The Federal Reserve wasn’t the only major central bank conducting open market operations (OMO’s) this week. On the other side of the Pacific, the People’s Bank of China (PBOC) had been, too. Big ones. And in both places, nobody really seems to know what to make of them even though they are actually connected to the same offshore dollar problem.

Increasingly illiquid markets and more active central banks. The latter doesn’t fix the former, it’s an advertisement.

How's it going in repo?

ICYMI, the Fed announced today a big increase in O/N caps to $125bln, and term operations upcoming will be up to $45bln.

You know, nothing to see here. Perfectly normal. Totally under control.https://t.co/71qaVnUuwc pic.twitter.com/Y6GBCqnQYD

— Jeffrey P. Snider (@JeffSnider_AIP) October 23, 2019

Given what the PBOC felt was necessary with its OMO intervention as well as what the central bank reported on its balance sheet for September 2019, there will almost certainly be more RRR cuts in the near future. It’s getting to the point again where there pretty much has to be.

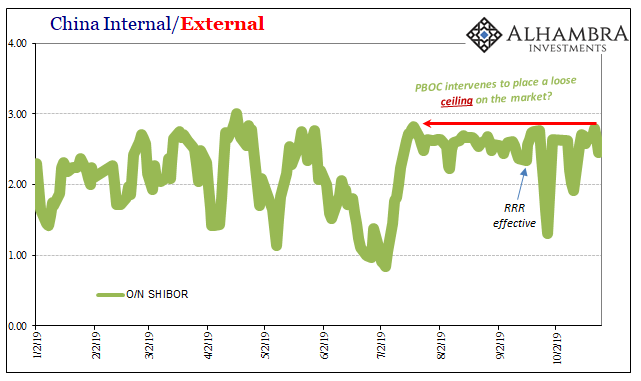

Let’s start with Overnight SHIBOR, the unsecured interbank or overdraft rate. This is a key part of China’s RMB money markets where surplus funding meets unexpected shortfalls. High or low rates here, it almost doesn’t matter which one so long as things are predictable and dependable. Penalty rates on careless overdrafts aren’t necessarily a bad thing, volatility is.

In this money market, there was no notice of September’s broad-based RRR cuts (applied to big, medium, and small banks alike). Like it never happened. Outside of a two-day dump at the end of the quarter, in October the rate sprang right back up toward and near what sure seems to be a soft policy ceiling.

On Tuesday, O/N SHIBOR fixed at just less than 2.80% which was the highest since late July when this quirky sideways action showed up.

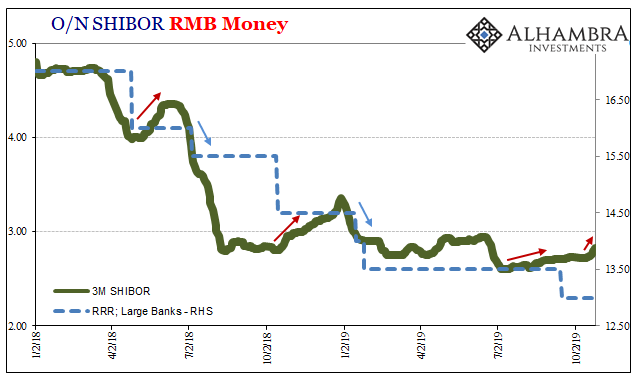

If that wasn’t enough to push China’s monetary authorities into OMO-land, then what’s been developing in 3-month SHIBOR probably sealed the deal. The PBOC can better manage longer-term unsecured lending with RRR’s, it’s the very short stuff where the mess develops.

As you can see above, however, there are times when even term SHIBOR doesn’t quite behave (noted by the red arrows). Whenever that has happened it then has triggered the next RRR in the series.

The last one in September 2019 doesn’t show up in 3-month SHIBOR, either. Like the overnight rate, the SHIBOR market as a whole doesn’t seem to have gained any additional spare liquidity from any banks that were given more freedom to use spare reserves reclassified under the low RRR as “excess.”

It happened last October, too, when the Chinese central bank reduced the reserve requirement by a 100 bps and 3-month SHIBOR instead rose substantially – the landmine. Chinese banks then were clearly hoarding, leading to a two-fer RRR by January.

It’s starting to feel that way in RMB markets this year, too. Therefore, unusual and unusually large RMB OMO’s this week.

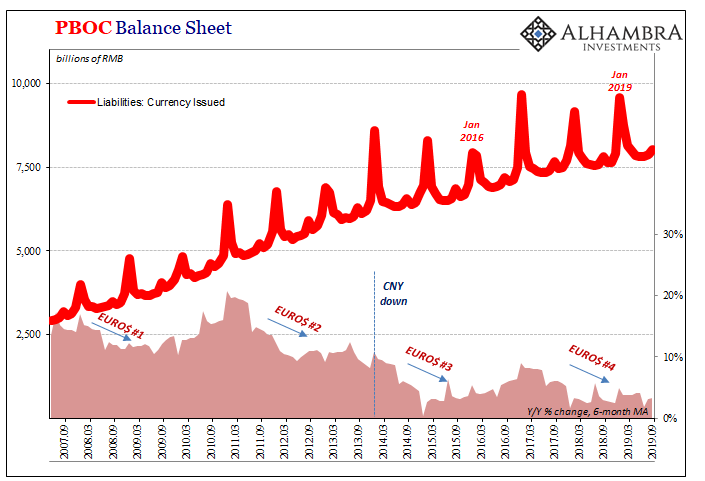

Going back several months, the PBOC has been more active in other ways, but again to little avail. Using other liquidity windows and techniques (all captured on the above line item), Chinese officials have apparently changed their collectivist minds about the need for more pro-active RMB management.

And the reason for that, the reason for all of this, remains the same. China has the world’s biggest dollar problem.

It’s an external shortage that becomes an internal squeeze by the accident of its design. No one had ever conceived that the global dollar system would come to this. Even in the aftermath of the Global Financial Crisis it was widely believed, inside the country, too, that even if the US and European economies would be affected by these deep monetary problems China and the EM’s would remain sheltered if not impregnable.

That’s what made Euro$ #3 so devastating in those places; the realization how that wasn’t true, either. No one wins. It just takes time for everyone to figure that out.

The dollar shortage in many respects never really ended after #3. There was reflation, of course, but not all that much where the eurodollar system had been concerned. Right where it mattered the most, globally synchronized growth was the smallest and least significant. At best, attempted redistribution (hello, Hong Kong) rather than actual expansion.

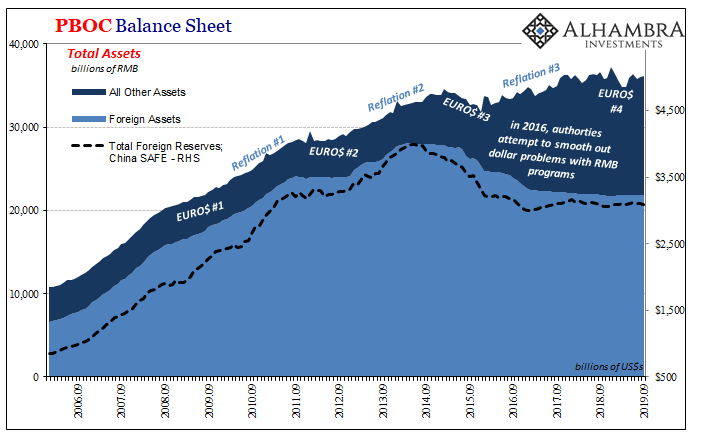

If there is a difference between #3 and #4 it is how China has responded during this later one. Four years ago, they read the modern neo-Keynesian textbook and followed it to the letter. After 1998 and the Asian flu, or Asian Financial Crisis which was really Euro$ 0.1, every Economist said that you build up a massive stockpile of foreign reserves so that you have insurance against the next possible Euro$ squeeze/shortage.

China, as the big beneficiary of eurodollar “hot money” inflows, amassed history’s largest. When the winds of risk began changing around 2013 as the entire global system re-assessed the monetary circumstances of EM’s including China, in 2014 as CNY started its fall (dollar shortage = rising dollar) the country’s authorities responded as they were directed in the textbook: they “sold” their reserves and utilized them.

It was a disaster. And it was that way because the textbook has it all wrong (you can read a more detailed description and analysis of the continuing string of consequences here and here).

With Euro$ #4, quite obviously the political regime doesn’t appear interested in selling reserve assets or using them however in the same ways this time. That would place more emphasis on less forthright schemes, perhaps quite a lot more “contingent liabilities.”

Except, there really is no avoiding the math here. Because there are no “dollar” inflows, the dollar shortage keeps on, there can be no space created on the PBOC’s asset side. During the best months where the PBOC is more active in the MLF or maybe OMO’s, the central bank’s total balance sheet only manages to remain stable.

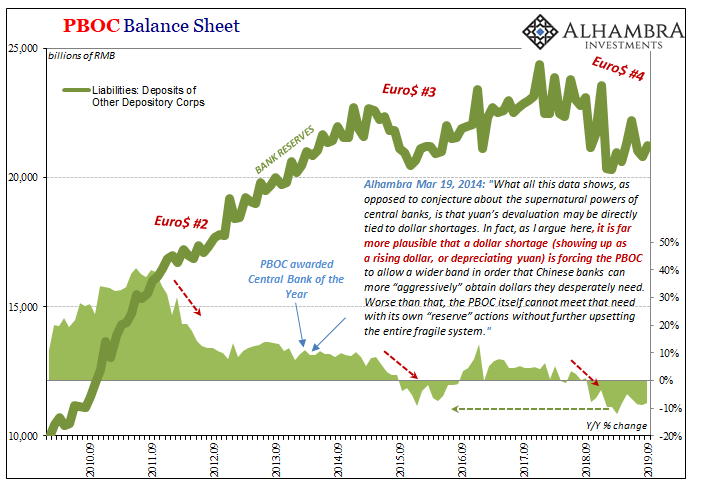

But even that requires shrinking liabilities (quirks of central bank accounting, as well as the government’s preferred position of how much cash it will hold at any given time). In September, the level of bank reserves once again declined by more than 8% year-over-year. It partly explains why SHIBOR didn’t respond to the RRR in the same month (risk aversion likely explains the other part).

In terms of physical RMB currency issued, the year-over-year growth rate (FOR CHINA!) last month was a paltry 2.7%. That was among the lowest on record following what had been what seemed like a concerted effort to get currency growth up a little bit more (though only managing at best 4%).

All of that in advance of a Golden Week holiday which can be tricky as far as liquidity is concerned.

In the US, the Federal Reserve continues to focus the public’s attention on bank reserves which don’t matter in lieu of understanding and appreciating the offshore, credit-based dollar zoo that does. In China, the PBOC can’t do anything about its bank reserves which actually do matter because of the same problem. Focused each on their own for very different reasons, no one tends to the zoo.

Stay In Touch