What was the difference between Bear Stearns and Lehman Brothers? Well, for one thing Lehman’s failure wasn’t a singular event. In the heady days of September 2008, authorities working for any number of initialism agencies were busy trying to put out fires seemingly everywhere. Lehman had to compete with an AIG as well as a Wachovia, already preceded by a Fannie and a Freddie.

If Lehman was the personification of everything going wrong, Bear was its precursor where only the one thing seemingly did. In fact, throughout the middle of 2008 policymakers took great solace in what they thought they had achieved; sure, it was bad but only Bear went down, and even then it wasn’t a complete wipeout.

The summer of 2008 for offshore markets took on a very different reality, however. The panic was really two panics, the first finishing up around March 2008 merely the set up for its much more devastating second act (the events in early 2009 could reasonably be considered as the third). Whereas Federal Reserve and government officials took comfort in only the one, Lombard Street took stock.

Bear Stearns wasn’t some subprime peddler, Chairman Bernanke.

But if the opening drama was uncertainty about what was going on, the interlude between March 2008 and that September was deeper thinking about what perhaps waited for everyone in the end if it was to happen again (and to what unappreciated high probability it could). Market participants, it seemed, were willing to cut the official positive narrative some slack, maybe Bear was the worst of it, all the while still concerned that maybe it wasn’t.

It was a very short lease, a feeling public officials never truly understood. If things really did start to meaningfully improve, so be it; if they didn’t, the exits would never be large enough. That’s the point about this space between uncertainty and fear, almost a mini-reflation inside a downturn, everyone in the middle begins to worry about the exits no matter how wonderful that initial sigh of relief might feel.

The emotional appeal of the sell button (or collateral call) becomes paramount in the second part in a way it never would be in the first. Everyone might still be able to function with care and consideration, deliberate even when they are worried; fear throws all that out the window. If someone punches you in the face out of nowhere, you might hold on and wait to figure out what it was and why. If they throw a second punch, there is no doubt there is only “fight or flight.”

These things always come in at least the two parts. The “rising dollar” period 2014-16 was actually two in which the dollar rose really only during the first one. The former announces serious problems and then the latter confirms the destructive tendencies. The reactions are pretty distinct nonetheless, a lot more violence and downturn when fear is in control.

What happens in the middle is re-evaluation. The more serious the initial blast the deeper the rethinking goes, such that if whatever is amiss isn’t truly handled it will become the only thing that matters for Part 2’s fright. If it comes back, I’m gone no matter what. This is the asymmetry of things, there are no gains here.

It is therefore an opportunity as well as a warning. It would be, anyway, if authorities weren’t always too busy being behind. Policymakers are so self-assured there is no warning that can wake them from their self-imposed illiteracy. Self-assessment in public doesn’t allow for the consideration of small failure in policy let alone the repeated big ones.

That’s why the economy is always strong and resilient in the middle only to suddenly turn out very wrong in a very “unexpected” way. In May and June 2008, the narrative was one of cautious optimism that the economy might miss a recession altogether. A number of further warnings should’ve dismissed the notion outright, warnings that were escalating still despite the dissipation of worry (seemingly) due to Bear’s handling.

Same in Spring 2015, the Fed on track to “raise rates” even though the rest of the world seemed to be captured by invisible monetary conflagration. Warnings proliferated while offshore markets reassessed the exits, a measurement carried out with greater urgency with Yellen’s head buried further in the sand astride Bernanke’s which still remained in that position after so many years.

In the middle, reassurance reassures no one. Central bankers think it their sole job to do only that. They have devolved into mindless cheerleaders when during these times of uncertainty markets demand hard truths and even harder answers. Even the most unaware intuitively understands that oil prices don’t crash during “strong” economies.

That’s the big thing about Part 1 – it announced already that something serious is wrong. Denying that fact demonstrates only denial.

So, when Part 2 swings back around for whatever reason(s), there are the cheerleaders doing what cheerleaders always do and exits that for Part 1 seem so awfully, dangerously small and narrow. Uncertainty morphs into fear at the drop of a hat.

And yet, even then a “drop of a hat” isn’t actually as quick as the cliché makes it out to be. These are all processes that come at us over a period of time, sometimes condensed in memory if almost never in fact. You can date the second part of 2008’s panic to a number of calendar placements, but there can be no doubt the latest was July 15. That’s two whole months before Lehman when LIBOR spreads remained so conspicuously abnormal.

Same with 2011 and 2015-16. You might look at the extreme events of May 2010 presaging the even more extremes of July and August 2011 in the same way the last six months of 2015 were foretold by the last six months of 2014. At least in November 2010 the Fed offered up a second QE, not that it did any good (which markets noticed).

For a long time now, we’ve been writing and chronicling “uncertainty.” Where is the dividing line between that and Part 2’s outbreak of fear? It’s hard to know in realtime especially when the issue is offshore money, these shadow eurodollars of dark leverage. We have a hard enough time trying to figure what’s (really) on one bank’s balance sheet let alone all of them collectively.

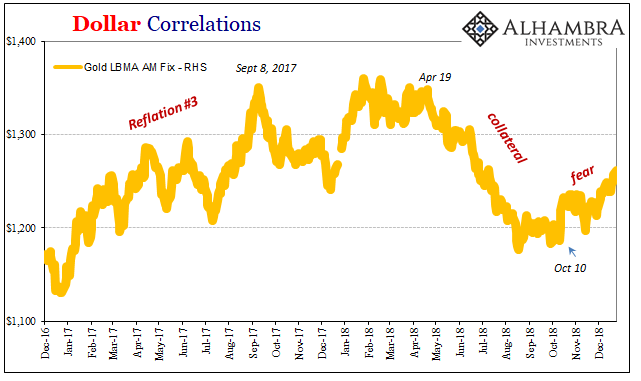

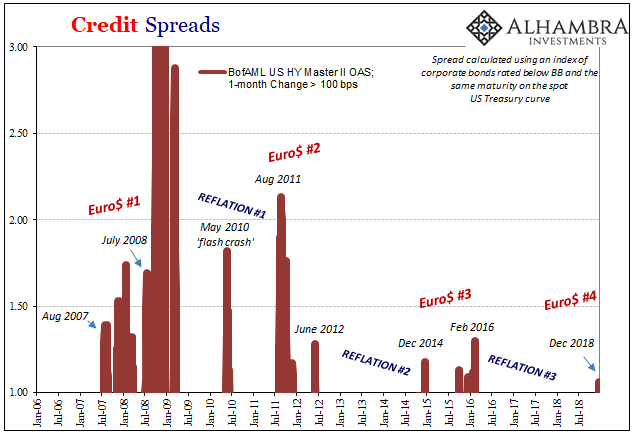

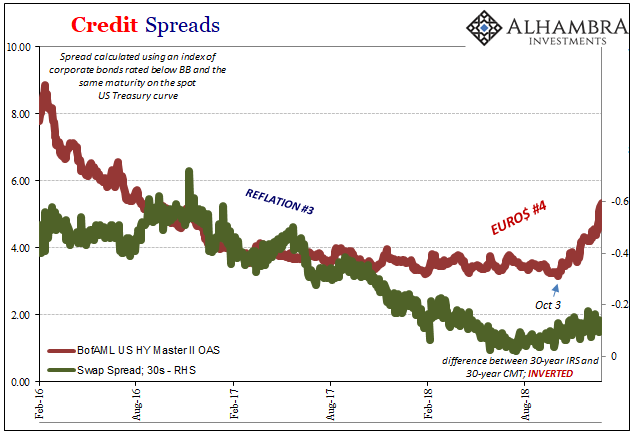

There are, though, a few indications of fear at the end of 2018. One is credit spreads, another is tied to them. Gold and Emerging Market junk bonds don’t seem bedfellows yet they are that and more. Gold keeps signaling rising fear as do now credit spreads.

It is highly unusual for spreads to blow out by 100 bps (in certain indices or comparisons) in a single month. That level of selling in such a relatively abbreviated calendar space is much more difficult to misinterpret. There are a number of technical and fundamental factors that can weigh on credit markets at any given time, but a short, sharp spread blowout of that magnitude isn’t going to be related to any of them.

Spreads then are about only the one thing – the exits.

As of Monday’s desperate selloff, the BofAML High Yield Master II spread blew out to a total of 106 bps for the preceding month of volatile trading. A bad month like this, as you can plainly see above, is plainly unusual and falls along with exactly the kind of bad associations economic as well as financial. There are no recoveries and economic booms during these, nor have they followed.

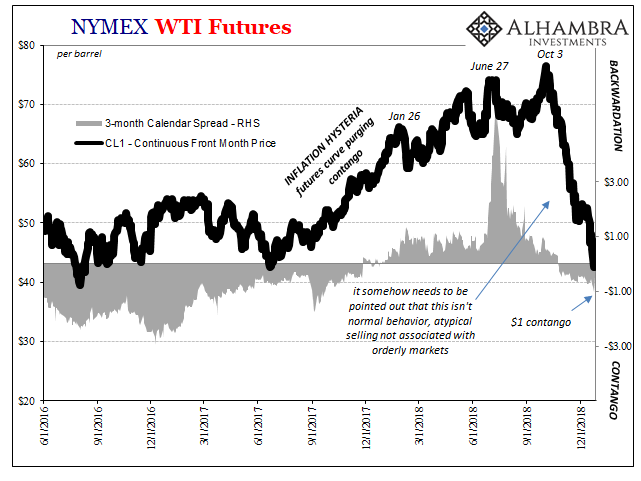

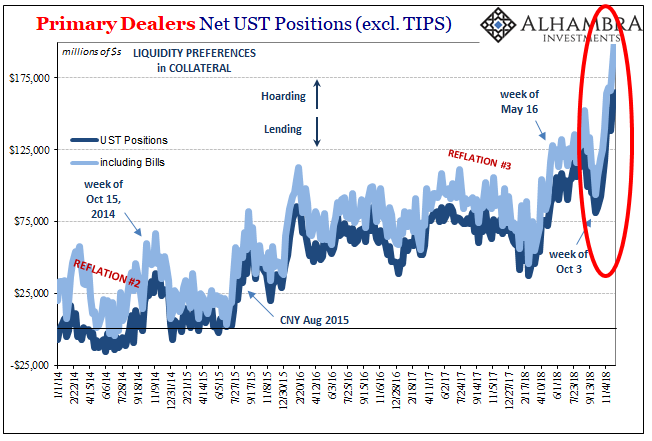

As with a whole bunch of other warnings, it all points back to the days immediately following October 3. Something changed; oil had fallen, for example, several times this year but none of those had triggered this systemically, uniformly negative response. Those earlier declines were watched with a wary eye full of caution and uncertainty, but this last one was met by outright fear.

For his part, Jay Powell had an opportunity to put out some of the fire, to keep unease from spreading into the disease of indiscriminate liquidation. He might’ve calmed markets (I personally doubt it) by talking about this “Fed pause” in mid-September, but remember he was intoxicated by the BLS figures, wage numbers most of all. Powell’s economy was never stronger than during this last middle, the weeks leading up to October 3.

The FOMC had all summer between the “strong worldwide demand for safe assets” and the first week in October to rethink things most of all this strong economy nonsense. There was everything wrong about May 29 (just as October 15, 2014, or May 6, 2010). Reasonable and rational human beings would’ve at least done that. Not policymakers, though, their ideology leads to nowhere other than the profession of cheerleading.

Why October 3? I have some thoughts on the subject, in more detail than those I’ve expressed before – including those I published on October 2. For now, it sure does seem like the only thing anyone is thinking about is the exits. That’s understandable, but I’d like to see everyone also think about why history rhymes so very closely. It has a lot to do with why another Part 2 always follows another Part 1.

The wasted opportunity of the middle.

Stay In Touch