To be an interested observer of things in the summer of 2013 was to be awash in the awareness of so many contradictions packed into one little piece of history. Forward guidance, for one, recognized the effects of markets. If QE was really effective, interest rates would rise not fall in anticipation of those positive effects.

This was, actually, the whole thing behind 2013’s “taper tantrum.” Ben Bernanke came up with a contrary scheme the year before when announcing QE3 hoping to head them off. He anticipated that his form of “forward guidance” would prove decisive; that is, the Fed’s Chairman promised QE3 would be “open ended” and therefore the central bank would keep on buying MBS (technically TBA) no matter.

The idea was that markets would be more enthralled by the purchases than their expected success; rising rates betting on the latter being held in check by lower rates due to the Fed’s persisting bid.

More than that, Economists had further expected that this “easing” would kickstart a strangely lethargic economic system. After all, if you need three QE’s “something” is already amiss.

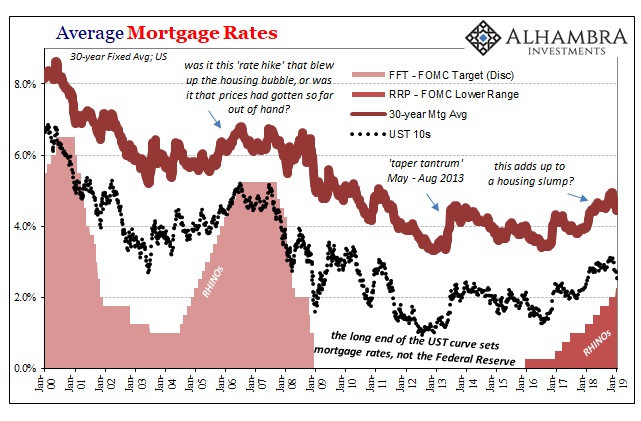

It all came to a head in May 2013. Bernanke, as I’ve noted before, never actually said the word “taper.” What that meant for the market was something else indeed; maybe QE3 (plus a fourth in UST’s) had worked, so like a cork held underwater interest rates exploded higher into what became Reflation #2.

Except, the economy hadn’t actually done much by way of accelerating. Even FOMC officials were still talking about “clogged transmission channels” and now we know one of them recognized QE’s monetary “head fake.”

The result was a toxic mix, one which confused and perplexed pretty much everyone for another year or so until the “rising dollar” of 2014 settled the matter once and for all. But along the way, more contradictions.

By early 2014, Wells Fargo, the nation’s largest mortgage lender, had laid off about 12% of its workforce in that financial space. The trigger was supposedly interest rates, according to mainstream convention, when the real killer was negative convexity.

The MBS market had been blown apart by the Summer 2013 Tantrum. Blame it on taper if you want, but the issue was, and remains, liquidity. Negative convexity, to oversimplify, is a fancy way of saying that your position gets larger the more any market price moves against you. If you are long some MBS derivative or protection (like interest rate swaps) and the price of MBS drops, if you aren’t careful the more the price drops the more long that price you can become.

Writing protection against a price drop becomes suicidal, especially since you aren’t actually running a matched book. Dealers stop writing protection at reasonable prices.

If you are a dealer who is betting on Ben Bernanke’s forward guidance (open ended QE3) and then the word “taper” is introduced, negative convexity isn’t just a textbook fear it transforms into devastating reality. And without actual economic growth to sustain the basis for the thesis, liquidity drops to nothing and for several days in May it became fire sale city.

Here’s what I wrote in July 2013 in the middle of tantrum:

As I mentioned a few days ago, if current GDP estimations are close, we will have seen five of the past six quarters at 2% or below (in some quarters much below). Without monetary policy opening a clear channel into real economy activity (not stock prices, there does not exist a “wealth effect” without widespread debt accumulation), household incomes cannot support rising rental rates that would mirror real estate prices.

In other words, since QE does not really work, the mini-housing bubble created in anticipation of it was limited by its own effects!

Wells Fargo wasn’t the only bank to notice the devastation in the TBA dollar rolls, it was just the biggest.

Fed officials had anticipated the one problem all along. They had expected real economic acceleration to cushion the blow. If mortgage rates start to rise even sharply for a little while, in an economy that is truly booming and recovering it might be a pain for some prospective home buyers but few others would even notice; banks especially.

These would shift mortgage personnel and balance sheet capacity from originating and underwriting subsidized (QE) mortgages to originating and underwriting consumer and business credit; dealers who were participating in the TBA market would shift money dealing activities to the plethora of opportunities a real recovery would provide an economy starved of it for half a decade by that point.

Bernanke never expected banks to just pull out. It was the perfect storm for 2014. Once dealers started reassessing their embedded convexity risks (or risk more broadly) in MBS, they began doing so in all their books – starting with China and EM’s.

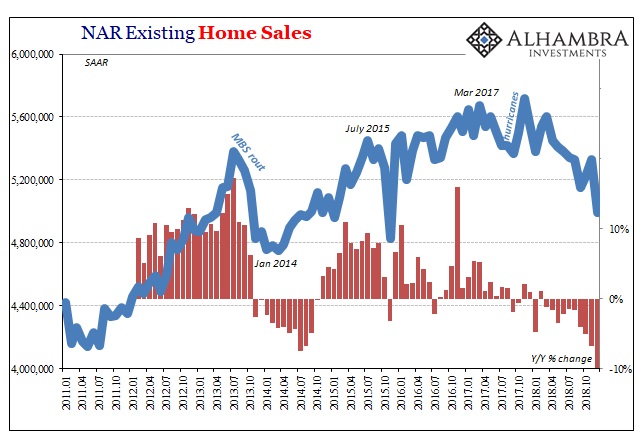

Despite what amounted to much bigger problems systemically, meaning global money, the US housing market quickly recovered. From August 2013 until about January 2014, real estate was pummeled. According to the National Association of Realtors (NAR), home resales dropped from a peak around 5.4 million (SAAR) to a low less than 4.8 million.

That five- to seven-month drop in the real estate market was chalked up to interest rates when it was the guts of money and liquidity instead. The ripples of negative convexity, not the third call for the end of the 30-year bond “bull market.”

The current housing slump is being blamed on interest rates, too. This one, though, is much deeper and longer lasting already. After peaking way back in March 2017, the resale market has been persistently if not directly lower for approaching two years now. The latest data from the NAR puts resales below 5 million (SAAR) in December for the first since November 2015.

Year-over-year, sales volume was down 10%, the largest annual contraction since the big housing bust nearly ten years ago. This is getting pretty bad.

Blaming interest rates is the lazy way. Something is different between 2013 and 2018, alright, but it’s not only negative convexity. TBA isn’t the problem this time, it’s the labor market. At least in 2013, the latter was positive and would get better in 2014 (if overstated by trend-cycle statistics, I believe).

The labor market in many ways has never come back from the 2015-16 downturn. That’s the difference. Weakness here has left the real estate market unable to collectively deal with relatively small changes in inputs, interest rates being only one of several. Uncertainty is the greater factor.

When you combine a soft labor market (no matter what the unemployment rate says) with growing unease about the economy, the end result is resales tanking the more 2018 draws on.

Housing isn’t really an important part of the economic picture, so it’s not as if the US economy is in danger of this slump bordering on a bust.

However, housing tells us something important about the real state of the economy through consumers. These negative factors are having an effect here, so it isn’t too much of a leap to suggest they are playing out in other parts of the economy where it does matter (consumer spending overall; though we will have to wait on the Census Bureau to come back from furlough before we get the data on retail sales and other categories of consumer activity and demand).

What happened in 2013 was a massive financial upheaval, and yet the housing market popped right back up. In domestic terms, there really hasn’t been anything like it in either 2017 or 2018, especially not in the mortgage market (TBA or otherwise). And yet, housing has suffered far more and for much longer this time than last time.

Something is different, alright. The economy is in worse shape now than in 2013. So much for four QE’s and a collapse in the unemployment rate.

Stay In Touch