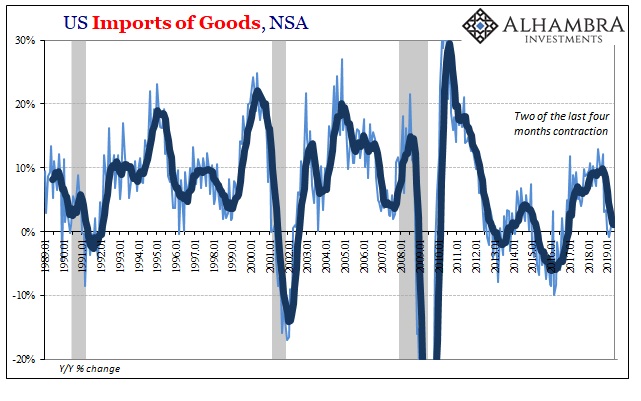

This imbalance isn’t just a concern for US suppliers and producers. If domestic sellers are ordering fewer goods from American manufacturers they are also going to be ordering and importing fewer goods from foreign competitors.

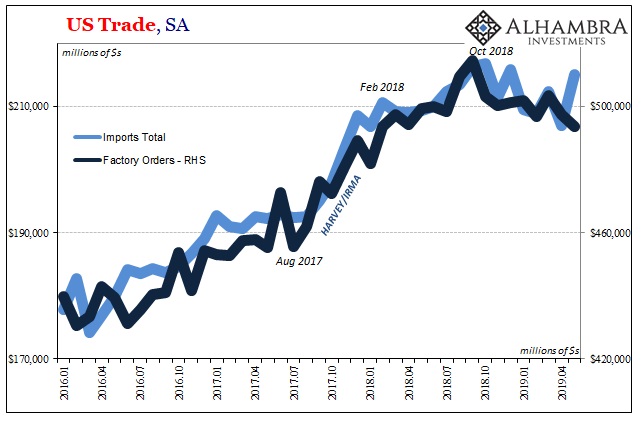

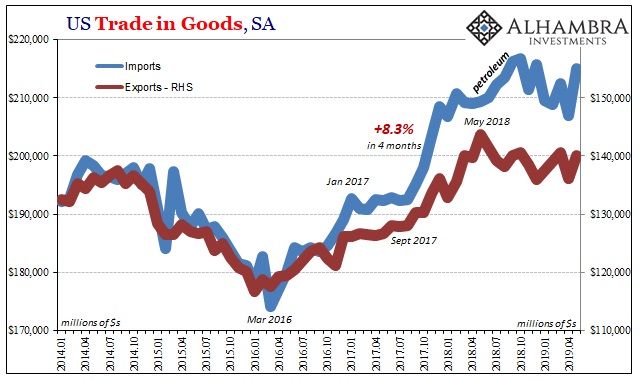

The Census Bureau also reported today on estimates for US trade. In the import category, seasonally-adjusted imports rebounded in May but remain lower since late last year. Despite what may be one-off factors in the short run (trade wars) import activity has closely resembled factory orders.

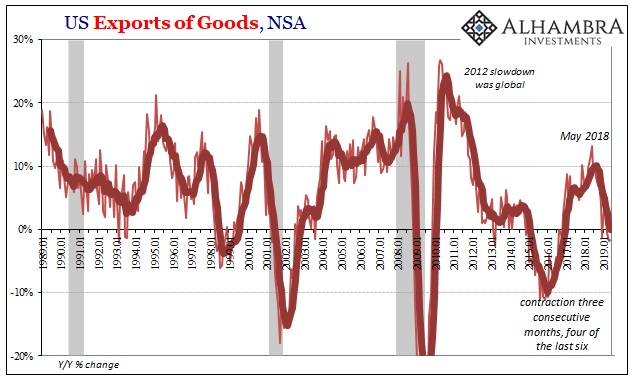

Part of the weakness in US production is due to flagging global trade. Foreign demand for US goods has turned negative, too. US exports in the month of May were down 1.6% from a year earlier. It was the third consecutive month of year-over-year declines. Unadjusted, US imports were up just 2%.

The difference between imports and exports is timing. US demand for foreign goods is more closely aligned with the landmine, the October-December thumping across global markets. Exports had begun to tail off several months earlier, coinciding with the first eruption in the global monetary system (May 29).

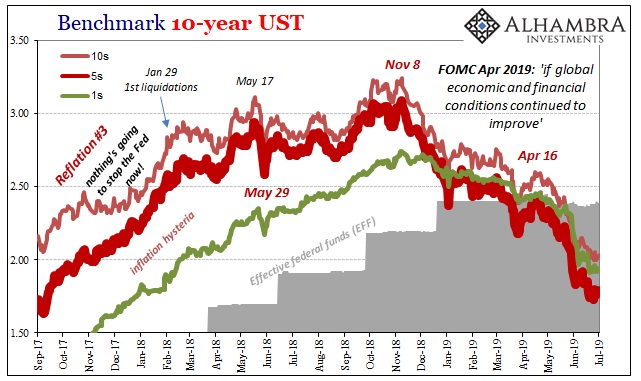

It matches what we find in other data elsewhere; the global economy began to experience and display the negative eurodollar effects first, with the US economy following along the same way if a little later. That’s all “decoupling” ever was, mistaking variation in timing for something more meaningful. I wrote at the start of last August, months before the landmine:

And we can look past the resurrection of “decoupling”; as in the US is back to outperforming Europe and the rest of the world. At what point over the last ten years has “decoupling” ever held longer than the short run? Decoupling always becomes convergence, and never in the good way.

It was the same three years before during Euro$ #3:

Thus, 2018 decoupling really hasn’t been any different than 2015’s. The key is timing, in that eurodollar event #3 impacted overseas locations many months and even a year before spreading inward to produce a near-recession in the US.

If anything, the calendar difference this time around seems to have been closer together under Euro$ #4. Much of the world felt the first negative pressures around April and May (rising dollar, May 29) and then at most six or seven months later the global landmine which included the US economy in its damage path.

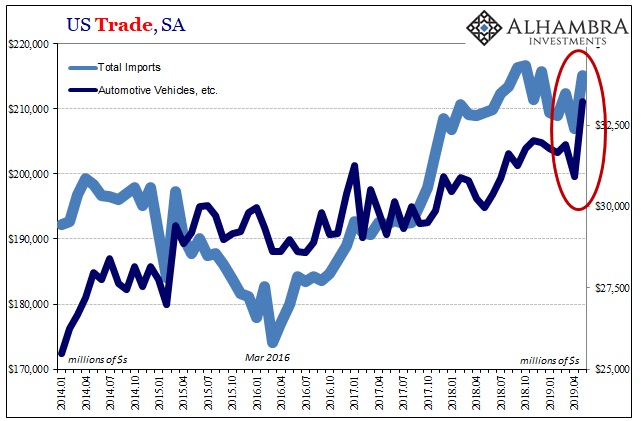

As for the specifics of May’s import increase, the majority of it was curiously due to a sudden rush of inbound automobiles.

Imports overall from both Europe and Mexico were up strongly in that month – compared to a continuing double-digit decline in them from China. It may be trade wars on both counts; no doubt that’s why Chinese totals are way down, but also it could be carmakers channel stuffing in case specifically auto tariffs are eventually enacted elsewhere.

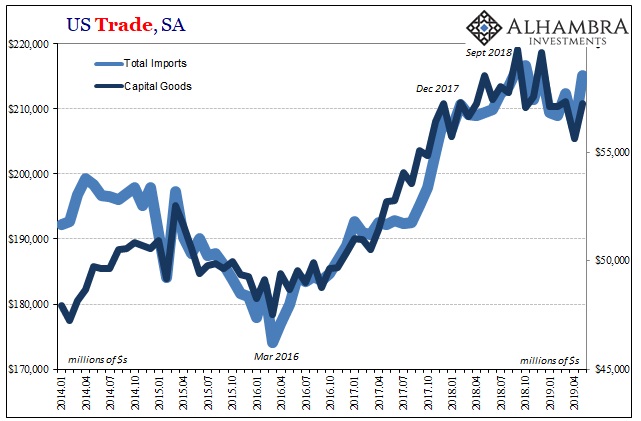

The other part of May’s import rise was capital goods. In this case, however, the direction and intensity beyond the latest monthly data point is displaying these other macro factors.

Total imports are down a little less than 1% since October while the value of imported capital goods is down more than 4% in the same timeframe. It was down 7% to April, an important sign of fundamental (supply side) economic expectations.

Five months into 2019, the data is harmonizing as the abrupt end of decoupling combined with continued weakness across the whole global economy starting in trade. It may sound like trade wars on the surface, certainly the timing fits with when the topic became a mainstream talking point. However, US tariffs on Chinese goods and even the threat of more on others just doesn’t add up.

Nor does it explain how this is nothing new. We’ve seen this exact behavior before when there was no trade war (though there was once talk of a currency war in 2012). It’s why the global bond market doesn’t care one bit about trade talks in going in either direction. The trade wars are in the data, but they are not responsible for the overall shape of it.

Stay In Touch