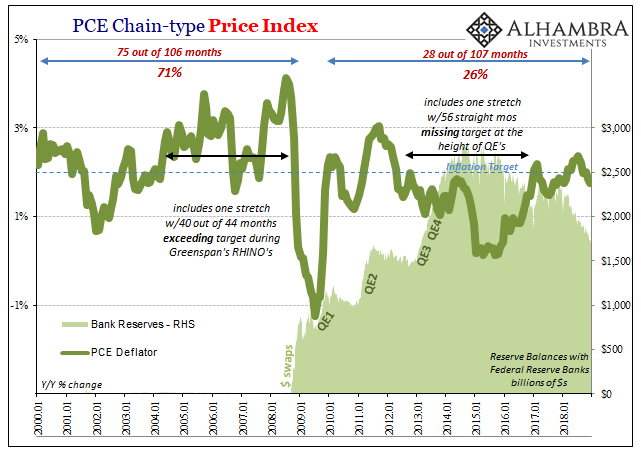

QT. Bank reserves. Balance sheet normalization. They really are going through all the motions in 2019. It’s as if officials can sense something just isn’t quite right. This would amount to a serious setback, of course, having assured the public repeatedly how the financial system has been remade into “resilient.” Janet Yellen, call your current office, Jay Powell’s Federal Reserve isn’t quite so sure any more about that whole bank crisis thing you said.

It’s hard to gauge whether it is mainstream thought that is evolving, or merely the form of its continued stupidity. Nothing ever stands still in this world, but that doesn’t always represent progress.

The Federal Reserve’s Vice Chairman for Supervision is Randall Quarles. He also chairs the Financial Stability Board. Both are resume-padding devices, filling out required requirements about pedigree. Thus, his opinions on monetary matters are given great consideration regardless of their content.

Recently, speaking at a monetary policy forum, he made what sounds like a very odd claim:

Occasionally we hear that banks feel they are under supervisory pressure to satisfy their [high-quality liquid assets] with reserves rather than Treasury securities…. that’s not the case… I don’t think we should have an official preference for reserves.

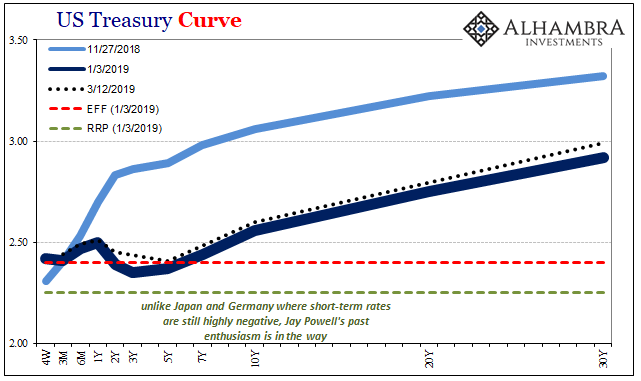

What he’s really trying to say is that bankers are telling him, and presumably FRBNY, that they are worried about the level of bank reserves. The Fed is reducing that level as it winds down its four prior QE’s. As assets runoff the asset side of its balance sheet, unless something offsetting is done the remainder on the liability side, bank reserves, must fall by an equal amount.

In official training, a bank reserve equates to what Milton Friedman once called “high powered money.” It’s hard to make that argument today simply because no one, outside of a bank comptroller, has ever seen one. You can’t walk into a grocery store and walk out again with food in your hands leaving behind only bank reserves. They’d call that stealing, maybe counterfeiting, too.

It is, quite simply, an accounting entry. It is one form of liability which banks may use to “fund” their balance sheet activities. That’s it.

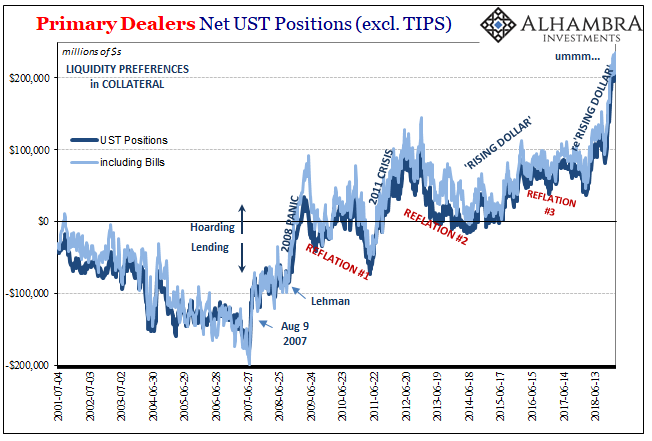

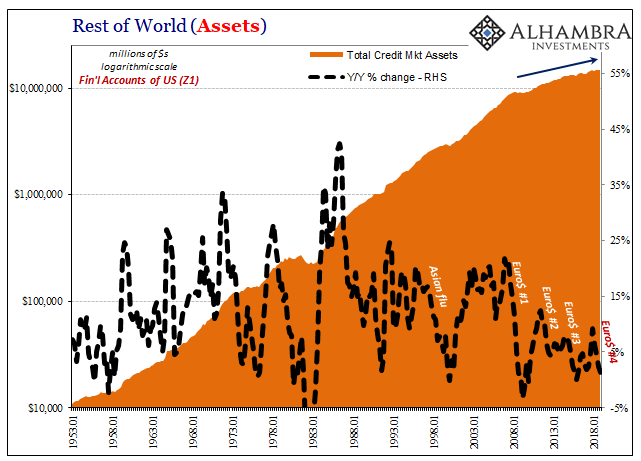

There were practically no bank reserves before the depths of the 2008 crisis; the US dollar system quite literally didn’t need them. This global eurodollar design redesigned what counted for “reserves.” Practically any bank liability will suffice, which is why there is such a demand for what banks can, but no longer want to, create.

These other forms of reserves were imaginative and dynamic, compared to the stale inertness of what central banks deliver almost by accident. QE’s were meant to play upon expectations, that was their big purpose. In terms of operative money, at best an asset swap.

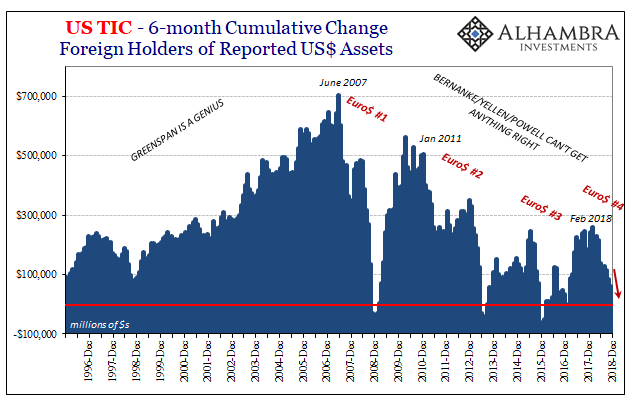

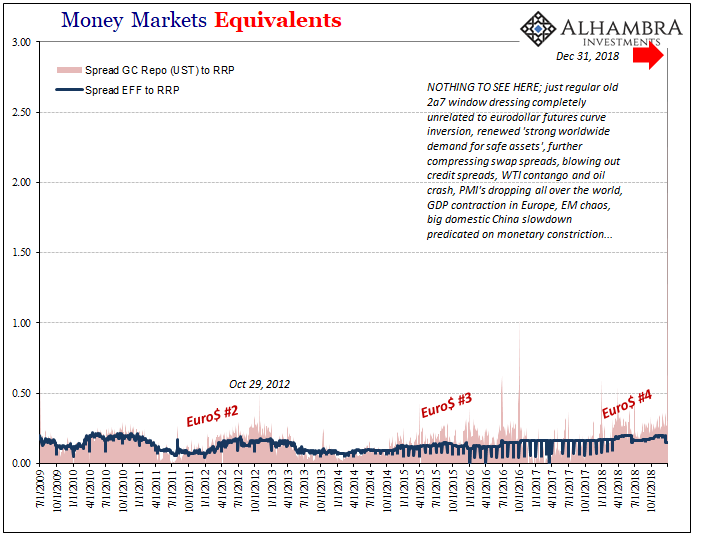

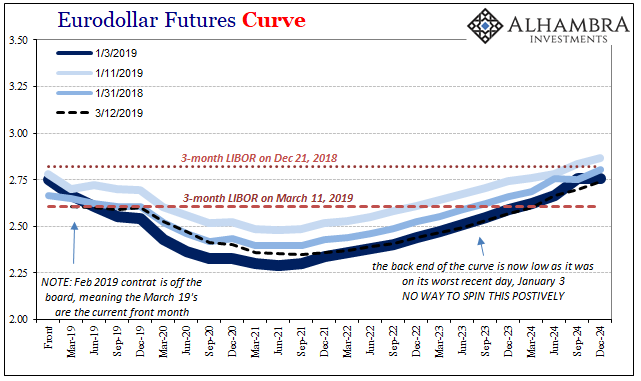

But that’s no longer how officials want to play this. They can’t because, again, something just isn’t quite right. There is palpable monetary tightness in the US dollar system that not even these boom guys at the Fed can deny.

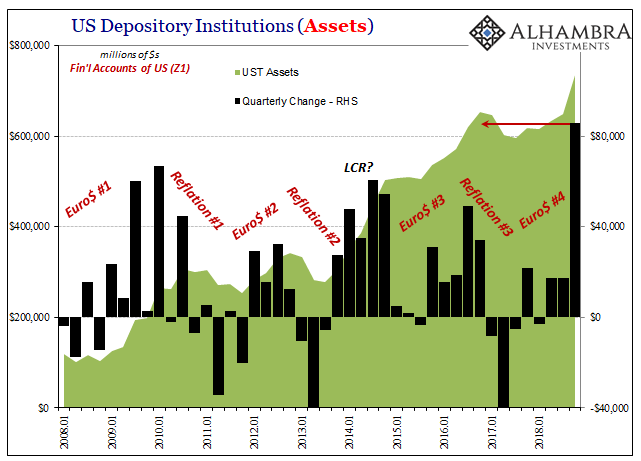

It must be regulations, then. Basel III, among other showy things, required banks to submit to what amounts to a modern stab at a reserve requirement – this LCR, or liquidity coverage ratio. To satisfy the LCR, the big banks must hold, unencumbered, a sufficient stock of HQLA, or high quality liquid assets. The LCR itself works like a capital ratio, a flashy amalgam of byzantine calculations compiled in such a way that you never actually think or ask questions about them.

It looks solid. Before 2008, people said the same thing about capital ratios and risk-weighted assets. But I digress too much.

The purpose behind HQLA is quite simple in theory; if you hold a lot of non-toxic waste assets then when the funding markets seize up again like they did in the worst parts of 2008 you can survive anyway. The LCR begins with a 30-day extreme stress scenario; meaning, how much in HQLA you will have to have on hand to go 30 days without ST funding.

But to do that, you will quite naturally have to liquidate those HQLA securities during the stress period. Thus, the emphasis and exhaustive definitions for what counts as “high quality.” In short, securities that won’t move much in value (or go up, as UST’s; small wonder why banks like holding them during times of unacknowledged turmoil) when the world is falling apart. You’d think there wouldn’t be any MBS or the like allowed here given what happened ten years ago, but I digress again.

Here’s where they’re starting to get hung up: if I have to liquidate, say, billions upon billions of my UST’s it stands to reason you will have to liquidate, say, billions upon billions of your UST’s, and the guy over in the corner will have to do the same thing as well as the lady in Hong Kong on the phone with the fella in Zurich. If we all have to liquidate at the exact same moment, who is going to buy them all? More to the point, what will they use?

To Federal Reserve officials like Randall Quarles who think about things this way, the answer is only Randall Quarles. And if the Fed is the only buyer in town, they are going to need a lot more reserves to be able to do this.

What the Vice Chairman is trying to say, then, by claiming banks are worried about preferring reserves over UST’s is that they are nervous about the current level of reserves as insufficient for all scenarios, even less-than-adverse ones. According to him, they’ve been forced into choosing bank reserves (conveniently explaining QT). Somehow, though, despite this presumed preference for what the Fed offers, banks haven’t been able to buy UST’s (or lease them) fast enough.

This is like thinking about rebuilding your car’s engine from a manufacturer’s manual you downloaded off the internet because you ran out of gas on the highway once, and now the tank is back down close to “E” again and you’re getting worried.

What policymakers are now thinking, and Bloomberg confirms that they’ve already surveyed the primary dealers on this very topic, is to set up a standing repo facility. To policymakers, this would mean no nervousness on the part of banks because with a standing repo facility they could liquidate their HQLA right at the Fed window in exchange for, you guessed it, bank reserves!

The level of reserves would therefore be adjusted based upon market demand for them. Problem solved! Nobody nervous today, tomorrow, or ever. Bonus: the repo rate should therefore behave much more predictably as a side effect (exactly how this is supposed to work, that’s another day’s digression).

The more astute among you will already notice that the net result of this scheme is, essentially, the very same as QE. Banks will still be swapping assets, only this time HQLA rather than “toxic waste”, for a higher reserve balance on account with FRBNY. The key difference, supposedly, is that the market is determining when and by how much the level of bank reserves will change.

For those who remember 2011, in August that year the FOMC debated bailing out the repo market. Well, almost eight years later here they are finally getting around to doing just that. You would think people would be asking why. Bill English, the FOMC’s Secretary as well as an Economist, summed this up very well on the emergency conference call held August 1. One point six trillion of reserves, apparently, wasn’t excessive after all:

MR. ENGLISH. With the funds rate up only a few basis points over the same period, a natural question is whether the repo rate has idiosyncratically diverged from the overall constellation of money market rates or whether it is a symptom of broad dislocations in money markets that could interfere with the transmission of the Committee’s intended monetary policy stance.

It’s difficult to parse as a layperson, of which I am one, but what he was saying here could not possibly have been overstated: either the repo market is just being kind of wacky, or the whole damn system might be broken, including how the central bank really fits into it (meaning, not really well if at all). Nothing to worry about; or everything is wrong. If they are still debating a repo rescue in 2019, that strongly proposes which one it really was.

The Fed, as is its standard practice, chose instead to split the difference – hoping that nothing was really wrong while remaining ready to act should that hope be misplaced. It was. In September 2012, in its infinite wisdom, the FOMC voted for, get ready, another increase in the level of bank reserves; QE’s three then four in December 2012.

The thinking behind the latter two QE’s was that by flooding the world with so many reserves, far more than the first two, printing money as many believed, there would always be more than enough. So, it’s a little hard to reconcile that view with 2018/19 being back to thinking about not enough again after a small rundown of the balance sheet. It’s like there is no amount of bank reserves that is enough.

This exchange from the same August 1, 2011, conference call helps explain:

MR. FISHER. I just want to get oriented here. I’ve been out of the country for a little bit, but when we last met as a Federal Open Market Committee, I think excess reserves were running around $900 billion—am I correct that they’re currently running about $1.24 trillion? Does anybody, Brian or anybody else, have a sense of those numbers?

MR. ENGLISH. Excess reserves are about $1.6 trillion, I believe, and they were at the time of the last meeting as well.

MR. FISHER. So we haven’t seen it all run into excess reserves then. That’s the point. There’s not much of a change.

MR. ENGLISH. Well, as Brian noted earlier, our operations determine the amount of reserves. So once we completed our purchase program at the end of June, reserves were whatever they were, and since then reserves have moved around, but they have not increased.

Mr. Fisher is, of course, the Dallas Fed’s Richard Fisher who shall hereafter be known only as the monetary head fake guy. He demonstrates here that he actually doesn’t know how bank reserves work, so no surprise he was faked out by them.

Which brings us all back to the real issue behind everything. The system didn’t need reserves before 2008, which is why voting members of the FOMC by 2011 really weren’t quite sure what they were or how they worked. Never mind trying to define exactly what was used as monetary alternatives during that period. Something, a lot of things were used that were not bank reserves.

Why doesn’t the post-2008 system just go back to using those same things? Why isn’t any private entity stepping in and providing an acceptable alternative, what with Janet Yellen’s claim to low risk and this economic boom? Why would anyone need the Fed to still, after a whole decade no less, get involved in any of this at all? The level of bank reserves was inarguably irrelevant prior, but now their level is a question of paramount importance? You see, something very big is missing, intellectually as well as functionally.

A standing repo facility, no matter how backwards you go to get to one, amounts to the same thing: it’s a monetary shortage that requires some serious thinking about fixing. What’s being offered, of course, isn’t actually any kind of solution so we are left instead to try and answer my original conundrum. Is this evolving mainstream thinking, inching just a little closer to the real problem, or is it evolving stupidity by going back to bank reserves for a fifth time?

They keep using bank reserves, only changing a parameter every time they do. Maybe stop it with bank reserves! At least, I suppose, in 2019 they’re no longer stressing 2018’s ridiculous excuses about T-bills and temporary “special factors.”

We’ve all been taught since Econ 101 that Open Market Operations determine everything, starting with the interest rate on money. There actually isn’t a single interest rate on money, for one, and as the repo market’s ongoing, eleven-year (and counting) plight keeps proving neither OMO’s nor POMO’s have much effect especially at certain times. It’s like there is a whole other independent monetary system that doesn’t work the way everyone seems to still think.

Maybe one day, if we are lucky, one enterprising honest official will go back and revisit Mr. English’s 2011 dichotomy and really absorbs what it would’ve meant, and could still mean.

Stay In Touch