On August 12, 1985, Japan Airways flight 123 left Tokyo’s Haneda Airport on its way to a scheduled arrival in Osaka. Twelve minutes into the flight, the aircraft, a Boeing 747, suffered catastrophic failure when an aft pressure bulkhead burst. The airplane had been improperly repaired from a tailstrike (the tail of the aircraft actually hitting the runway pavement) seven years earlier, and therefore wasn’t sufficiently robust to maintain itself from the wear and tear of years compressing and decompressing the cabin.

Upon rupture, the 747’s passenger compartment rapidly decompressed which flung debris toward the rear of the aircraft. It severed all four aft hydraulic lines and even kicked loose the vertical stabilizer.

With the loss of these control surfaces, there was no way for the pilots to really fly the airplane. The jumbo jet, however, didn’t immediately plummet it stayed aloft another 32 minutes before crashing into Japan’s Mount Osutaka. It stands today as one of the world’s worst air disasters.

Though the pilots were unable to control the pitch, the aircraft itself maintained flight due to what’s called a phugoid cycle. This oscillation is an example of a natural negative feedback loop. When the nose pitched down for reasons beyond the pilots control, the 747 gained speed which increased the wind over the wings and therefore created more lift.

The nose then pitched back upward, only it then caused the jet to lose speed, therefore lift and then nose down all over again. The cycle could’ve repeated for a very long time, the airplane remaining in flight so long as there wasn’t any further damage or catastrophic input (like a mountain).

This sort of cycle is perfectly natural even observable in human behavior. Negative feedback loops are quite common, especially in finance and markets.

An example might be an illiquidity oscillation; liquidity dries up which exposes leveraged or weak hands, these are then forced to reduce their own exposures, which piles on further to negative pressures. After a while, though, enough positions are squared off that risk parity can be achieved, equilibrium re-established, and the wave crests over whatever market. It may even seem like everything has gone back to normal.

Except, it hasn’t. Unless whatever caused the “run” in the first place is extinguished or is met with some outside force, which might be the catastrophic purging of weak hands in firesales, the cycle is simply set up to repeat. If you look closely enough and in the right places, you can observe the process:

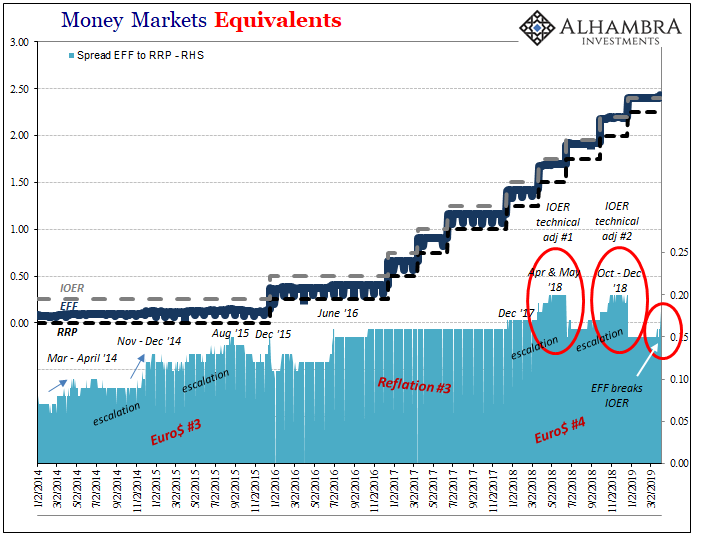

The EFF spread over RRP gives us a good sense of conditions adjusting out for nominal changes (“rate hikes”). The EFF spread oscillated during Euro$ #3 though it has been much clearer during Euro$ #4 so far. The reason for that is, ironically, the Federal Reserve.

By performing two “technical adjustments” to IOER, which haven’t really accomplished what policymakers were hoping, it has had the effect of backlighting the negative feedback loop in its progressions. There was the first major eruption in April and May last year, one which is corroborated by market charts as well as in economic statistics.

That sort of disappeared for several months during the summer, which led many to believe that it was all nothing more than curious fluctuations and the economic boom left undisturbed. Until, of course, another oscillation which struck in the October to December window. Like the first, it is corroborated by outer market behavior as well as economic accounts.

By January, rinse, repeat. The upside of the fluctuation has been interpreted again as if everything is over, nothing left to be concerned about. The Fed “fixed” what was wrong with its new dovish stance, joined by other central banks around the world.

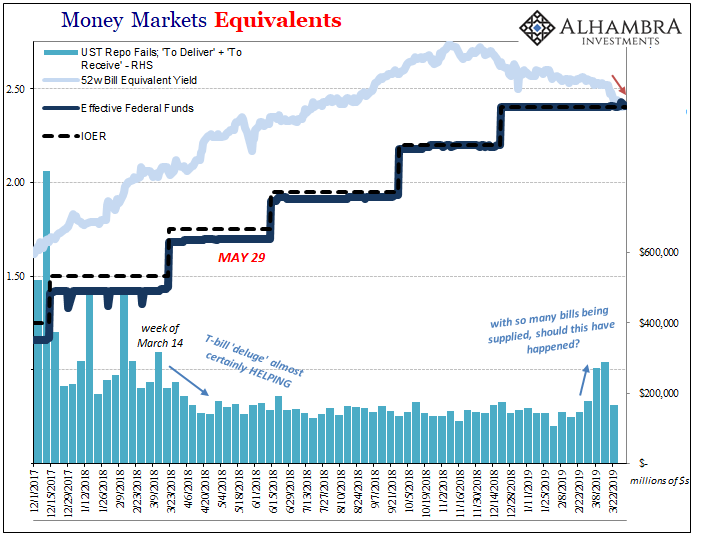

Only, as noted yesterday, we are starting to see the first signs of a third oscillation in the same sorts of place; those like the otherwise irrelevant federal funds market where the effective federal funds rate (EFF) jumped to as much as 3 bps above IOER last week at the end of Q1.

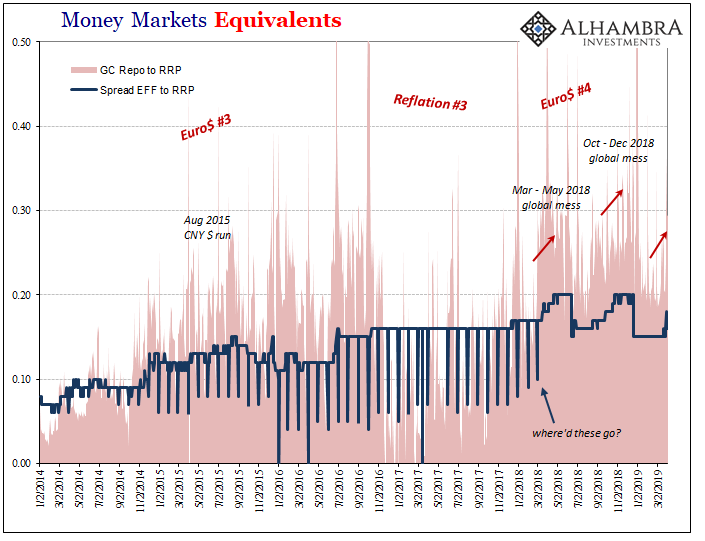

These cycles are also confirmed, importantly, by repo:

The latest one seems to have triggered a non-conformative response in collateral. For the first time in about a year, repo fails spiked. It wasn’t a big one, certainly nowhere near those that cropped up in late 2017 and early 2018, but given the baseline in T-bill supply it does get our attention.

What I mean by that is ever since December 2017’s tax reform, increased fiscal deficits have meant an increased supply of bills. These are, for the repo market anyway, top-notch stuff. Bills are all OTR and therefore a much greater supply of the best of the best collateral which adds more margin even to a funding system (domestically) operating in dysfunction.

So, we have to consider that what appears a minor increase in fails is perhaps by baseline comparison more trouble than it seems otherwise because of what has been a constant oversupply of bills. It was, of course, during those same several weeks when bond rates all over the world dropped far and fast.

And now we note what seems to be the next downswing in our US$ funding phugoid oscillation. It is a cycle within a cycle, this negative feedback operating inside Euro$ #4.

Nothing ever goes in a straight line. History itself is cyclical rather than linear. You can reduce almost every trend especially in markets and economy to repeating cycles. And because of this, it allows for these periods when even though things are going wrong it doesn’t immediately seem that way on the surface. Until, unexpectedly, right back in the quagmire.

What we are all hoping for in cases like these is that something meaningful occurs (exogenous input) which breaks the cycle. In between May and October last year, it was supposed to have been wage growth (the highest in a decade!). Right now, it’s dovish policies. And yet, the next oscillation looms.

As does the mountain.

Stay In Touch