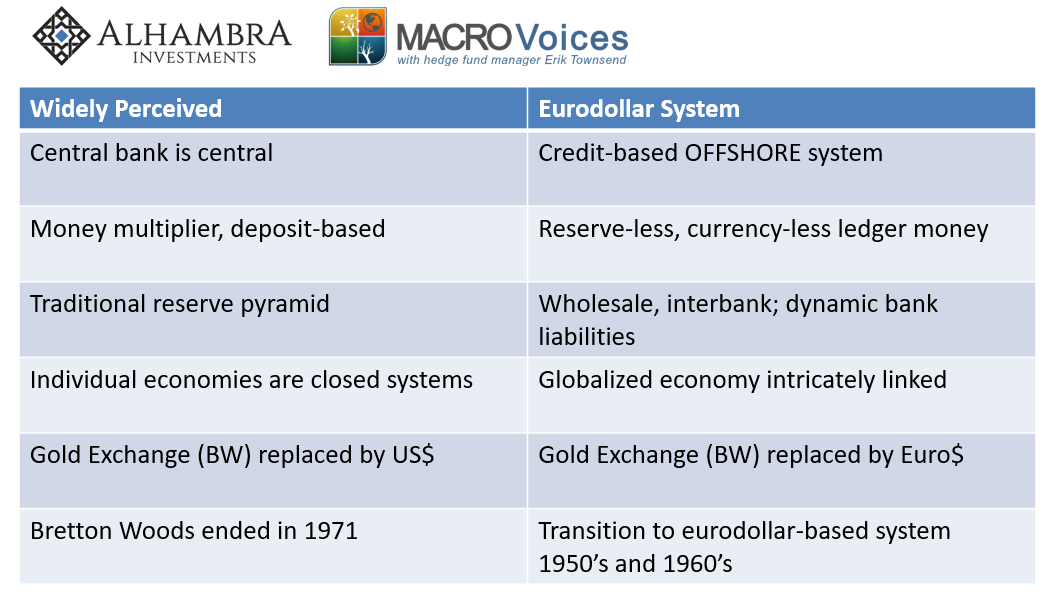

It’s the most testable of all hypothesis, yet the one which no one wants to test. The central bank is central. All the textbooks say it. You’ve been taught to believe it from your first introduction to Economics and finance. Whatever happens, you aren’t supposed to fight the Fed.

The US central bank unleashed powerful, novel liquidity programs, an ultra-loose response to growing crisis. Global panic happened anyway. Its officials assured full economic recovery from the genius of bond buying. It never came. The textbooks say the printing press towers over everything. Officials can’t even get fed funds right.

Time and again, explanations are crafted in such a way that the central bank remains central. It’s always, always something else. In 2015, they cried 2a7. In 2011, they blamed Portugal and Greece. In 2008, those damn subprime mortgages.

Some people are finally starting to notice federal funds. There is absolutely no legitimate reason why anyone should. The federal funds market is a non-entity, the pocket change of what’s leftover from the FHLB system in the aftermath of the housing bust. There’s really no one else there. It is the sparest of spare liquidity.

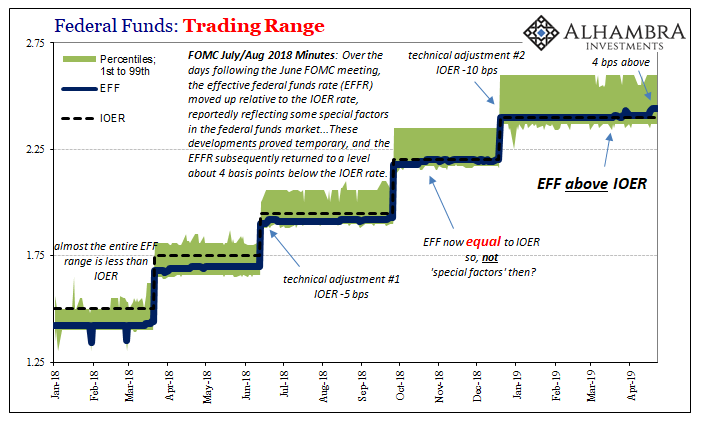

Somehow, though, it is in high demand. Over the last year or so, the effective rate for that market has moved up slowly. All sorts of ink has been spilled trying to justify the rise as nothing, or the benign consequence of prudent macroprudential impositions. It was T-bills or repo, maybe 2a7 still. How about Basel III’s re-interpreted nuance of page 246 of the NSFR?

Or money market funds.

As noted Monday, EFF broke 4 bps above IOER last week. A bps or two, apparently, you can ignore. Four is a spread too high. The usual suspects gather to decry tax refund season and government money market funds. It has to be something like that because if you consider the only logical alternative the entire worldview crumbles.

They really don’t know what they are doing.

This acknowledgement, a proper reading of all the facts and evidence, applies to the big things as well as small. How in the world can Jay Powell, like his three immediate predecessors, claim to nudge let alone control the economy when he can’t nudge let alone control federal funds?

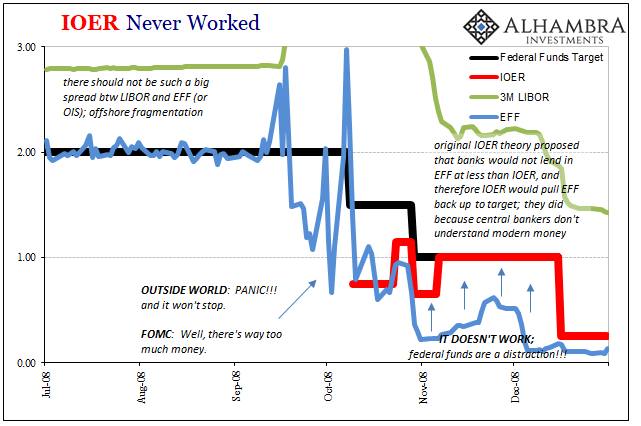

Officials even invented new schemes to make sure this would never happen. They did so originally as part of their crisis fiasco. IOER was introduced as a big deal – in theory. How big? Ask Bill Dudley in October 2008. As head of FRBNY’s Open Market Desk, where technical competence is meant to more than influence markets, Dudley wasn’t the least bit conflicted on the subject:

MR. DUDLEY. That’s why getting interest-on-reserves authority was very, very important. As Brian has said in earlier briefings, interest on reserves is going to start on Thursday, and that’s going to place a floor on the federal funds rate. So we think we’re in a situation where we have a very important tool that will allow us to expand the balance sheet but maintain control of the federal funds rate. [emphasis added]

The entire official apparatus was absolutely certain, from top level committee members including Chairman Bernanke all the way down the staff Economists, that IOER would put a floor under federal funds (at the time, EFF was way, way below the set policy target which no one would ever dare disobey, what with that whole printing press thingy).

Why?

In theory, they could not imagine a single reason for anyone to lend to unsecured counterparties at a rate less than what they could lend to the Federal Reserve. Park the excess liquidity as an excess “reserve” and get paid risk free by Bill Dudley’s desk. Absolute ironclad guarantee from the best and brightest monetary scholars.

They had no clue how this market was going. None. It would’ve been one thing to bungle about so badly in, say, 2005. But to do something like this in October 2008? Utterly, incomprehensibly inexcusable.

Very quietly, with no public acknowledgement, the Fed abandoned the concept but not IOER. If it didn’t function at all like a floor, then they simply switched it up. It must be a ceiling!

Again, this was no trivial reclassification. As I also wrote on Monday, the FOMC purportedly studied their intended exit from all this crisis-era stuff for years. They began planning how it would go as early as 2011, before being distracted by Richard Fisher’s monetary head fake. The exit topic was picked up again in 2013 and 2014, tested extensively, too.

Officials knew they couldn’t bungle the exit because it would endanger that very thing. The reason there is so much focus on the behavior, or misbehavior, of something like federal funds is exactly what I write: if you don’t do the small stuff it leads to much bigger questions. And not just among the very few paying attention. It is a horrible day for US monetary officials when federal funds gets even the slightest media attention.

To avoid something like that ever happening again, a centerpiece of the exit strategy, the FOMC turned to…IOER. You can’t make this stuff up.

Having totally failed as a floor, why would it act like a ceiling? Because. They haven’t exactly explained their rationale. I don’t think they really have one, just more fingers crossed and prayers said.

It sort of goes like this: if money market rates rise near or even above IOER, this would incentivize money dealers or anyone with spare liquidity parked as excess reserves to pull them out of the Fed’s pocket and place them in these money markets. That would then, in theory, cause the money market rate in question to fall back to where it “should” be.

If you really want to pressure money market rates lower, reduce IOER (technical adjustment) to amplify the incentive to use those excess reserves. This is what the July/August 2018 meeting minutes was referring to; supposedly “special factors” that technical adjustment #1, they really believed, skillfully and successfully handled.

Are you surprised it hasn’t worked? All the so-called experts are stunned. And they keep looking for answers in every place but where the problem resides, where all the evidence points.

Today, they say money market funds. What about last month? Or last year? EFF has been pretty consistent in its trajectory. This isn’t a new thing. It has been coming for a very long time, as if there is this stubborn though obscured, shadowy structural problem behind it all. One that comes out every few years or so. It might even make the Wall Street Journal stand up and take notice of China’s very much related dollar problem (with a half decade lag, give or take).

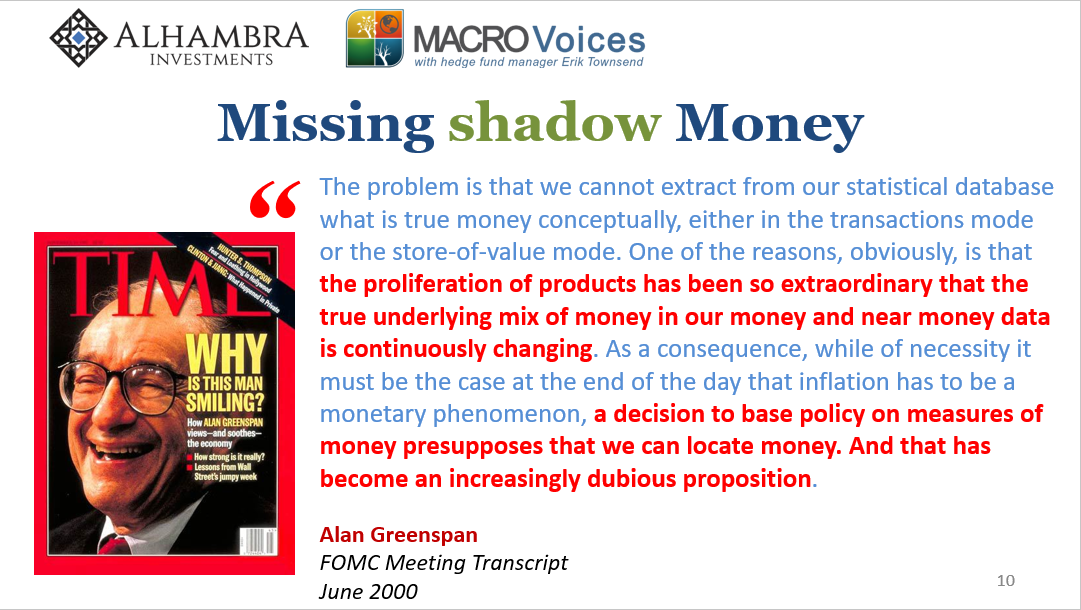

It can’t be that there is no money in monetary policy, that central bankers having long ago surrendered monetary competence in exchange for pop psychology have no idea how these markets really work. There is no way QE could have been a poorly designed puppet show. That’s not what we’ve been taught. It’s not what everyone says. Who needs history and evidence?

Stay In Touch